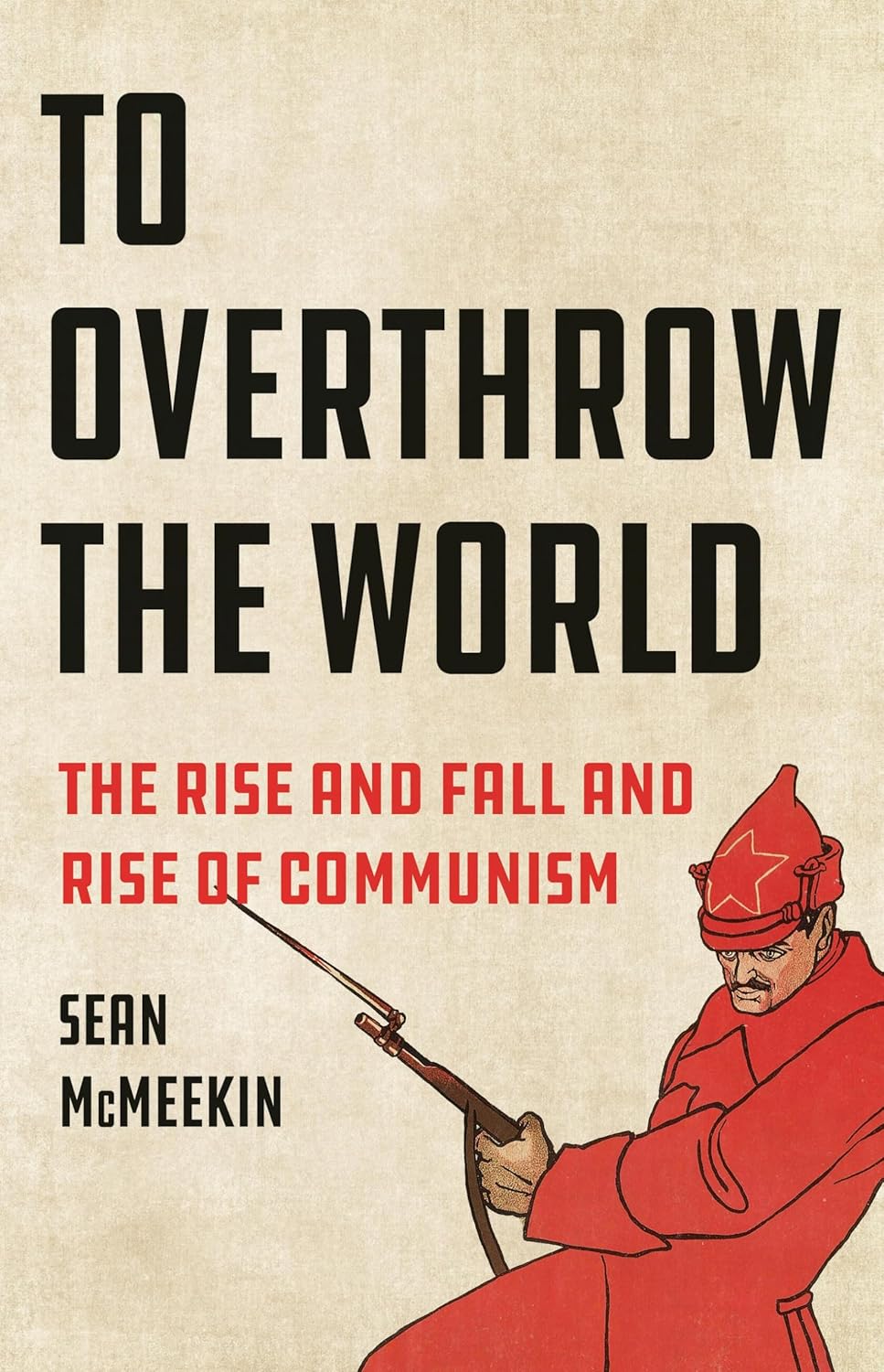

To Overthrow the World: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Communism

- By Sean McMeekin

- Basic Books

- 544 pp.

- Reviewed by Todd Kushner

- September 30, 2024

A right-leaning assessment of a leftist ideology.

Bard College history professor Sean McMeekin wrote To Overthrow the World at the height of the covid-19 lockdown after observing that some of his students defended Vladimir Lenin and other communist figures in class. He noted that none of them associated communism with totalitarian regimes and was concerned that they’d naively equated communism with social justice.

His resulting work convincingly disabuses idealistic views of communism but is tinged with an ideologically conservative hue. Among other things, McMeekin asserts that pandemic restrictions and the possible “persecution [of] people whose views dissent from the approved consensus of Western social and governing elites on a wide range of topics such as ‘climate change,’ immigration, race, sexual identification, or gender identification” are evidence that communism may be growing in appeal.

