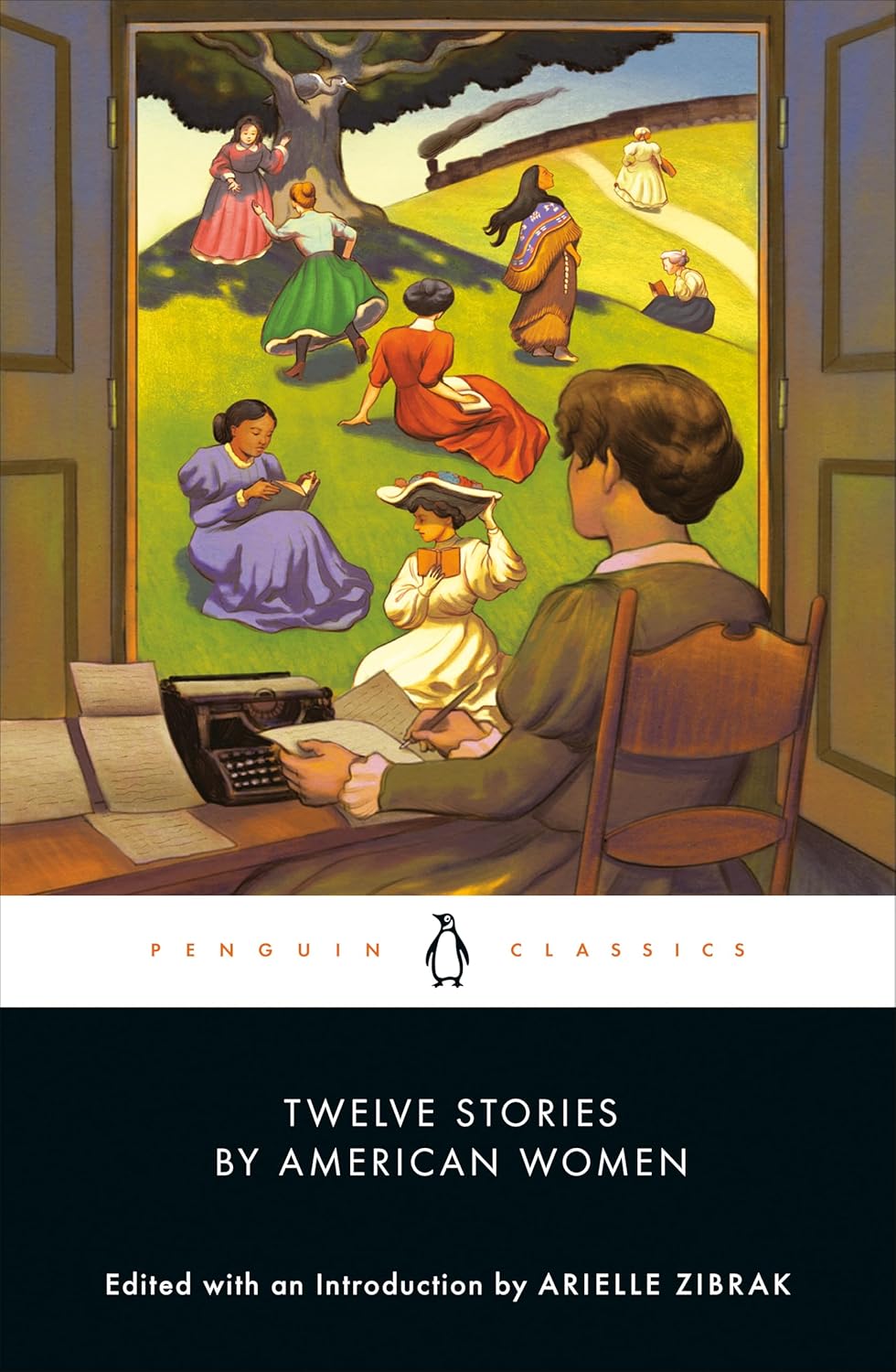

Twelve Stories by American Women

- Edited by Arielle Zibrak

- Penguin Classics

- 256 pp.

- Reviewed by David A. Taylor

- August 6, 2025

A worthy assemblage of mostly (and sadly) forgotten works.

