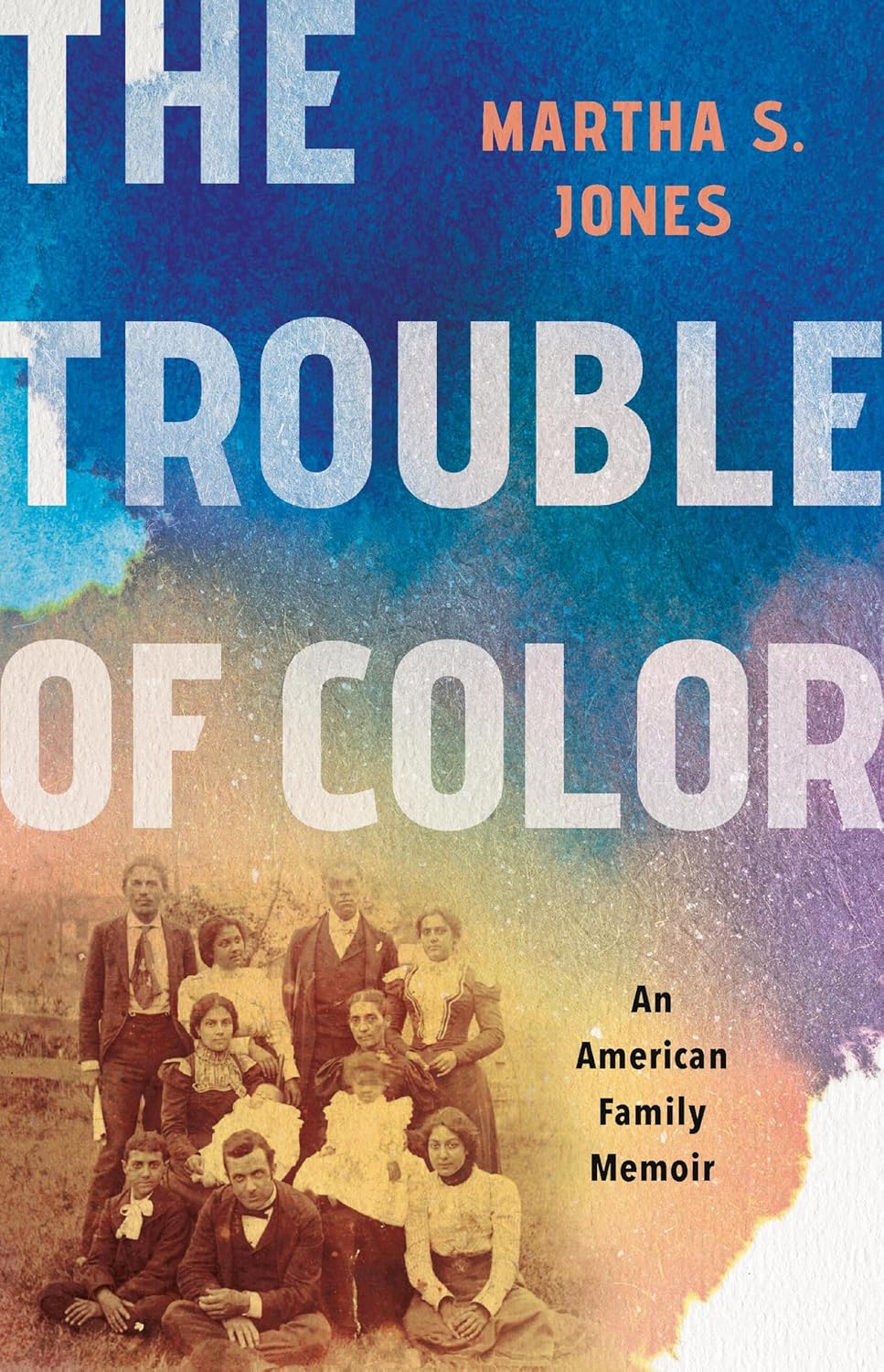

The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir

- By Martha S. Jones

- Basic Books

- 336 pp.

- Reviewed by Diana Pabst Parsell

- May 29, 2025

A deeply personal quest to understand mixed-race identity.

Identity is a complicated business. Our sense of self and our place in the world affect us as profoundly as genes that imprint biological traits, yet identity isn’t fixed and certain, like green eyes or brown hair.

It’s a lesson Martha S. Jones learned a few weeks into college. Raised on Long Island the daughter of a Black father and a white mother, she grew up identifying as Black. Then, while giving an oral report in a Black-studies class, she found her assumptions rudely challenged. Midway through her presentation, a male classmate — an activist in the school’s Black Student Union — interrupted her in a fiery outburst: “Who do you think you are?”

