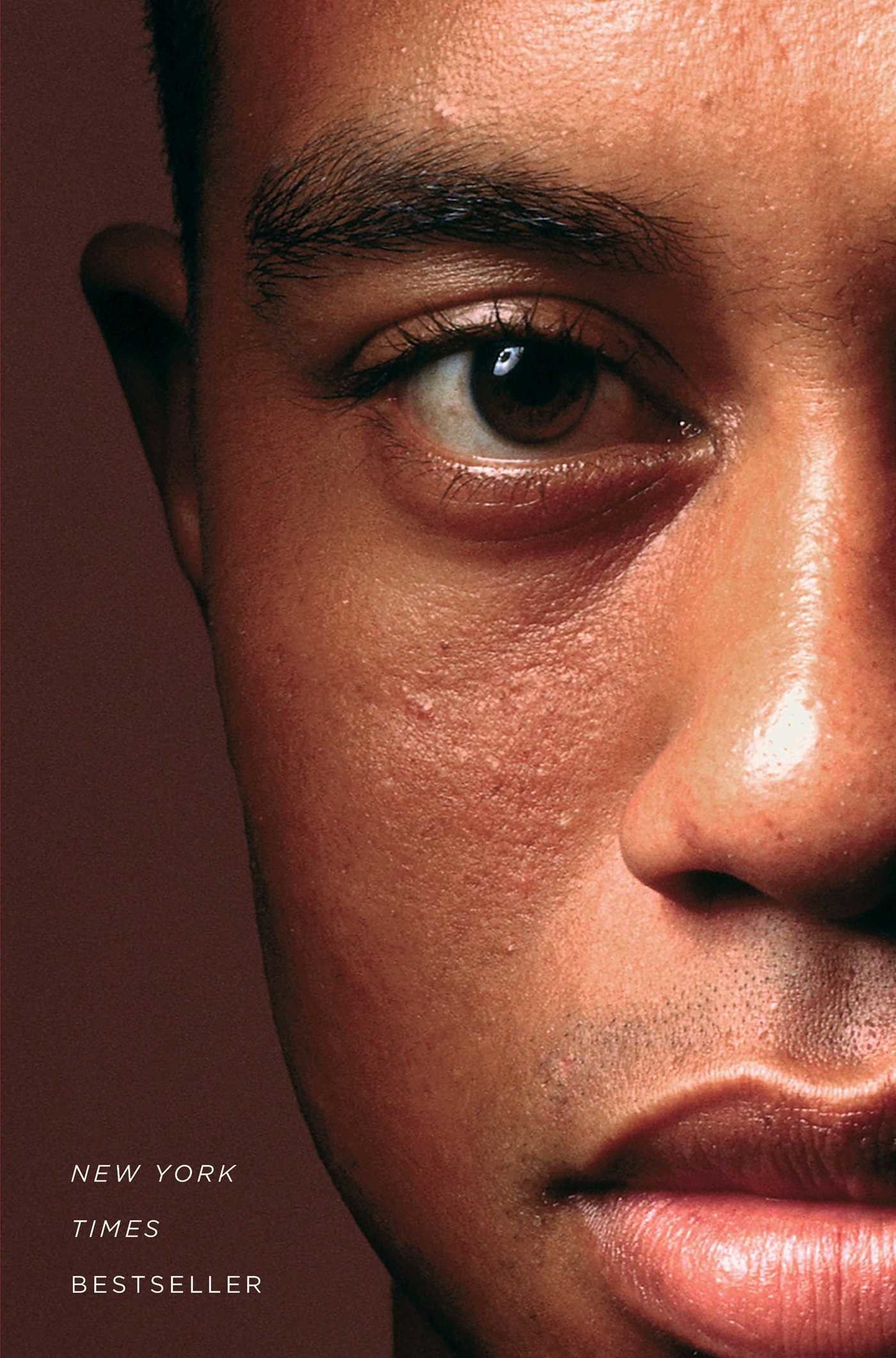

The Icon & the Idealist: Margaret Sanger, Mary Ware Dennett, and the Rivalry that Brought Birth Control to America

- By Stephanie Gorton

- Ecco

- 464 pp.

- Reviewed by Mariko Hewer

- December 5, 2024

The road to accessible contraception was long and bumpy.

With the uncertain state of reproductive healthcare in the United States today, it’s sometimes hard to remember how far we’ve already come. Stephanie Gorton’s The Icon & the Idealist: Margaret Sanger, Mary Ware Dennett, and the Rivalry that Brought Birth Control to America masterfully recounts that history, with all its highs and lows, through the eyes of two women instrumental in forwarding the cause.

At first glance, Dennett and Sanger seem likely allies in the fight to make access to birth control and sex education a reality. Both were born, Gorton notes, at the beginning of a “great silencing” aimed at suppressing information about “obscene” topics such as sex. Both were in favor of providing women with accurate information about birth control, and both cut their teeth mailing pamphlets and books to that effect, often running afoul of anti-vice activist Anthony Comstock and his Comstock Act. (First signed into law in 1873, these regulations threaten abortion rights even now.)

Yet as both women rose to prominence in the movement, the nuances of their positions drove them into opposition. When an optimistic Sanger asked Dennett’s fledgling National Birth Control League (later to morph into the Voluntary Parenthood League, or VPL) for support, Dennett proclaimed her too much of a lawbreaker and firebrand.

“This meeting was an inflection point for Sanger and Dennett’s alliance, such that it was, and it warped their previously cordial relationship,” writes Gorton. “When she insisted that operating within the law was the best and most effective path, Dennett implied Sanger had acted otherwise for her own glorification, or at least that personal ambition played into it.”

Understandably, Sanger took Dennett’s rejection personally and often reacted to her rival spitefully. The women did, however, differ significantly on policy issues. Whereas Sanger promoted a bill with “the avowed object of so modifying the present law that only physicians and nurses will be permitted to give birth control information,” Dennett favored a more egalitarian stance that attempted to connect with women directly.

Sanger’s American Birth Control League (ABCL) and the VPL frequently worked at cross-purposes, even while the women were campaigning on the same issue in the same place. They wrote letters to the senators supporting their rival’s legislation, urging those lawmakers to join forces with their own side instead. Still, neither woman was always successful or satisfied. After a failed lobbying season on behalf of the ABCL in 1926, Sanger wrote wryly:

“The more I have to do with Congressmen, the more I believe in birth control and sterilization.”

While Gorton does an excellent job illuminating Dennett’s and Sanger’s differences on policy and strategy, she also implies that the women’s personalities and very ways of thinking may have been so contradictory as to leave little room for agreement or compromise. On Dennett’s resolving to produce a “polemic [that] would discuss the legal status of birth control,” Gorton explains, “it is telling about the kind of reader and thinker Dennett was that she assumed readers would be more powerfully persuaded by a book of legal reasoning than by a tale of underdog heroism or a radical manifesto, the genres Sanger was most drawn to for her own books.”

Despite — or perhaps, in part, because of — Sanger’s and Dennett’s fierce lifelong rivalry, birth control and sexual education have remained at the forefront of the nation’s social consciousness since the early 1900s, with Dennett once expressing to a journalist her hope that “the time may come when sex physiology is taught in schools.” As current political forces seek to take us back, Stephanie Gorton’s excellent work reminds us of how far we’ve come.

Mariko Hewer is a freelance editor and writer, as well as a nursery-school teacher. She is passionate about good books, good food, and good company. Find her occasional insights of varying quality on X and Bluesky at @hapahaiku.

.png)