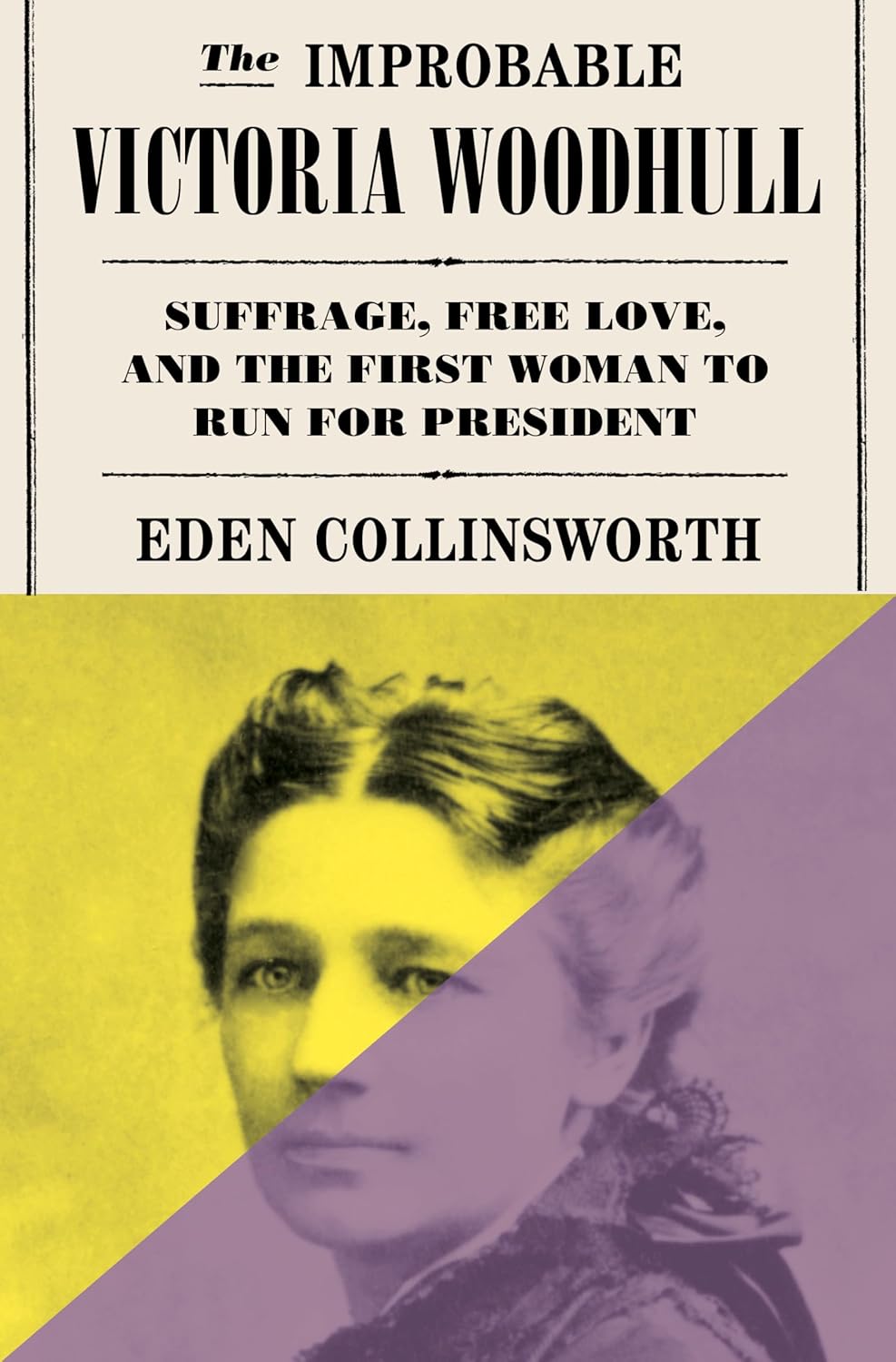

The Improbable Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and the First Woman to Run for President

- By Eden Collinsworth

- Doubleday

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Paula Tarnapol Whitacre

- September 30, 2025

A looseness with the facts undermines this work’s credibility.