He points out that communists have never come to power via free elections; in fact, during the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, 75 percent of Russians voted against them. And in countries where they ruled, they took and maintained power through breathtaking displays of brutality. To wit, when assuming power, the Bolsheviks executed 15,000 people in the first two months of their rule; Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia killed 30,000-50,000 alleged collaborators in 1945; communist forces executed 20,000 “counterrevolutionaries” in the first year after Mao Zedong declared the People’s Republic of China; and the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia killed 1-2 million people (19-33 percent of the total population) in the 1970s.

Once communists solidified power, their brutality typically intensified; 3-4 million people, for instance, starved to death during Stalin’s agricultural collectivization campaign in Ukraine. The Red Army, upon “liberating” Eastern Europe from the Nazis, conducted systematic campaigns of rape and looting. Chinese communists launched a terror campaign in 1951 that enforced death and deportation quotas (one person killed and nine deported to labor camps per every 1,000) that resulted in up to 800,000 deaths. Further, 20 million Chinese died of hunger in Mao’s “Great Leap Forward.” The Communist regimes that perpetrated these atrocities were single-party dictatorships that attempted to control economies, societies, and the very lives of the people in whose name they claimed to rule.

According to McMeekin, communist parties have been able to gain and hold power because they were aided by outside forces. Lenin’s Bolsheviks were dependent on Germany for financial and military support. Western investors were responsible for much of the Soviet Union’s industrialization, and the Red Army in World War II was reliant on American equipment. Tito’s victory in Yugoslavia was due to airlifted American and British supplies. And Mao’s victory in China was dependent on Soviet largesse, although many of the arms Moscow supplied were regifted American lend-lease or captured Japanese weapons and munitions.

The author details communism’s characteristic centralized coercion. Lenin established the Communist International (Comintern) as a forum for communist parties worldwide. The Soviets ruthlessly used the Comintern to ensure these parties worked to serve the interests of the USSR and to purge them of any elements that were reformist, centrist, or patriotic toward their own countries. The resulting stripped-down versions of these parties subsisted on Moscow’s funds and obeyed Moscow’s orders.

McMeekin cites the nature of Soviet support for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War as an example of Russian manipulation of the international communist movement. The Soviets sent the Republicans a substantial number of arms and a couple-thousand troops — which no doubt boosted the USSR’s international standing among leftists — but did so for a price: 464 tons of gold bullion, a large share of Spain’s gold reserves. Meanwhile, they also sent significant numbers of political advisors and spies to infiltrate the Spanish government and eliminate any communist or anarchist elements not loyal to Moscow.

McMeekin is a gifted writer who conveys his ideas via a readable and engaging narrative. He is also an accomplished historian, having authored five prior books on Russia. In writing To Overthrow the World, he drew on archival records only recently made available; thus, he is able to present a more detailed picture than have previous books on the subject. Still, there are a few sections that could’ve used more editorial attention.

The first section, for one, discusses the intellectual roots of communism, but by the time the narrative arrives at Lenin’s efforts to seize power in Russia, that discussion has been abandoned in favor of a political/military focus. There’s nothing wrong with such a shift, but it makes the early chapters feel like an afterthought.

And readers should note that McMeekin has a reputation as an “ideologically driven conservative historian” whose prior books have been criticized for a fervent anti-communist bias that creates oversimplified analysis and distorted conclusions. To Overthrow the World also shows signs of ideological overreach. For example, McMeekin goes out of his way to denigrate the late Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein. He also criticizes the U.S. for supporting China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, claiming China made no concessions in the negotiations (U.S. negotiators disagree with this assessment).

Discussing the Soviet Union’s relations with countries emerging from European colonial rule, McMeekin describes Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser as “having clearly chosen sides in the Cold War, and not with the Americans.” This characterization disregards other evidence in the historical record indicating that Nasser’s preference was to buy arms from the U.S., but the conditions imposed by the Eisenhower administration (including the requirement that Egypt join a Western alliance) were too onerous for a country that had recently thrown off de-facto colonial rule. Similarly. McMeekin praises Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek for his “strategic sense and humanity,” when Chiang is also remembered for repression and corruption.

The rise of communism and its eventual fall in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe is one of the driving forces that shaped the 20th century, and it continues to influence our world today. With this book, McMeekin performs a valuable service in reminding us how and why these developments came about. Given his ideological bent, however, readers wanting a broader, more nuanced view of communism’s history should also consult other sources.

Todd Kushner is a retired Foreign Service officer with the U.S. Department of State. The views expressed in this review are his own and do not represent the views of the U.S. government.