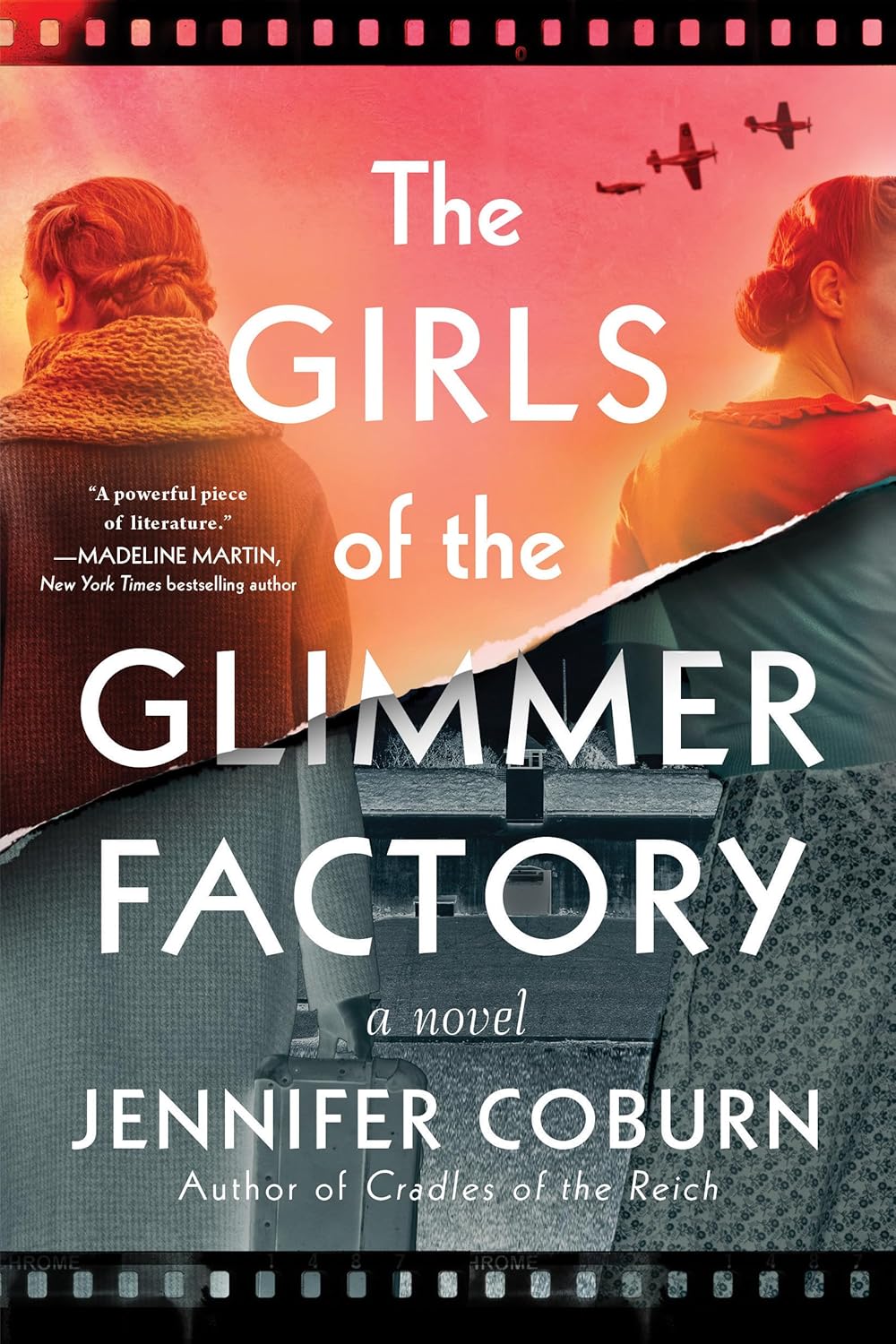

The Girls of the Glimmer Factory: A Novel

- By Jennifer Coburn

- Sourcebooks Landmark

- 480 pp.

