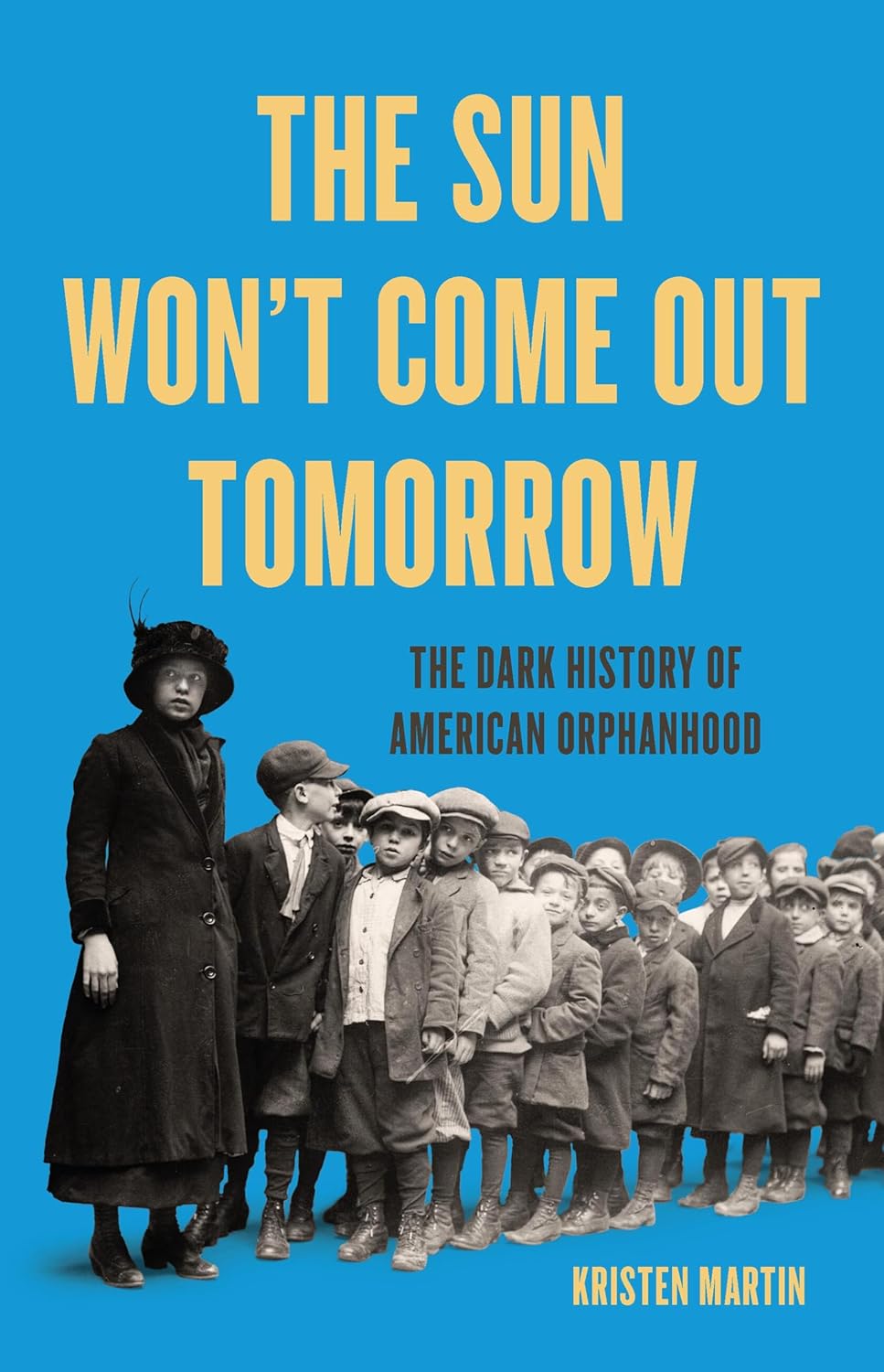

The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow: The Dark History of American Orphanhood

- By Kristen Martin

- Bold Type Books

- 352 pp.

- Reviewed by Alice Stephens

- January 21, 2025

Revealing the ugly truth behind the pretty stories.

