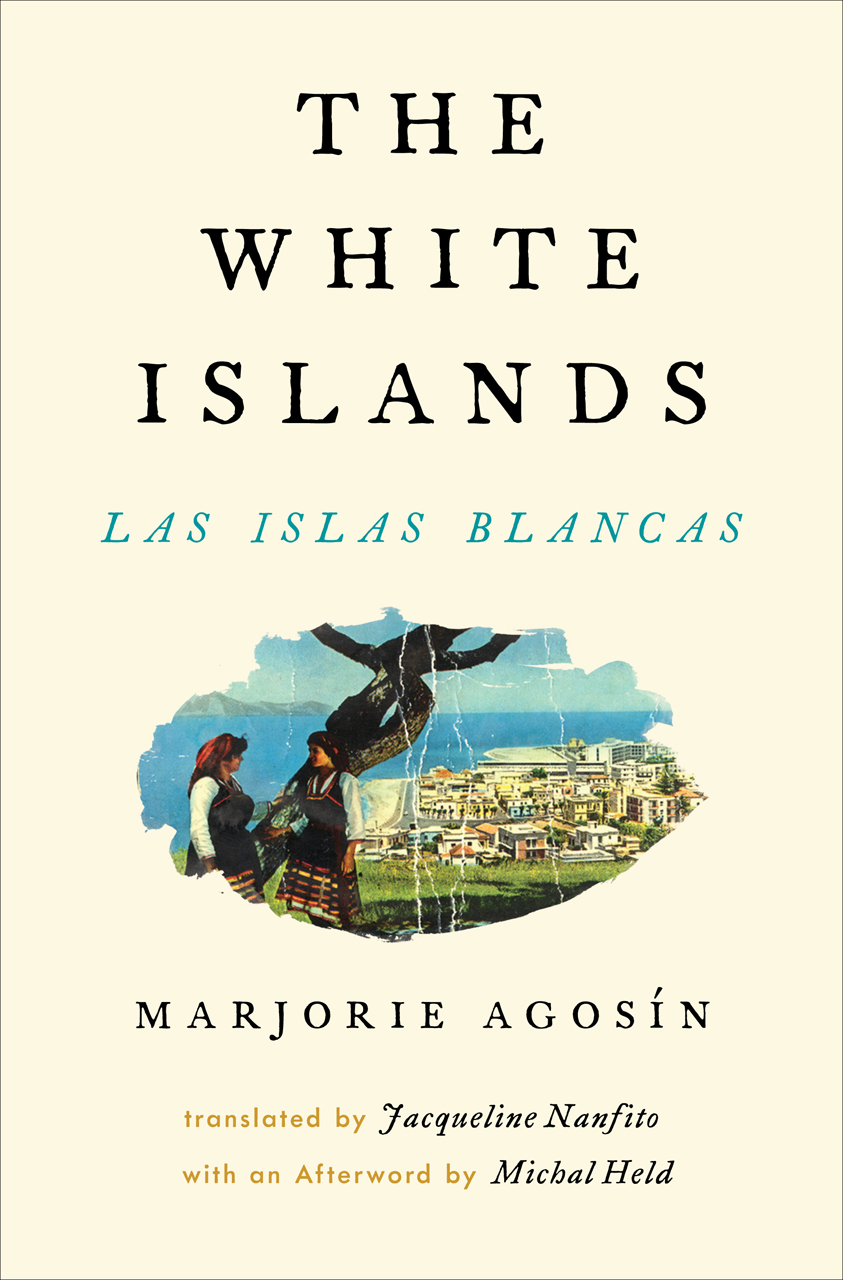

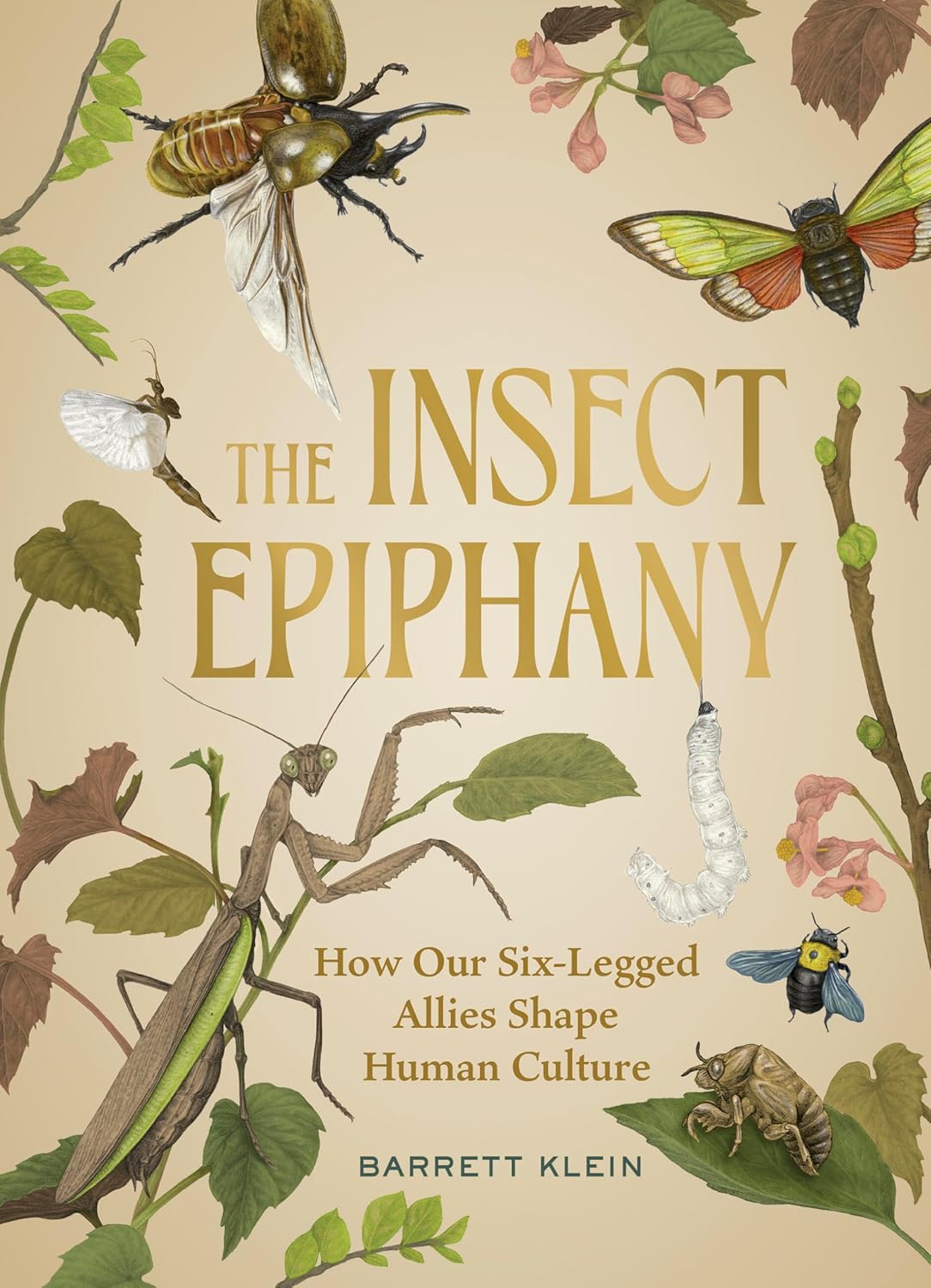

The Insect Epiphany: How Our Six-Legged Allies Shape Human Culture

- By Barrett Klein

- Timber Press

- 368 pp.

- Reviewed by Elizabeth McGowan

- November 1, 2024

Isn’t it time we stopped reflexively squashing bugs?

Who among us hasn’t spontaneously slapped a stinging bee, swatted a blood-sucking mosquito, or squished an ant marching intrepidly across the kitchen counter — without giving the loss of those tiny lives a second thought?

One likely candidate is entomologist Barrett Klein.

The author of The Insect Epiphany admits that ridding the world of the minuscule fraction of certain species of flies, fleas, caterpillars, cockroaches, and termites might eliminate some human annoyances and diseases, keep homes intact, and squelch damage to agricultural crops. But, he wisely emphasizes, the benefits of all that buzzing, creeping, and biting far outweigh the drawbacks attributed to six-legged pests.

Klein cites none other than conservationist and Harvard professor E.O. Wilson, the late, great “ant man,” who referred to insects as “the little things that run the world” because of their incalculable value as pollinators, seed-dispersers, tillers of soil, food for others, and nutrient-, waste-, and mineral-recyclers. Silencing the quintillions — it’s estimated there are 1.25 billion insects for each human — comes with consequences.

As the book’s title indicates, the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse biology professor and founder of the Pupating Lab devotes the bulk of this new work to explaining the infinite ways insects have inspired human innovation in art, architecture, food, clothing, medicine, music, and technology.