- Reviewed by D.A. Spruzen

- January 24, 2025

A moving tale of loyalty, friendship, and the dangers of propaganda.

At the intimate level of the novel, author Jennifer Coburn shows how insidious propaganda can blame a country’s ills on convenient scapegoats and thus persuade citizens to accept unspeakable brutality. In The Girls of the Glimmer Factory, she explores for the second time in fiction the personal trials and sacrifices of those ensnared in the madness of the Third Reich.

Just before the outbreak of World War II, Hannah and her Jewish family fled Berlin for the safety of Prague, but by 1940, they must flee the Nazis once more. They manage to buy papers to emigrate to Palestine, but when Hannah contracts smallpox, her grandfather Oskar opts to stay behind with her; they will leave as soon as she recovers.

But Hannah and Oskar end up imprisoned in Theresienstadt, a “model” camp — from the outside. But behind the concerts and utopian settings staged for the Red Cross, life is hell. Hannah is put to work copying the Torah, part of a Nazi plan to found a museum of Jewish artifacts portraying what they assume will eventually be an extinct race. When she finishes her task, she angles for a job in the “glimmer factory,” where young women work slicing the mica prized by the Luftwaffe for its use as electrical insulation. This work, which leaves glittering particles stuck to the workers, makes it less likely that the women will be transported to Auschwitz.

Hannah is principled and stalwart. Nonetheless, when she encounters the resistance, she initially balks at joining. But when they ask her to help smuggle babies out of the camp, she relents. Although the removals are devastating to the mothers, if the infants remain in Theresienstadt, they will die. Hannah experiences intense love and loss like all the prisoners but somehow endures alongside her irrepressibly optimistic grandfather.

On the other side of the Nazi divide, gentile Hilde married a German officer and moved to his mother’s farm while he was deployed. When she learns of his death, Hilde can’t wait to get away from rural chores and start a new life in Berlin. Opportunistic and shallow, she inveigles her way into a secretarial job in a department making propaganda movies, where she meets her second husband, Martin.

A staunch Hitler loyalist, Hilde will do anything to prove herself. She receives an assignment to help supervise the production of a film in Theresienstadt, where she crosses paths with Hannah, her best childhood friend. Hilde demands Hannah as her assistant — she knows the woman is better than other Jews, after all. Besides, Hannah can speak Czech, which Hilde can’t, even though she had claimed to. Hannah knows Hilde is a party member and remembers how Hilde’s family turned Hannah away from Hilde’s birthday party for being, supposedly, an unsuitable friend. But Hilde had no choice at the time.

Of the two, Hilde is the more interesting, albeit less likable, character. Despised by both her mother and mother-in-law, she craves recognition and admiration. She will do anything and step over anyone to achieve her aims. But when Martin tells her about the gas chambers at Auschwitz, she is appalled. Still, she attaches no blame to her Führer.

Martin appears at first to be a gentle fellow, but he turns out to be more than accepting of the genocide. When Hilde learns that nearly 7,500 inmates will be transported to Auschwitz once the film is completed, she offers to have papers forged for Hannah so that the Jew can become her maid. Martin is appalled by Hilde’s actions, and “tears began to stream down Hilde’s cheeks.” She is astonished that her husband doesn’t understand “that the truth could be different things,” that she could be loyal to the Reich but also to her friend.

“Truth could take alternate forms and be no less true,” she thinks. “Why couldn’t Martin see that?”

In keeping with such duality, the book alternates chapters between the two women, which draws a sharp contrast between the thoughts and experiences of the sketchy “true German” and the nobler “no-longer-German.” The blindness to truth versus the desperation of living the truth.

The book ends with an abrupt conclusion that this reviewer found jarring. A long epilogue follows to tie up loose ends, which was at once satisfying and exasperating. It’s a long book and had to be brought to a close at some point, but perhaps it was one chapter too soon. Still, The Girls of the Glimmer Factory is a fascinating and engaging novel by an author who does meticulous research and can tell a good story without getting bogged down in the details.

D.A. Spruzen is the author of the Sleuthing with Mortals series and The Blitz Business.