Twisting in Air: The Sensational Rise of a Hollywood Falling Horse

- By Carol Bradley

- Bison Books

- 232 pp.

- Reviewed by Diane Kiesel

- November 22, 2024

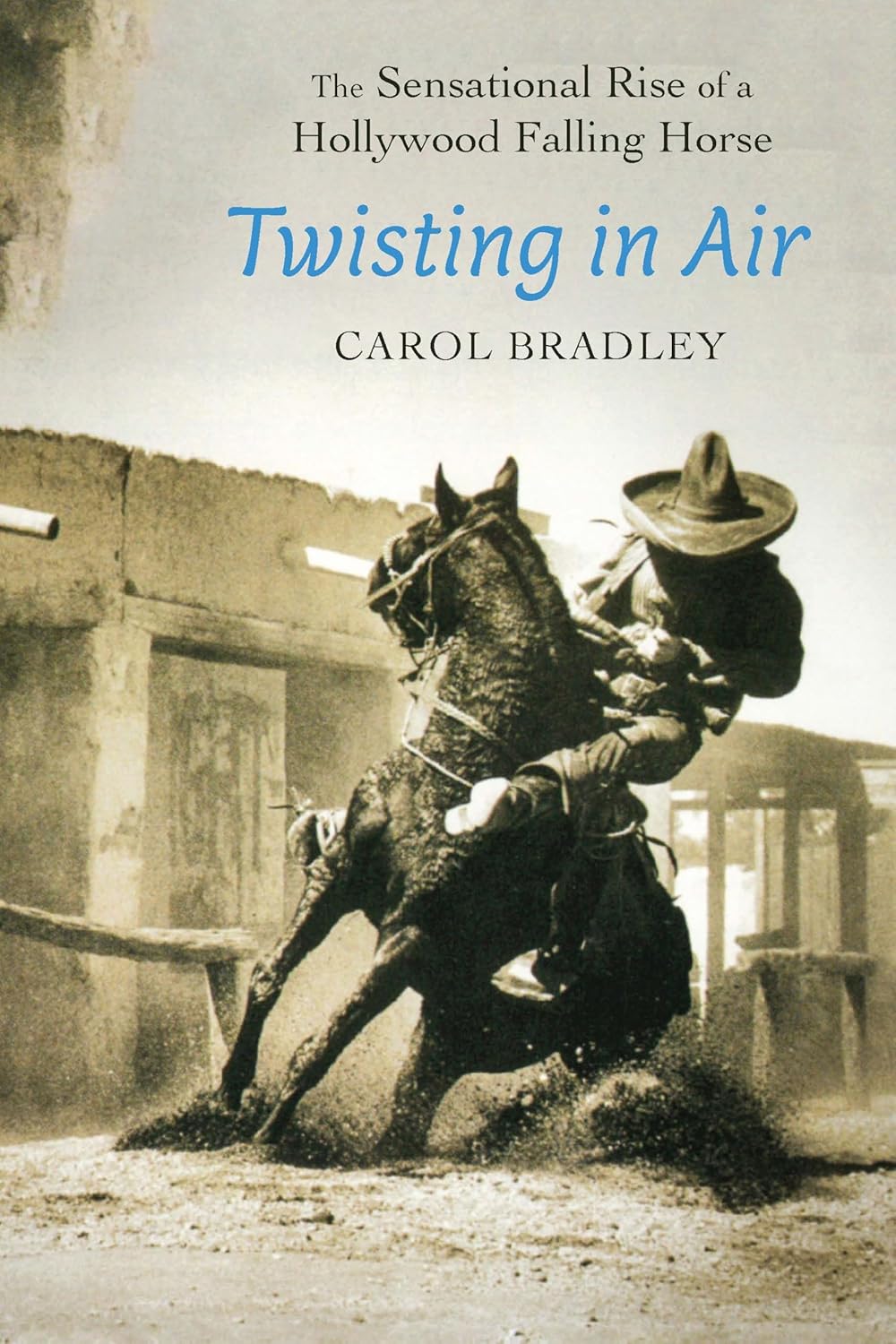

A scintillating, sickening look at how we used to treat movie mounts.

The first real American movie, “The Great Train Robbery,” released in 1903, was only 12 minutes long, but it ushered in a stampede of fans of the Western. It featured Bronco Billy, who would appear in 400 cowboy movies even though his horse skills went no further than being able to sit on one without falling off. It fell to Hollywood’s next cowboy star, William S. Hart, to show the film world real equestrian prowess.

