The Impossible Man: Roger Penrose and the Cost of Genius

- By Patchen Barss

- Basic Books

- 352 pp.

- Reviewed by Stephen Case

- December 12, 2024

The pioneering physicist gets his due in this exceptional biography.

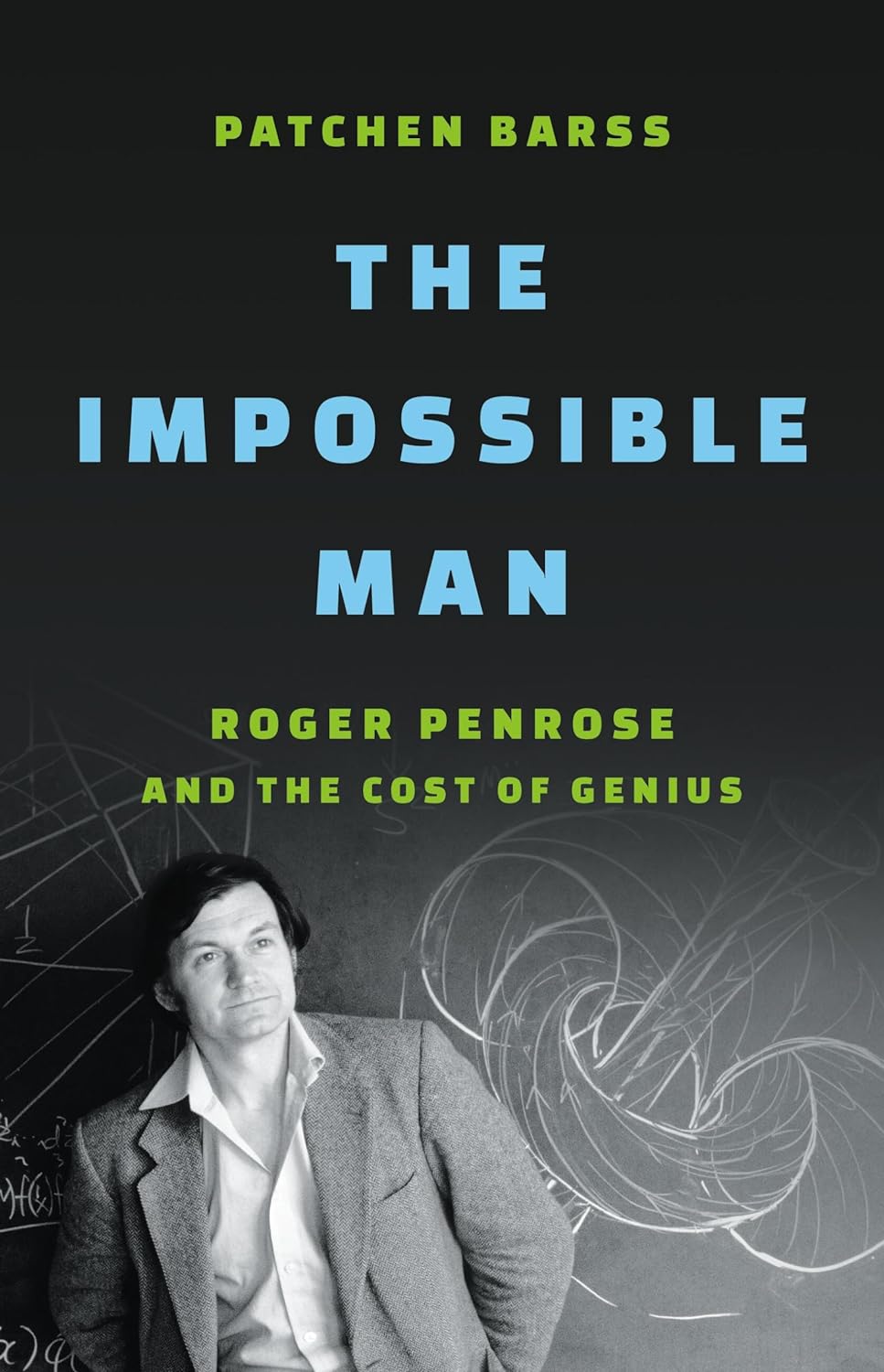

Future historians may well write that discoveries by theoretical physicists (e.g., atomic bombs, relativity, and black holes) overshadowed everything else in the 20th century. Few of those physicists have been more momentous than British Nobel laureate Roger Penrose. “Like magic,” his colleagues have said, Penrose’s breakthroughs “emerge [from]…miracles,” not from scientific drudgery, and his “insights seem to stem from some superhuman life form.”