In one of those sudden, severe storms we had over the summer, my copy of The Improbable Victoria Woodhull got soaked. Worried about completing this review, I spent days with towels, a hair dryer, and spreading the pages open in the sun to turn the sodden lump back into a readable if bloated book.

If Victoria Woodhull had been in a similar predicament, she would’ve found a way not only to get another copy but to wrangle a refund for the damaged one (never mind that a reviewer’s copy comes free of charge).

Woodhull pushed the limits in everything she did, from her hardscrabble upbringing in Ohio to her death in 1927 at age 88 as a wealthy widow on an inherited estate in England. Her father, Buck Claflin, was a “con man, swindler, and cheat” (her words), and her mother communed with spirits. Among their 10 children, Victoria and her sister Tennessee, known as Tennie, were the most successful in fusing their parents’ qualities with astounding amounts of chutzpah to move between poverty and wealth, scandal and fame several times over.

Mr. Claflin trained his daughters to perform as “amazing child clairvoyants.” In the 1840s and early 1850s, the family traveled from one small, gullible town to another, and the two girls financially supported the rest of the clan. At age 14, in part to escape, Victoria married a semi-quack, full-on addict named Dr. Canning Woodhull. A few years later, she said she was “called” to leave him and return to work as a medium alongside Tennie. As author Eden Collinsworth points out, “The cunning they used to survive a hustler’s childhood had become a streak of ruthlessness in their adulthood.”

Through their spiritual skills, good looks, and Victoria’s “vision” to move to New York City, the sisters met, or connived to meet, Cornelius Vanderbilt. He was 74; they were in their 20s. They convinced the uber-wealthy scion that they could connect him with his dead mother and deceased favorite son; he, in turn, took them “on a rollicking joyride through unregulated capitalism.” With Vanderbilt’s backing, the two former clairvoyants opened the first women-owned stock brokerage in America.

But Victoria wanted more. She published a weekly newspaper, gave lectures on free love and other topics, and, as this book’s title suggests, “improbably” decided to run for president. With the help of the powerful Rep. Benjamin Butler, she became, in 1871, the first woman to speak before a House of Representatives committee to promote women’s suffrage. The Susan B. Anthony/Elizabeth Cady Stanton crowd initially welcomed her participation but distanced itself when Victoria’s personal ambition overtook her commitment to the cause. Collinsworth doesn’t explain Woodhull’s political views or actions but notes that she felt “destined to be famous, which would mean that her place among the women reformers would not be in the ranks, but at the top.”

Financial, political, and personal controversies caught up with the sisters in the late 1870s, and they moved to England to start anew. They both married wealthy men and set about to scrub their less-than-savory American pasts.

And thus, The Improbable Victoria Woodhull actually begins in the Reading Room at the British Museum in 1893. The institution and its director, a man named Mr. Garnett, must respond to a libel suit brought by Woodhull, then 55, and bankrolled by her husband, John Martin, because the collection housed years-old, unflattering publications about her exploits in the U.S. Throughout the book, Collinsworth drops mentions of staid Mr. Garnett (we don’t learn that his first name is Richard until chapter 50) as a foil to cast Woodhull’s complex life in stark relief. The author writes:

“I am convinced that, to the very last, Mr. Garnett thought of Mrs. Woodhull as a puzzle that had withheld the satisfying clicking sound of its pieces falling neatly into place.”

That double conjecture — Collinsworth projecting onto Garnett, who is, in turn, projecting onto Woodhull — is an example of what I found most frustrating about this work. Collinsworth writes in an author’s note at the front of the book, “I have, when up against the limitations of the historical record, endeavored to accurately understand and re-create the motivations of the historical figures herein.” To a certain extent, that’s what biographers have to do. However, the author’s statement, combined with minimal endnotes and other sourcing, make the line between fiction and nonfiction unclear.

Woodhull surely would’ve approved of blurring the line between fact and fiction (there I am, with my own conjecture), but in this regard, I’m more like stodgy Mr. Garnett. In a purported biographical work, even about someone as outrageous as Victoria Woodhull, authorial re-creations should not be presented as fact.

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre is the author of A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, a biography of abolitionist and suffragist Julia Wilbur (who attended Woodhull’s 1871 testimony in the House of Representatives). Her book Alexandria on Edge: Civil War, Reconstruction, and Remembrance on the Banks of the Potomac is under contract with Georgetown University Press.