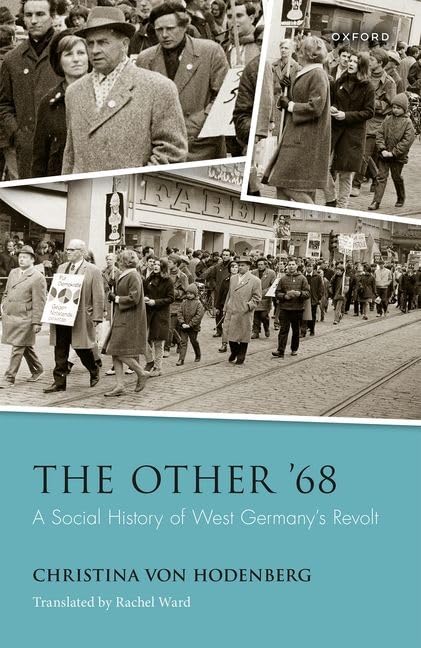

The Other ’68: A Social History of West Germany’s Revolt

- By Christina von Hodenberg; translated by Rachel Ward

- Oxford University Press

- 240 pp.

- Reviewed by Andrew M. Mayer

- November 28, 2024

How three generations viewed the cultural shift in Bonn and elsewhere.

Christina von Hodenberg has written in The Other ’68 a unique volume that chronicles the often-unsung role played by ordinary people, especially women, in the West German revolution of 1968. Mining 600-plus taped interviews — the oldest featuring middle- and working-class Germans born around 1900 who participated in the Bonn Longitudinal Study of Ageing, or Bolsa — she sets out to capture the turbulent late 1960s through the eyes of three generations who lived through it: the elderly, the middle-aged, and the young.

“My attempt to consider 1968 from a social history perspective and, in the process, to expand the grounds under investigation, fits with related trends in historical research into the sixties in Western Europe,” the author writes in her introduction. “Despite growing awareness of the ways this history has been distorted, it is still rare to find book-length studies on activists or groups who do not conform to the dominant storyline…The gendered aspect of 1968 is similarly under-researched, yet it is a fiercely contested field.”

In the book, published in Europe in 2018 but only now available in English, von Hodenberg reframes the long-held prevailing view of Germany’s late-1960s social revolution: Namely, that it comprised mostly male college students. These included men from the “Sixty-Eighter” generation, who came of age around 1968, and the “Forty-Fivers” — sometimes referred to as the “Hitler Youth Generation” — who were still kids when the Nazis ruled. Members of this latter cohort include Helmut Kohl, Rudolf Augstein, and Joachim Fest.

As Tony Judt noted in Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, the Forty-Fivers escaped the blame put on their parents, who were adults — complicit or otherwise — during the Third Reich era. Yet these same Forty-Fivers experienced déjà vu as their own sons and daughters (the Sixty-Eighters) grew to disrespect them for not adequately sharing in their elders’ collective guilt over the debacle of World War II.

This conflict of generations had been exacerbated in 1961, when historian Fritz Fischer declared Germany solely responsible for the outbreak of World War I. This was hotly disputed by Forty-Fivers, who felt the assassination of Austria’s Franz Ferdinand in 1914 was the true spark that led to the Great War, during which, many Germans believed, England, France, and Russia intentionally let the lights dim across Europe in a desire to defeat Kaiser Germany.

The 1968 social revolt actually began in May 1967 with a demonstration against a visit by the Shah of Iran to Bonn and West Berlin. Groups of largely Bonn university students, flanked by three Iranian students, protested the shah’s intolerance of free speech; German police attacked and arrested 58 protestors. This ignited a period of anti-establishment and antiwar protests throughout Germany and in France, Italy, the United States, and elsewhere.

The gold mine in von Hodenberg’s study are the so-called “Bolsa Recordings.” These audiotaped interviews revealed that, in many cases, the Forty-Fivers were in conflict with their children, the Sixty-Eighters, because their own parents — born at the end of the 19th century or beginning of the 20th — had been overly strict with them. Or, at least, with the girls. Female Forty-Fivers were not permitted to date until age 18. If they disobeyed and got in “trouble,” they had to marry. Many were subsequently denied the chance to get a university education.

When the Sixty-Eighters reached maturity, many of their fathers wanted them to follow the traditional route: marriage and children. The Forty-Fiver mothers, however, denied such opportunities themselves, wanted more for their daughters. Surprisingly, the tapes reveal that members of the Forty-Fivers’ parents’ generation also supported expanded freedoms for female Sixty-Eighters.

This caused estrangement in many middle-class families as girls, hearing the clarion call of 1960s liberties, embraced the Cohn-Bendit principles of revolution, demanded women’s empowerment, and applauded the advent of the Pill. (Beate Klarsfeld’s slap of interim chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger in November 1968 embodied the Sixty-Eighters’ disgust at former Nazis holding positions of power in West Germany.)

In The Other ’68, von Hodenberg succeeds in showing that women had a much more significant role in the 1960s social revolution than previously acknowledged, and that their efforts led to expanded opportunities for women. Change may not have come quickly vis-à-vis women’s position in German society, but it did come.

Andrew M. Mayer is professor emeritus of humanities and history at the College of Staten Island/CUNY.