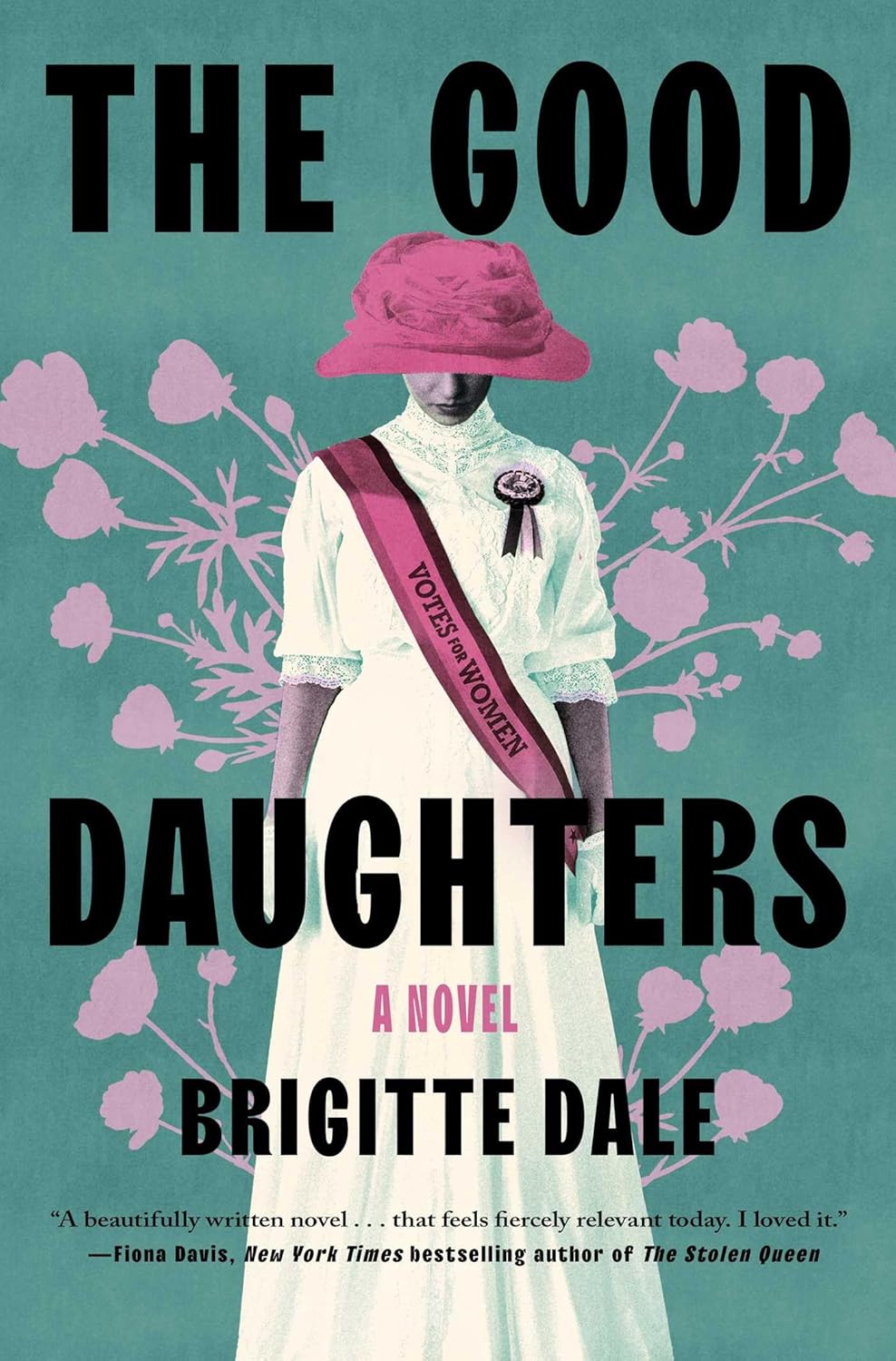

The Good Daughters: A Novel

- By Brigitte Dale

- Pegasus Books

- 352 pp.

