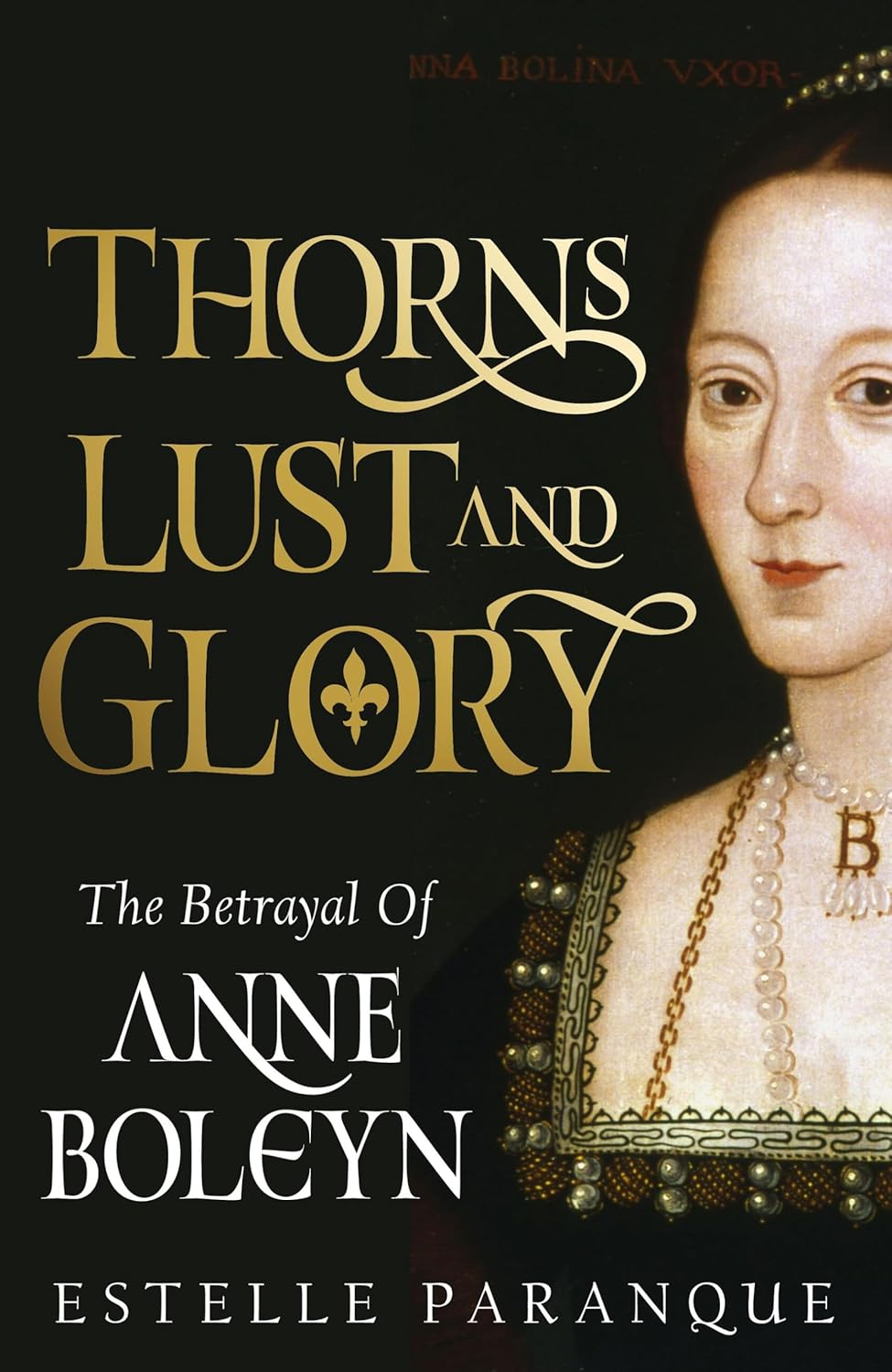

Thorns, Lust, and Glory: The Betrayal of Anne Boleyn

- By Estelle Paranque

- Hachette Books

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Bob Duffy

- November 25, 2024

An overly narrow focus hobbles this otherwise solid work.

Over the last 15 years, we’ve seen a surge of enthusiasm among non-academic audiences for Tudor-era bios and histories, not to mention works of historical imagination like Hilary Mantel’s Man Booker Prize-winning Wolf Hall (2009), which arguably ignited the trend. No surprise: The period — straddled at one end by the gargantuan Henry VIII and at the other by his cagey daughter, Elizabeth I — abounds in dazzling personalities. In Thorns, Lust, and Glory, Estelle Paranque zeroes in on one of the most controversial and fascinating of these somebodies, Anne Boleyn, Henry’s storied mistress and ill-fated second wife.

