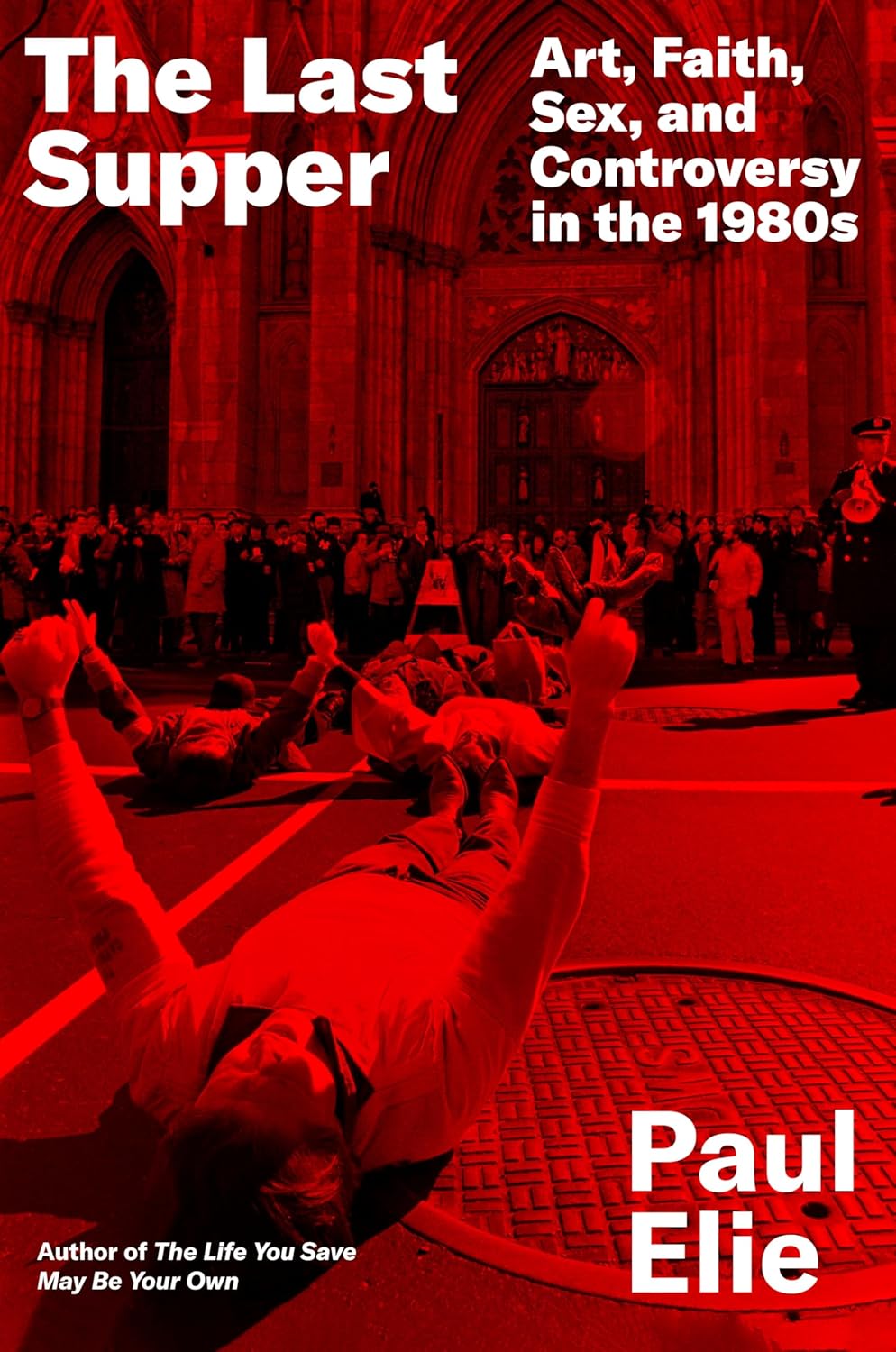

The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s

- By Paul Elie

- Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- 496 pp.

- Reviewed by Pierre Le Pelletier

- June 11, 2025

Do the culture wars of 40 years ago explain where we are today?

