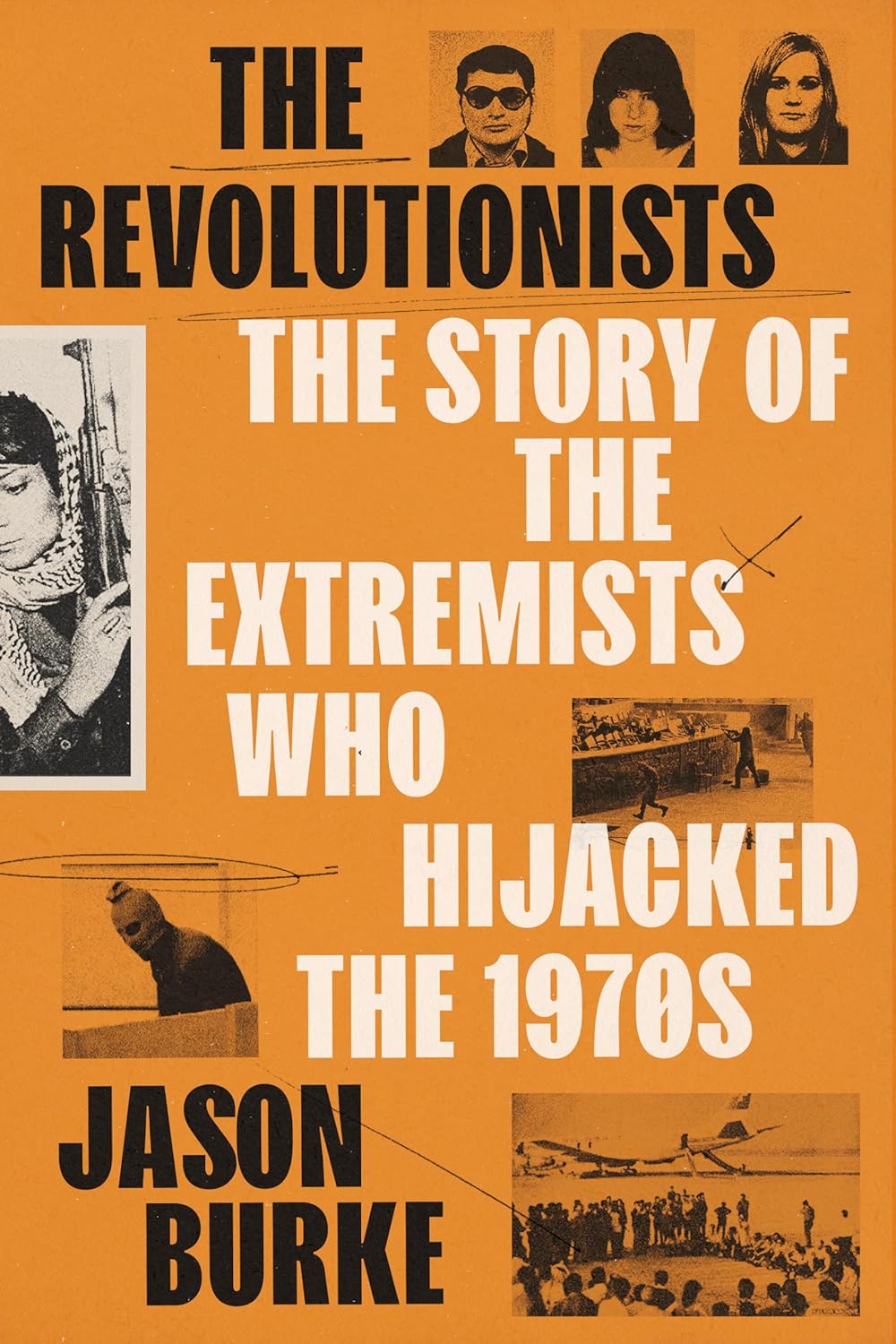

The Revolutionists: The Story of the Extremists Who Hijacked the 1970s

- By Jason Burke

- Knopf

- 768 pp.

- Reviewed by C.B. Santore

- February 13, 2026

Meet some of the true believers behind the sunglasses and masks.

“They’re all gone,” Jim McKay, the ABC sportscaster, told a stunned world watching the 1972 summer Olympics in Munich. Millions of viewers had watched the day before as armed men from a militant Palestinian faction stormed the Israeli athletes’ compound, killed two team members, and took nine others hostage. The next day, McKay announced the remaining hostages had been killed.