Paranque has given us an energetically researched — if somewhat narrowly conceived — take on Anne’s two-decade climb into the spotlight. The story begins with her sojourns as teenage lady-in-waiting to two queens of France and then, in the same role, with the English queen whom we know as the Spanish-born Catherine of Aragon. It’s here at Henry’s court, c. 1526, that Anne catches the king’s eye, and his pursuit of her kicks into gear. According to Paranque, the cosmopolitan Anne, her gaze fixed on a crown, holds the king chastely (or mostly so) at bay for seven years. And then, fully satisfied with his promise that the old queen will be set aside and Anne crowned, she yields:

“It has been rumored that the couple consummated their carnal relationship [in November 1532]…although no contemporary evidence exists to support this theory. It is certainly likely that Anne would have waited this long to consummate their relationship, because becoming queen was her goal, and she could not have afforded to give him an illegitimate child.”

That’s what Paranque claims, a bit too clairvoyantly perhaps, given the absence of “contemporary evidence.” Still, she’s not alone among scholars. Anne’s skill at deflecting the advances of the notoriously concupiscent Henry, it would seem, owed much of its success to the cultural vise grip of the Courtly Love craze (and Anne’s canny manipulation of its reluctant mistress convention) that pervaded Henry’s court. The king, otherwise used to the instant satisfaction of his every wishful urge, supposedly falls swooningly in line, inspired, or stupefied, by the spurned-but-ever-hopeful suitor role that Courtly Love assigned him. (Not all historians buy this view of the protracted non-consummation of the affair, but that’s a matter beyond the scope of this review.)

Nonetheless, Anne might indeed have played the long game brilliantly. She’d seen Henry’s mistresses come and go, her own married sister, Mary, among them. Plus, the resolution of “the King’s great matter” (i.e., a divorce from Queen Catherine) was anything but a sure bet, despite the assurances of Henry and his advisors.

The diplomatic tug-of-war over the divorce would drag on for years, embroiling European big-power relations: France on one side, Spain on the other. Pope Clement, meanwhile, the supposed decision-maker on the annulment, was playing for time, knocked off balance by the blooming Reformation to the north. What’s more, he was leery of alienating Henry, even as he (the pope) was under extreme pressure from — and briefly imprisoned by — the Spanish king (Queen Catherine’s nephew).

Long story short, by June of 1533, the more private tussle between Anne and Henry had certainly been settled. Six months pregnant, she marries Henry and, amid much pageantry, is crowned queen. Within a month, the pope abruptly annuls their marriage and excommunicates them both. In September, Anne gives birth to the daughter who will, 23 years later, become Elizabeth I. The child’s gender is a disappointment to Henry, who is banking on a son for dynastic reasons. Even so, this results in a period of marital calm, with Henry focused on consummating his lukewarm reformation by stripping his kingdom’s Catholic monasteries of their riches.

By 1536, Anne is pregnant again, but she suffers a miscarriage. This is too much for the king; Anne goes off to execution, tarred with trumped-up charges of adultery. She’s the first of two Henrician queens to suffer capital punishment for alleged adultery.

Sadly, Paranque’s perspective throughout is an almost exclusively diplomatic one. She’s thoroughly versed in the letters and related communications of a small handful of contemporary foreign observers, markedly the French and Spanish envoys to Henry’s court. These envoys report faithfully (though with opposing prejudices) on Anne’s rise and fall. Paranque provides context on the shifting-sands backdrop of the major powers’ rivalries for European dominance and, not insignificantly — given the religious circumstances and realpolitik of the era — their competition for papal favor.

And so, we’re left with a pretty narrow stab at Anne’s life and impact. Paranque, for all her fervency to court a gender-specific audience (note her book’s title), holds back potentially dramatic and narrative-enriching details. Notable among these is her failure to provide more than cursory detail about the plot to convict Anne of adultery with no fewer than five denizens at court, including her own brother and a royal musician.

There’s much lacking in Thorns, Lust, and Glory, but it’s an adequate introduction to Anne Boleyn’s life. Still, after reading it, you’re cheating yourself if you don’t follow up with any of the more substantial biographies.

Bob Duffy, a long-ago academic and Tudor specialist, is an occasional reviewer for the Independent.