For five years, Patchen Barss, a veteran Canadian science writer, spoke to Penrose “almost every week,” read beaucoup personal documents, and interviewed dozens of the man’s close acquaintances. The result is the lovely, sensitive, informative, and absorbing The Impossible Man, a new biography that ably recounts Penrose’s life and work.

Penrose’s father, Lionel, a domineering sort who forbade his mother, Margaret, from pursuing her own career as a physician, was averse to “shows of emotion [and] had a near-total lack of interest in the lives of his children,” Penrose recalls. As for Margaret, “There wasn’t [any] sort of warm hugging love about her,” either. (Penrose and his siblings called their parents by their first names, never Mom and Dad.)

Born in 1931, Penrose was, as a boy, spectacular at math, particularly exotic geometry. Emotional distance did not deter Lionel, recognizing his son’s gifts, from presenting demanding intellectual challenges to him. For example, he read young Penrose a science-fiction book about how an earthquake could transform a home “into a tesseract, the four-dimensional analogue of a cube.” (Huh? What in the dickens is a tesseract?) Knowing the world of normal perception has no fourth dimension, Penrose nonetheless felt “as though [the tesseract] had its own reality,” writes Barss.

In 1957, Penrose earned a Ph.D. in algebraic geometry from Cambridge. During his postdoctoral work, colleagues convinced him to switch to mathematical physics, which he fittingly “approached…through geometry.”

Five women, “each in her own way, made Roger’s career possible,” explains Barss. Two were his wives; three were not. With keen sensitivity, the author reveals more than readers might expect about the lives and personalities of these fine ladies and how they interacted with the sometimes-distant scientist.

In the mid-1960s, while crossing the street, Penrose “experienced a mental flicker…[which] changed…cosmology.” Reflecting on 30 years of science-community curiosity about quasars, he wondered whether “quasars fit every description of a far-distant singularity in the final stages of devouring a galaxy’s worth of matter and energy. No light would escape from the singularity itself, but the surrounding region would be incandescent. Could singularities be real after all?”

In what Barss calls “the biggest advance in relativity since Einstein,” Penrose cleverly coaxed out of Einstein’s own general-relativity equations proof that “every light ray, every spatial vector, even the arrow of time itself converged on a single point. They all came to a halt. Density and space-time curvature went to infinity. Relativity had broken down…He had solved the singularity problem. He had found a general solution to describe a gravitational collapse that had eluded him — and the world — for years.” This was, in other words, the theoretical foundation for black holes (a term not coined by Penrose). Not until the early 1970s was their actual existence confirmed by observation.

At the time, Penrose, then an Oxford don, was an outside evaluator of Stephen Hawking’s Cambridge dissertation. Drawing heavily on Penrose’s work, Hawking quickly invented the notion that a cosmological singularity was the starting point of the universe. Hence, “the Penrose singularity theorem swiftly morphed into the Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems,” writes Barss.

“It rankled Roger that they now shared credit. He felt his original work was a revolution and Stephen’s work was a refinement.” However, “Stephen’s medical situation [ALS] was public knowledge. Roger…avoided public pettiness and strove not to begrudge Stephen his rapid ascent.” Barss adds that this combination of collaboration and muted rivalry continued for more than 40 years, until Hawking’s death in 2018. For his own pathfinding work, Penrose won a share of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Today, independence of mind divides Penrose from others in his field (he has even “asked physicists to [drop] the very idea that the universe began with the Big Bang”). A reviewer went so far as to characterize Penrose’s 2016 book, Fashion, Faith and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe, as “an explosive study from an eminent refusenik.”

Penrose admits that many of his recent concepts remain unproven; open-minded consideration is all he asks from fellow researchers. Now 93 and nearing the end of his bedazzling career of boundless, brilliant brainstorming, some may wonder of Penrose: Has he lately lost it? Or does he stand proudly — as always — far, far ahead of the curve? Stay tuned.

Stephen Case is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and serves as its treasurer.