From the Depression-era comic strip “Little Orphan Annie” to the 2013 bestseller Orphan Train, orphans abound in American popular culture, shaping the public’s idea of orphanhood. The epitome of the American orphan is Annie, introduced to the public via the comics, then firmly enshrined in hearts by the eponymous musical and subsequent movie and TV adaptations. By tweaking the name of the hit song from Broadway’s “Annie” for the title of her fascinating study, The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow: The Dark History of American Orphanhood, author Kristen Martin reflects the ugly truth behind the popular narratives.

Martin has a personal stake in the subject: She was left an orphan at 14 years old. “My parents’ death irreparably cleaved my life in two,” she writes. “[B]efore was the seemingly impregnable safety and love of a nuclear family in the Long Island suburbs; after was a grief that felt impossible to speak in a culture that still refuses to look head-on at death and mourning.”

In fact, as Martin makes clear, Americans refuse to look head-on at many things, preferring saccharine tales of brave orphans who pull themselves up by their bootstraps to the sensible, practicable policies that would protect vulnerable children. Asserts the author:

“The gap between the stories we tell ourselves about orphans and the lived experiences of those children reveals the narrative that America wants to construct about itself: we are a nation that values the nuclear family, rallies around children in need, and believes all young people have promising futures. In reality, the history of how our country has dealt with dependent children is full of classism, racism, and hypocrisy fueled by capitalism and moral panics, where only some are deserving of strong familial ties.”

Through analyses of cultural works ranging from the many iterations of “Annie” to TV shows like “Party of Five” and the book series The Boxcar Children, Martin contrasts sentimental, upbeat narratives with grim historical reality. “Each time we regurgitate Annie’s story, we allow ourselves to believe the orphan’s struggle is one with individual causes and individual answers. In doing so, we overlook the systems — economic, religious, political — that have made orphans out of real children like Annie and that continue to control their fates.”

For example, rather than being the secular institutions depicted in “Annie,” orphanages typically operated under the aegis of religious organizations, with the goal of converting souls. And contrary to popular narratives, many young inmates were not actually orphans; they had at least one living parent who entrusted their care to an orphanage due to poverty. In the absence of governmental oversight, religious institutions were free to choose which youngsters were worthy of assistance, effectively declaring orphanages only for white children.

Reflecting the punitive attitude toward the poor, Charles Loring Brace, an ordained Congregationalist minister and founder of the Children’s Aid Society, came up with a solution to the swelling numbers of New York City urchins living in poverty: ship them by train to rural communities to live with farming families and learn the value of hard work. From 1854 to 1929, orphan trains sent destitute children to the heartland, where they were taken into unvetted homes to be used as child labor in exchange for room and board.

Meanwhile, the same holy organizations that were ministering to “orphans” strongly influenced attitudes toward unwed mothers, “punishing and policing sexuality and controlling reproduction,” writes Martin. While men were not held accountable for their role in reproduction, women were shamed into abandoning their children so that a more deserving woman — one who was married — could bring them up instead. The real mother was literally erased from official documents, resulting in a permanent separation of families. Additionally, another type of family separation was happening in the name of assimilation; generations of Native American children were forcibly removed from their homes to be sent to boarding schools or adopted into white families.

In 1912, the U.S. government finally created a department overseeing child welfare. “The federal government’s first bureaucratic and financial foray into taking responsibility for the welfare of all American children — not just the Native children whose lives it had long been upending — thus came 136 years after our country’s founding.” But the same grim policies persisted.

Instead of fixing systemic problems with policies that would help single mothers keep their children, government assistance today comes with impossible demands for struggling families, such as work requirements and mandatory classes. Under the charge of “neglect,” the system separates poor families, especially Black and Native American ones, placing children into a dysfunctional foster-care system that hampers rather than enhances their chances for future success.

Foster care has become an industry, consuming billions of federal dollars. Continuing the long tradition of vindictive policies toward the poor, the Adoption and Safe Families Act, passed in 1997, “requires that states initiate [termination of parental rights] proceedings against parents whose children have been in foster care for fifteen out of the past twenty-two months. This clock starts as soon as children are forcibly removed from their families.” The children then become eligible for adoption.

As an adoptee who was mislabeled an orphan in order to be adopted, I appreciate Martin’s effort to replace specious tropes with indisputable evidence of America’s duplicitous notions of family. The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow is a deeply researched, comprehensive rebuke to sentimental depictions of orphans as plucky adventurers, exposing the shameful reality of this country’s treatment of its most vulnerable citizens throughout its history and up to this very moment.

Alice Stephens is the author of the novel Famous Adopted People. Despite official paperwork declaring her a South Korean orphan, she had living parents at the time of her adoption.