As Jones recalls in The Trouble of Color, the put-down seemed to question not just her intellectual ability but her very right to be there, with her “skin too light, hair too limp,” and diction and manners too suburban.

The confrontation sparked lingering confusion and anguish about her identity. “My self-discovery,” she writes, “began in that cinder-block and linoleum upstate New York classroom.” Now, nearly five decades later, The Trouble of Color is her exploration of what it means to be “colored”: someone of mixed-race ancestry who doesn’t slot neatly into the standard worlds of Black and white.

A prize-winning historian and legal scholar at Johns Hopkins, Jones has written four previous books that take a big-picture view of little-examined areas of Black history, especially in regard to women’s achievements. Her acclaimed 2020 work, Vanguard, widened the lens on America’s suffrage movement by showing the considerable political power that Black women wielded in the long fight for voting rights.

The Trouble of Color is similarly wide-ranging in its examination of “coloredness.” Here, however, Jones made the leap from her usual scholarly style into memoir. She did so, she says, to allow her emotional response to the highly personal subject. Plus, the memoir form seemed well suited to her focus on the strong influence of family in forging identity. Interweaving the historian’s craft with personal reflection, she probes her own family’s past, seeking to understand how her ancestors navigated “the jagged color line” through five generations, dating back to slavery. The result is part genealogical quest, part meditative journey told in a smooth style that unfolds as a discussion between author and reader.

(An appealing element of the book is its large and rich cast of characters. But because their stories span multiple chapters and generations, a genealogical chart would’ve been helpful.)

Jones draws on her ancestors’ experiences to inform discussion of broader themes — like the issue of “passing” as white. She relates family stories of how her high-spirited great-grandmother Fannie “danced along the color line” at will, whenever it suited her interests. Jones is taught by her father that passing is something she must never do. Nor was it the path chosen by her light-skinned grandfather David Dallas Jones, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate who served for three decades as president of the historically Black Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina. Given his pride and remarkable achievement, it stuns the author to find his legacy diminished in published references to him as a “white businessman.”

Armed with a family photo, Jones follows another paper trail to rural Kentucky in search of her great-great-great-grandmother Nancy, who was born in 1808 and assumed the surname of the Bell family that enslaved her. One archival request brings an unsettling moment. “Be careful, now, who you talk with about this,” a librarian quietly cautions. The racially delicate questions Jones is asking, the woman explains, have a bearing on some of the town’s most prominent families. It’s a reminder of how fraught the issue of slavery remains even to this day.

When new findings do turn up, they bring painful truths into sharper relief. Like her own mother before her, Nancy was subject to the sexual violence that occurred routinely on plantations in the South. Records show she raised at least 14 children, some from her white master, others from unions with Black men, including a legal marriage after she was freed. What does the word “family” really mean, the author ponders, when households crossed the color line? Under such conditions, lines of kinship blur.

As a trained historian, Jones puts her faith in facts. But historical records don’t always provide answers or resolve contradictions. What is she to make, for example, of a much-repeated family story claiming blood ties to the wealthy John Jacob Astor? Sometimes, she writes, families tell the stories they need to tell — “in a process of tellings and retellings.” The truth can’t always be fully known. In sections of the book where documentary evidence is scarce or nonexistent, she uses the latitude afforded by memoir to imagine the tenor of past lives.

Among the truths Jones arrives at is the realization that community defines kinship as much as color and blood do. Families, she writes, are knitted together through marriage, rituals, and everyday life, both in their own time and across generations.

The book’s one weakness, for me, is related to its structure. As is typical in memoirs, the narrative sets us up at the start to expect the story of an individual struggling to solve a problem. Jones alludes often to “troubles” related to the color of her skin. Yet the nature of those difficulties isn’t clear because she withholds most details of her own circumstances until the final chapters. I found her coming-of-age story one of the most emotionally powerful parts of the book. It left me wishing we’d met that smart, sensitive, and resilient young woman earlier on.

Nonetheless, The Trouble of Color is an important book that deepens our understanding of the Black experience in the United States. At the same time, it transcends race as an American saga about family, identity, and belonging.

Diana Pabst Parsell is a writer, editor, and former journalist who has worked for a variety of publications and several major science organizations. Her debut book, Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees, was a finalist for the Society of Midland Authors’ 2024 prize for biography and memoir. She lives in Falls Church, Virginia, and volunteers as a docent at the Library of Congress.