Author Jason Burke, the international-security correspondent for the Guardian and an expert on radical Islam, has 30 years of experience reporting on terrorist events like this across Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia. This background informs The Revolutionists, his mammoth work tracking extremists during the 1970s.

The sheer breadth of Burke’s research is staggering: Source notes take up just shy of 60 pages. He counts among his sources hijackers, soldiers, activists, national-security officials, spies, diplomats, and victims. His bibliography includes books, press articles, scholarly pieces, documentaries, podcasts, and official archives, including those of the CIA and the Carter and Reagan presidential libraries.

In the book, Burke unmasks the balaclava-clad individuals who perpetuated a spate of violence from 1967 to 1983. We learn about their backgrounds, see how they perceived the world, follow the paths they traveled, and hear about the people they met and how they learned from them. We find out where they trained and become acquainted with their likes and dislikes, even how they dressed.

The prologue, which reads like the opening of a spy novel, follows Palestinian militant Leila Khaled and Sandinista Patrick Argüello in the leadup to their first joint mission. Writes Burke:

“They made a handsome couple, witnesses later said. She, petite and pretty, in her faux Hispanic outfit, complete with bolero waistcoat and sombrero; he, much taller, wearing a grey suit, with his hair brushed back in a thick, dark wave.”

Burke presents his subjects as individuals, not archetypes. For example, he tells us that Venezuelan political terrorist “[Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, aka Carlos the Jackal] enjoyed a crepe stuffed with mincemeat in a paprika and cream sauce” when dining with comrades. A fashionable dresser himself, Ramírez encouraged his wife, Magdalena Kopp, to wear the smart, expensive clothes he preferred to see her in.

Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, leaders of the Red Army Faction (eponymously referred to as the Baader-Meinhof Group), targeted West Germany but made connections with the Palestinian nationalist group Fatah for training. They traveled to a Fatah camp in Jordan, near where Khaled had trained, to learn how to build explosive devices. They, like other revolutionaries, took advantage of such camps in Jordan, Syria, and Libya that offered cover for jihadist training.

Yasser Arafat makes appearances throughout The Revolutionists, alternately encouraging and funding terrorism and trying to remain at arm’s length from the violence. Other well-known actors like Muammar Gaddafi, Ayatollah Khomeini, and Osama bin Laden are present, too, but the most interesting parts of the book are the depictions of lesser-known figures like Ali Hassan Salameh, a protege of Arafat. Burke describes Salameh as “physically fit, his broad chest revealed by unbuttoned shirts, and casually elegant.” Surprisingly, Salameh, possibly part of the Munich Olympics plot, was also a CIA asset.

The recounting of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s assassination is compelling for the details Burke provides about the attackers. One, Khalid Al-Islambouli, a platoon commander in the Egyptian military, was able to thwart the usual security measures taken before the president’s public appearances:

“On the eve of the parade, orders were given to render harmless all the weapons belonging to Islambouli’s unit by removing their firing pins…Islambouli, who knew this would happen, replaced the missing firing pins.”

The book begins in the 1960s, when a surge in hijackings and kidnappings by leftists was facilitated by increased international air travel and magnified by mass media. Initially, the purpose of such attacks was to gain attention — if possible, without casualties — for a particular cause. By the early 1980s, when revolutionary fervor in the West quieted, the threat from radical Islamic groups grew. These revolutionists’ goals, explains Burke, were no longer limited to gaining international attention via high-profile events but expanded to purposely targeting civilians with brutal violence.

This insight is not unique. Bruce Hoffman’s definitive Inside Terrorism follows a similar historical arc of what he calls the “internationalization of terrorism.” Hoffman analyzes a longer period, beginning with the Reign of Terror that followed the French Revolution and continuing through to the 1990s. His approach is more thematic than Burke’s, discussing, for instance, varying definitions of terrorism, the motivations for suicide missions, and the modern terrorist mindset.

Still, The Revolutionists makes for a worthy companion, especially for students of terrorism. Although its sheer heft may put off general readers, they’ll find it surprisingly approachable. Chapter titles like “Sand, Sea and Kalashnikovs” and “Death on the Nile” are catchy, while the chapters’ endings give tantalizing hints of what’s coming next. To wit: In the chapter preceding the one on the shah of Iran’s fall, Burke concludes by writing, “The answer [to the attempted overthrow] would come just under a week later, when the shah’s tanks moved back into Tehran for a final battle with the revolutionaries.”

We all know how that turned out.

C.B. Santore is a freelance writer and editor in East Hampton, CT.