Unfortunately, Section I, “Working with Them: Symbiosis,” opens with a tediously long chapter on silk. Its 33 pages delve into silkworm moth minutiae, with briefer mentions of butterflies, caddisflies, and other species of moth that also spin silk. He compounds the too-much-detail problem by including roughly 10 pages on spider spinners, while clearly stating that these eight-legged brethren are arachnids, not insects.

By Section II, “Making Them: Genesis,” I felt as if I were slogging through a textbook crammed with lengthy series of information dumps to cover all the bases instead of well-crafted stories highlighting the most intriguing insect-human connections. At that point, my own epiphany was that a reader shouldn’t have to wade through 220 pages of a 368-page tome to reach what should be the heart, soul, and theme of this volume — how insects influence our art and architecture.

Klein’s buzzworthy passion emerges on page 221, when he details his pre-academic career as an insect fabricator, first at a natural history display-making studio in Missouri’s Ozark Mountains and then, impressively, at the American Museum of Natural History’s exhibition department in New York City.

That chapter segues into a thoughtful but too-short conversation with architect, fashion designer, and champion boxer Eugene Tssui. The Californian’s reverence for insects is evident in how he incorporates attributes of dragonflies, honeypot ants, and termites into buildings he designs. More of these observations, please. It seems an ideal place to further explain how artists use insect likenesses and actual insect bodies or products such as silk, shellac, or beeswax in their pieces. That captivating topic lost the spotlight it deserved by being incongruously folded into an earlier, cluttered section that lends itself to skimming.

The last section of the book, “Becoming Them: Metamorphosis,” is a sometimes bizarre look at how humans fight, dance, act, dress, and sound like insects. As offbeat as all of it is, the prose emphasizes Klein’s dedication to nurturing an appreciation for creepy-crawlies that humans overlook at their own peril.

Despite my gripes about the textbook approach, I’d be remiss in not mentioning the lovely illustrations throughout and the illuminating anecdotes (some before page 221) worth reading word-for-word. For instance, by laying their eggs in oak trees, gall wasps aided in the formation of a stable ink source the Western world relied on from medieval times to the late-19th century. To fend off damage caused by wasp larvae, the trees form a gall, an abnormal, tumor-like swelling that the invading parasite counts on for shelter and food. Tannic acid from galls, enhanced with other additives, was the basis for the ink used in sketches by Leonardo da Vinci, drawings by Rembrandt, and seminal U.S. documents like the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Relatedly, it was compelling to find out that René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur turned to wasps in 1719 when tasked with solving the paper shortage plaguing Europe. In lieu of recycled linen, the French entomologist — who earlier had investigated the viability of spiders as a source of silk — suggested humans pay attention to the layered paper nests that wasps construct from gnawed wood. By 1765, Jacob Christian Schäffer acted on that advice by experimenting with wasps’ nests, as well as pine cones and green algae, to fabricate paper.

In the subsection “Using Insect Bodies,” Klein regales readers with an enlightening personal anecdote about a night hike with an insect twist in a Costa Rican rainforest. Threading his way along a narrow trail, he stumbled across legions of leaf-cutter ants marching up and down a tree. Carried away by an opportunity for spontaneous science, he became alarmed when the light shining from his headlamp was dimming fast.

Fortuitously, he’d deployed that same headlamp earlier that evening to lure a bioluminescent click beetle into a vial. When his battery died, he held the vial close to the ground and let the beetle’s glow guide him the half-mile or so back to the research station. Later, he learned that long-ago islanders in the West Indies found their way in the dark by tying this same type of beetle to their toes.

Another eye-opener explains the Central Intelligence Agency’s valiant but ultimately doomed attempt to transport a wee listening device. The “bug,” nicknamed the Insectothopter, mimicked first a bumblebee, then a sleeker dragonfly. However, unlike the CIA, Tssui spies on insects for guidance on sustainable blueprints that contrast with our wasteful, toxic, and outdated structures.

“The study of insects gives me insights into the mind of nature,” the architect told Klein. “They fully understand their immediate surroundings and create accordingly. They are our teachers.”

Longtime energy and environment reporter Elizabeth H. McGowan, based in Washington, DC, writes for the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism. She has won numerous awards, including a Pulitzer Prize for “The Dilbit Disaster: Inside the Biggest Oil Spill You Never Heard Of” as a staff correspondent for InsideClimate News. Bancroft Press in Baltimore published her memoir, Outpedaling “The Big C”: My Healing Cycle Across America, in 2020. Follow her on X and Facebook.