- Reviewed by Madeleine de Visé

- January 2, 2026

This tale of 1910s British suffragettes feels uncomfortably timely.

Often, when I read a work of historical fiction, or really any work of history, I wonder: Why now? Plenty of books are published on the anniversary of their subject, which (to play the cynic) is a sure way to boost sales. Others bank on the novelty of fresh perspective or new information — in other words, something that reopens the conversation.

But there’s another way to ensure relevance — the best thing a story can be is timeless; the next best is relevant — and that’s to strike while the iron is hot. With that in mind, the next time you find yourself at Union Station in Washington, DC, calmly sidestep the National Guard patrolling the platform and grab a copy of Brigitte Dale’s The Good Daughters.

Set in London in 1912, the novel weaves a gripping tale out of the real-life Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the suffragettes who risked their lives to secure the right to vote. We meet Emily, the motherless working-class daughter of a prison warden; Beatrice, a blueblood law student who grew up riding horses on a grand estate; and the fiery, outspoken Charlotte, whose background falls somewhere in between.

When the story begins, Beatrice and Charlotte meet at a prestigious all-girls college, where they eschew tame, school-sanctioned suffragist lectures in favor of rousing town meetings led by suffragettes Isabel Hurston and her mother, Adeline. Beatrice, in fear of her domineering parents, pulls back from her activist pursuits after being reprimanded by the headmistress. Charlotte persists and is expelled.

Rather than return home to her disapproving parents, Charlotte throws herself into the arms of the WSPU, where she is welcomed by, among others, a young American woman named Sadie. Charlotte and Sadie keep busy with protests, pamphleteering, and quieter revolutionary tasks at Sadie’s family’s home — the de facto WSPU headquarters.

The first time the cops seize Charlotte for protesting, they throw her in Holloway Prison. There, she meets Emily through the bars. They forge a bond that nearly breaks when Charlotte suddenly decides to stop eating and drinking, a spontaneous act to protest her treatment as a common criminal rather than a political prisoner. On the brink of death, she is released early — and reports her success to the WSPU.

The suffragettes soon forge an alliance with Emily, warning her through coded messages of planned public protests that could lead to imprisonment and further hunger strikes. When Emily’s father, Holloway’s warden, grows weary of the jailed protestors’ tactics, he initiates — with the help of a truly loathsome doctor — the infamous forced feedings that were inflicted on several real-life suffragettes. (These are among the ghastliest scenes I’ve ever read in literature.)

These places, characters, and events comprise a condensed, dramatized version of the actual WSPU. In a postscript, the author draws parallels between her novel and its sources — the fictive Hurstons stand in for Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, for example — and clarifies her creative choices. The protests depicted in the book occur in one year (whereas the actual WSPU protests spanned several), and the novel is peopled with both real and imagined figures, all of them rendered beautifully.

When Beatrice visits Charlotte on a sort of extended bachelorette tour, something magical happens: she meets Sadie, bares her soul to her, and finds herself hard-pressed to leave. What follows is a loving, if secretive, affair: Beatrice and Sadie’s bond is life-affirming and infuses their grisly tale with hope, but it may not be enough to save them.

The other women — in particular, Emily — pin their own hopes on men and are painfully (and repeatedly) let down. No man, in fact, is trustworthy in this novel, and none is redeemed. Fair enough. Still, every character, up to and including the men, is portrayed as complicated, feeling, and capable of real attachment, even if patriarchy inevitably trumps all.

Reading Dale’s book, I recalled being a DC high-schooler in 2016: the sense of urgency — of political emergency — that raised our young voices in protest and moved droves of us to the streets, to the U.S. Capitol, and to our representatives’ voicemail. It was empowering to join a chorus of like-minded peers, to see our words in local papers, and, yes, to feel justified in cutting third-period physics.

My review copy of The Good Daughters was blurbed by Fiona Davis: “[This novel] feels fiercely relevant today.” I will go further and call it timeless.

Madeleine de Visé is a bookseller in Baltimore, MD.