People say we don’t know where we’re going until we see where we came from. And that’s why University of Wyoming professor Arielle Zibrak has done such a service in bringing out Twelve Stories by American Women, most of whom didn’t get read in their own time, let alone now. Her anthology traces a lineage of female writers who influenced future writers across generations. Along the way, they placed into the public record the concerns and interior lives of the half of the population rarely reflected there.

The best-known contributors here are Zora Neale Hurston, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Edith Wharton. Hurston’s 1926 story, “Sweat,” traces a case of karmic justice for a Florida woman and her husband. Gilman’s 1892 “The Yellow Wall-paper” was neglected for decades but gained renewed influence in the 1970s. And in Wharton’s “Souls Belated,” written in 1899, wealthy New Yorker Lydia, on the threshold of divorce, navigates the shoals of patriarchy while ostensibly enjoying freedom in Europe. When her lover assumes she’ll marry him once the divorce is final, she balks:

“It may be necessary that the world should be ruled by conventions — but if we believed in them, why did we break through them? And if we don’t believe in them, is it honest to take advantage of the protection they afford?”

Happily, the collection also showcases many unfamiliar names and highlights unexpected literary connections. Barbara E. Pope, whose 1896 “The New Woman” is included here, was an educator and writer from Washington, DC, whose fiction humanized Black life and showed Black women as smart, fully rounded characters. W.E.B. Du Bois championed her work and included “The New Woman” among a handful of pieces he curated for the 1900 Paris Exposition. In the story, the title character explains to her husband her desire to clerk in his law office, the way she once did for her father:

“‘The bargain was that you would practice law and I take charge of the home,’ she reminds him, ‘but neither of us must be selfish, and each will call on the other for assistance when needed.’”

Zibrak also features “Life in the Iron-Mills” by Rebecca Harding Davis. In the pre-internet era, the 1861 story wended its way through used-book shops and finally reached an influential voice in 20th-century feminist writing, Tillie Olsen. “I first read ‘Life in the Iron-Mills’ in one of three water-stained volumes of the Atlantic Monthly,” Olsen later recalled, “bought for ten cents each in an Omaha junkshop. I was fifteen.” She was struck by Davis’ words — “Literature can be made out of the lives of despised people” and “You too must write” — and tried to find more by the author:

“No reader I encountered had ever heard of the story…It was not until, in the reference room of the San Francisco Public Library, where I went lunch hours from work to read them, I learned who the author was…It did not surprise me that the author was a woman. At once I eagerly looked for other works by her. But there was no Rebecca Harding Davis in the card catalogue.”

Zibrak’s introduction is divided into the themes “Female Literary Professionalism,” “Marriage and Independence,” and “The Political Work of Women’s Fiction.” If the approach sometimes feels dutiful, it covers a lot of ground, restoring pieces from working-class women, communities of color, and Indigenous oral traditions.

Among other discoveries, I appreciated meeting for the first time Sui Sin Far, born Edith Maude Eaton in England in 1865. Her British father and Chinese mother brought their family to Canada in 1872, where, at 18, Edith started working as a type-setter for the Montreal Star to help support her parents and many siblings. She eventually moved up and down the West Coast and then onto Boston. Asserting her Chinese heritage in 1896, she began publishing stories as Far. “Mrs. Spring Fragrance,” the 1912 tale included here, poses the kind of relationship questions we still ask, including this one from a man speculating on his spouse’s solo travels:

“Was the making of American fudge sufficient reason for a wife to wish to remain a week longer in a city where her husband was not?”

Zibrak points out that when we read these authors together, it’s easy to assume they were ahead of their times. But she insists that each was “embedded in the prejudices and specific material conditions of their own historical moment,” and that they can’t answer questions for our time. “But they are our ancestors,” she concludes, “and by turning to them now, we assert the value of learning the past as part of our own story.”

David A. Taylor’s books include Soul of a People, about the WPA writers, and Cork Wars: Intrigue and Industry in World War II, which received an Independent Publishers Book Award for world history. He teaches writing at Johns Hopkins University and produces a history/culture podcast, “The People’s Recorder,” which was nominated for Best Indie in the 2025 Ambie Awards.