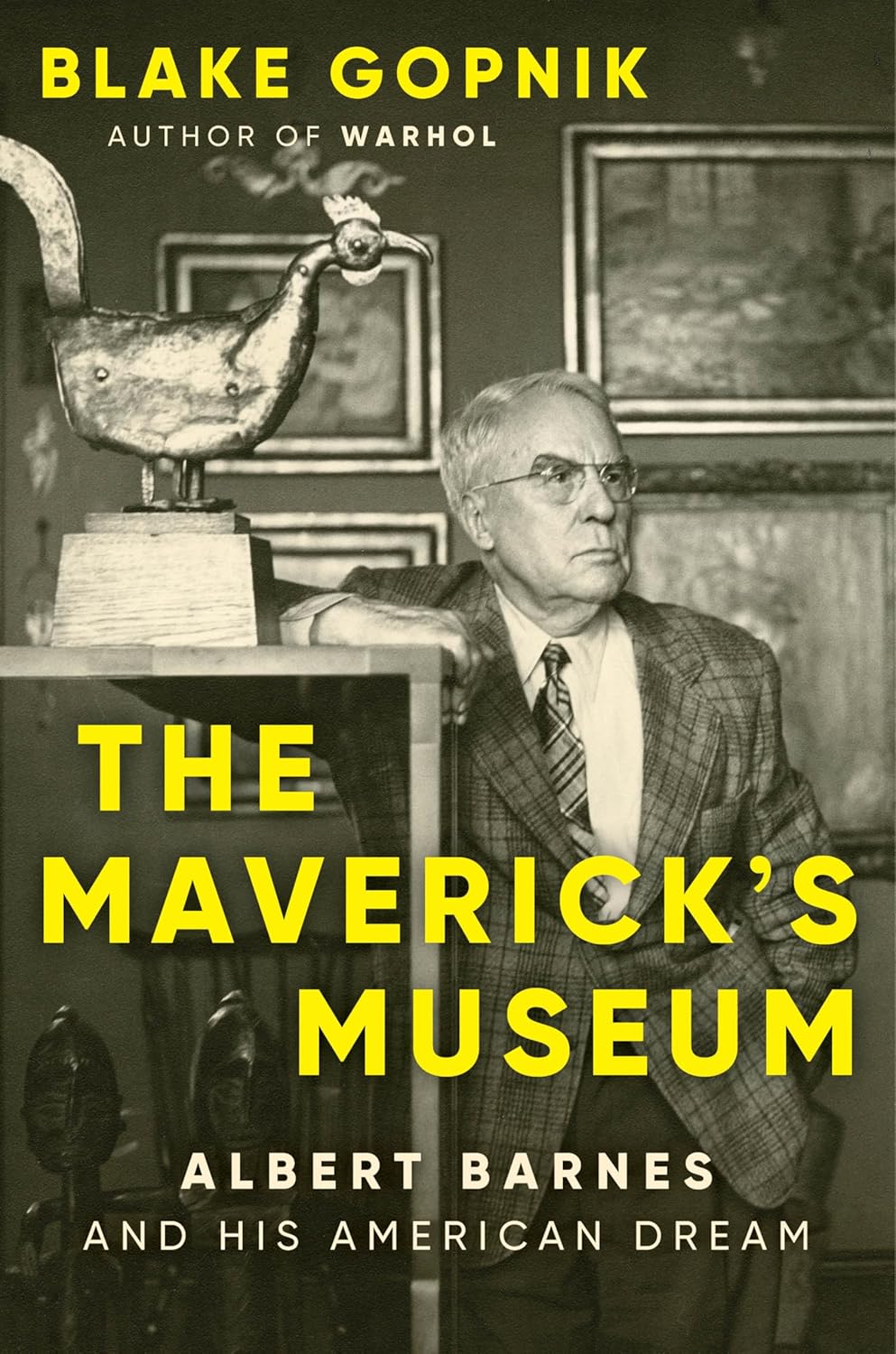

The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and His American Dream

- By Blake Gopnik

- Ecco

- 416 pp.

- Reviewed by Jethro K. Lieberman

- April 15, 2025

How an irascible iconoclast built a temple to modern art.

“The Barnes.”

The culturally literate — readers of the Independent, for example — command a range of stock phrases they can bandy about as needed: “white whale,” “theory of relativity,” “for whom the bell tolls.” And more likely than not (depending on age, reading habits, line of work, and degree of inebriation), they can also retrieve an associated tag: Moby-Dick or maybe even “obsessive pursuit,” etc. But much of the time, that’s probably the extent of it.

So, too, with “The Barnes.” Until I read Blake Gopnik’s charming and fascinating The Maverick’s Museum, the best I could do with the name (which I’ve uttered perhaps twice in my entire life) was recall that it’s some sort of art museum in Philadelphia.

The result of Gopnik’s prodigious research is a lavishly illustrated book rich with storylines. It is simultaneously the biography of a true American eccentric and self-made multimillionaire; the story of art collecting in the first half of the 20th century; a glimpse into the French and African art scenes; the origin story of an abnormal museum; a tale of Philadelphia; the chronicle of unusual friendships; and an account of many other topics, including the philosophy of aesthetics and democratic education.