A good book review is a snapshot of the period during which it was written — typically, the two to four months between the piece’s assignment and its publication. A reasonable peg on which the humble reviewer can usually hang his narrative hat, then, is the humdrum drama of daily life over a quarter of a year or so.

The period I spent pondering Paul Elie’s The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s — a book about crypto-religiosity — overlapped with the first 100 days of the second Trump regime. (No! Don’t make this review about him!) The U.S. is now led by an apparent Christian nationalist whose in-your-face crusade is characteristically un-cryptic.

Those same weeks saw the death of Pope Francis following his final, always political Easter service; the announcement of a forthcoming Martin Scorsese documentary about Francis; and the selection of the first-ever American pope, though not the one, thankfully, our artificially intelligent overlords proposed. Finally, the period included a strategic rejection of right-wing populism in two G20 nations, perhaps signaling a global shift of sorts. These happenings are all worth mentioning, but they left this reviewer’s hat blowing in the wind.

The Last Supper, at nearly 500 pages, feels like a lengthy literary mixtape recorded off AM radio to accompany another recent title: Jesus Wept: Seven Popes and the Battle for the Soul of the Catholic Church by Philip Shenon. If Shenon’s book leans Conclave, Elie’s swings Scorsese.

A senior fellow at Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs and a regular contributor to the New Yorker and Vanity Fair, Elie is the author of two previous books, The Life You Save May Be Your Own and Reinventing Bach, both of which were National Book Critics Circle Award finalists. I trust this big-picture story in his hands.

Elie’s 1980s are a long decade in a short century; the period 1914 to 1991 has been here and elsewhere named the age of extremes. His approach is maximalist; managing to reference dozens upon dozens of creatives, public figures, key works, and pathways of cause-and-effect with the best kind of intertextuality, it’s not always clear how many connections elude even the author. There’s a lot going on here, but Elie harnesses each example supporting his thesis. Reading this book requires breaks, but the narrative is coherent.

Elie’s definition of crypto-religious art is straightforward — “work that incorporates religious words and images and motifs but expresses something other than conventional belief.” Such work doesn’t necessarily reveal what its creator believes. (Sort of like God and Creation, yeah?) For Elie, crypto-religious artwork proliferated in the 1980s:

“In that moment, figures in what we call popular culture engaged questions of faith and art and the ways they fit together with an intensity seldom seen before or since.”

He pins his maximalist narrative on portraits of key figures and their works and deeds over time; most need just one name as they are sui generis: Warhol, Dylan, Bono, Prince, Sinead, Madonna, Rushdie, and others. There may have been XIV Leos (to now), but the events Elie describes are singularly summarizing signifiers for many middle-aged readers: HIV/AIDS, fatwa, Tiananmen. But in our time of oversimplicity, he reminds us that tearing up a photo of the pope on TV — as Sinead famously did on “Saturday Night Live” — can have multiple complicated, enigmatic meanings.

His critical analysis of the crypto-religious reminds us how cynical the culture wars can be. His extended portraits of creatives like Leonard Cohen, Patti Smith, and Robert Mapplethorpe provide a poetic counterpoint to the moral panic stirred up by dubious figures like Cardinal John O’Connor and Senator Jesse Helms — as do the numerous Catholics who, for example, faced the AIDS crisis with humanity. In particular, Elie’s use of the religious concept of the scapegoat is effective.

In 1980, 42 percent of Catholics in the U.S. attended Mass once a week; in 2025, the age of Mass media, the number was 24 percent. Now, one can take communion alone, at home. The end of the age of extremes brought about the end of the crypto-religious; the Marilyn of the late 1990s was not at all like Warhol’s of the mid-1960s. Some surely argue we’re in the age of the antichrist, but there have always been people like that around.

As I expected, Elie makes the point that the 1980s culture wars help explain wherever it is that we are today, and he’s right. The end of all things crypto-religious left a vacuum yet unfilled. In his epilogue, he reaches toward the violent religious extremes of 9/11, but I kept thinking of Columbine as the end of one extreme era and the beginning of another. Jesusland and “Jesus Camp” are no longer ironic. The pope and the antichrist are both American. The fatwa was issued from inside the house, even if the scapegoats are the same as they ever were.

Pierre Le Pelletier has a Ph.D. in comparative literature (earned under his given name). This is his first publication in the Independent. He welcomes queries at [email protected].

.png)