Albert Coombs Barnes was born into an impecunious family in Philadelphia in 1872 and, for much of his childhood, lived in or near the Neck, a grim slum of squatters’ housing and waste heaps from nearby industry. His father was an alcoholic Civil War veteran who’d lost an arm and was rarely able to provide for the family of four. The younger Barnes took on meager jobs from an early age. His experiences and acquaintances from those days gave him lifelong empathy for the working class and for Black people as individuals and as a race.

Possessed of a strong will and intellect, Barnes passed the rigorous admission exam to tuition-free Central High School, which conferred a bachelor’s degree upon graduation. From there, he earned an M.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. He practiced medicine briefly, then worked for a chemical company, where, in the days before antibiotics, he and a colleague invented Argyrol, an antiseptic that cured gonorrheal blindness in newborns. A company they launched to manufacture and market the drug quickly made their fortunes, allowing Barnes, 30, to pursue his longtime interest in art.

The developing aesthete possessed a complicated, contradictory personality. He was odd for his time in his support of Black workers, professionals, and artists, and of Black culture generally. Throughout his life, he engaged, in Gopnik’s words, in a “quite unaverage agitation for equal rights.” Befriending his mostly Black employees, he provided salaries well above market rates, paid for their healthcare, and supported them in various ways, while also mingling with Black intellectuals and elites. At the same time, Black “stereotypes clearly lurked in Barnes’s psyche.” Writes Gopnik:

“Barnes’s commitment to Black culture and Black rights was clearly real, and heartfelt…It’s also clear that Barnes, like many a philanthropist, liked championing the underdog in part because it made clear, to others but especially to himself, that he was an overdog.”

His paradoxical nature was on display not merely in his dealings with and commentaries on Blacks; he also engaged in antisemitic tropes and acts of philosemitism, showing the same generosity to particular people who happened to be Jewish that he showed to those who happened to be Black. And when fury overcame him — which it frequently did — he was an equal-opportunity vituperator, hurling abuse at many, including upper-class whites and close colleagues, whom, he would be surprised to learn, did not immediately respond with enthusiasm when he extended an olive branch, as if nothing had happened, a day or two later.

Barnes was aware of his abrasive approach, speaking “with some comic pride of his ‘ingrained habit of manipulating vituperation, venom, vindictiveness and personal abuse.’” But, as Gopnik notes, “The sheer clamor of his attacks hides the fact that they were almost entirely verbal, and only rarely caused any actual damage.”

When his growing art collection was moved from his home, the new Barnes Museum building in Philadelphia was described as “the first public museum in this country devoted to modern art,” predating the Museum of Modern Art by four years. It held hundreds of important paintings by Renoir, Cezanne, van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Seurat, de Chirico, and other well-known modernist painters that, since 1912, Barnes had been assiduously acquiring (the story of which is told at some length). The official inaugural day for the Barnes Foundation, which owned the building and collections and which would underwrite the many educational programs of the museum, was celebrated on March 19, 1925, exactly 100 years to the day that I write this paragraph.

The centerpiece of Barnes’ understanding of art was that the subject matter was irrelevant; what counted were lines, shapes, colors, and textures. Gopnik explores this theme in depth, showcasing Barnes’ attempts to sell this philosophy and the conundrums it created.

Despite the contradictions, Barnes persevered in his principal objective to have his foundation’s staff teach (tuition free) his gospel of art, education, and democracy — the “Barnes method” — to those who would come. But then, you couldn’t view the collection without taking the courses. His aesthetic theories were also briefly taught in Barnes-sanctioned classes elsewhere, but they all quickly came a cropper. As Gopnik notes, “Few alliances with Barnes ever lasted.” Paradoxically, policies adopted to support the museum’s educational mission “meant the near-total exclusion of the typical museum-going public,” leading essentially to a closed-door policy, exceptions being made solely at Barnes’ whim.

And so it continued: Smart people were hired and then quickly fired for violating Barnes’ often unfathomable strictures; universities were courted and then rebuffed; and eminent thinkers (Bertrand Russell among them) were warmly embraced but soon spurned. It all came to an abrupt end in July 1951, when Barnes, who’d amassed multiple moving violations over the years, sped through a stop sign that he himself had pressured the authorities to install at a dangerous highway intersection. He was broadsided by a tractor-trailer carrying ten tons of paper. His car somersaulted, and he died on impact.

His wife of half a century, Laura (a praiseworthy woman about whom Gopnik says little), lived until 1966. After her passing, under provisions of Barnes’ will that (as usual) he’d been thinking of changing, control of the Barnes Museum passed to Lincoln University, a nearby Black institution that he’d wooed in order to carry on his mission.

Many contretemps and lawsuits later, the Barnes is, at long last, a public institution. Hundreds of thousands of people now visit annually (this year, I hope, including me). Read the book, and you’ll want to go, too.

Jethro K. Lieberman took his only history of art course 65 years ago — when Impressionism was no longer particularly modern — but the Barnes Museum, had he known of it, would likely have been closed to him.