To accomplish this, Hart needed an equine co-star. He found one in the fearless Fritz, a puny pinto gelding. Fritz bravely jumped through a plate-glass window (before Tinseltown used spun sugar to substitute for the real thing) with Hart on his back and, in 1917, became a star in “The Narrow Trail” by tip-hoofing across a fallen tree over a steep canyon. Fritz was listed in the credits and received thousands of fan letters, many with sugar cubes in the envelopes. Hart was so loyal to Fritz that when the horse was supposed to fall off a cliff in 1924’s “Singer Jim McKee,” the actor insisted the stunt be performed by a mechanical horse painted to look like Fritz. The horse’s fans were outraged because they thought it was real.

Carol Bradley’s delightful Twisting in Air is a gallop through Old Hollywood filled with fun anecdotes about cowboys and the horses who loved them, as well as a serious examination of animal cruelty — and the largely lame efforts to combat it — in the movie world.

There have been many talented hoofers. Early movie cowboy Tom Mix had Tony, who could untie Mix’s hands and even had his own stunt horse, Buster, who performed feats deemed too dangerous for Tony himself. The horse’s fan mail, addressed to “Just Tony, somewhere in the USA,” managed to reach him. Gene Autry’s horse, Champion, could smile and dance the hula. And Roy Rogers’ Trigger, pen in his mouth, signed the guestbook with an “X” in the lobby of New York’s Hotel Astor in 1944.

But it wasn’t all sugar cubes for Hollywood’s equine stars. The work was dangerous, and the methods for extracting Oscar-worthy performances from animals were cruel. During the filming of the infamous chariot race for the 1925 silent classic “Ben-Hur,” almost 150 horses were wounded and a half-dozen killed. Recalled actor Francis X. Bushman, who played the evil Messala:

“There were wrecks every day in the chariot races. When the horses were hurt, they were not treated by a veterinarian but simply shot.”

To get horses to fall, a trip wire was tied to their front legs and threaded up to a ring on the saddle, which the stunt rider controlled. As the horse galloped, the rider pulled on the ring, and the animal’s hooves went out from under it. Horses could — and did — break their legs or necks as a result.

As many as 125 horses were hobbled by trip wires in “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” the 1936 movie starring Errol Flynn. Some had to be euthanized. Three years later, in “Jesse James,” a horse outfitted with blinders and a trip wire was forced to jump off a cliff — the height of a six-and-a-half-story building — into a river. In the film, the beast (a horse double) happily swims toward shore; the diving horse actually drowned. The American Humane Association (AHA) subsequently launched a national advertising campaign showing stills of the dive with the headline, “Nobody’s Going to Pull a Stunt Like This Again.” In 1940, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America banned distribution of any movie that used trip wires. Soon thereafter, AHA representatives were allowed on set to monitor the practice.

Consequently, a new profession emerged for man and beast: training a horse to fall naturally and finding animals talented enough to do it. Trained horses eventually fell all over Westerns — there were as many as 25-30 talented stunt-horses in constant demand. Falling on command was an old skill — Napoleon’s army trained its mounts to fall so soldiers could use them as shields to hide from the enemy. In Hollywood, trainers made falling as palatable as possible for all involved: Stirrups were made of rubber, and horses practiced falling on sawdust. The AHA had no objection to the practice.

Other safety improvements were implemented, too. Horses now burst through doors made of balsa wood and, in “The Hallelujah Trail,” Lee Remick jabbed a lazy horse with what looked like a hatpin but was really dried spaghetti. Sandstorms were recreated with powder to avoid scratching the eyes of the talent — stuntman and beast. During gunfights, horses’ ears were stuffed with cotton.

Still, there were microaggressions; stunt horses’ coats were dyed to mirror the equine stars they played. And (in a much more serious aggression) John Wayne once punched a movie horse between the eyes after the animal bit him on the butt. Occasionally, a horse rebelled. Television’s “talking” horse, Mr. Ed, could answer a phone, untie knots, open doors, and pick up a pencil. Yet when he grew tired from working too long under the klieg lights, he froze in place and refused further commands to perform.

Charming as it is, Bradley’s book doesn’t shy away from the scandalous history of Hollywood’s mistreatment of animals. Although the AHA mandated that horses be limited to two falls a day, it inexplicably allowed veterinarians to drug animals. (Smokey, Lee Marvin’s horse in “Cat Ballou,” was drugged to look like he was sleeping in one scene.) With the demise of the studio system and the Hollywood Production Code, the rule requiring AHA representatives to be on set was relaxed. Away from their watchful eyes, the trip wire returned with a vengeance.

In the late 1970s, a bill was introduced in the California legislature to criminalize the mistreatment of movie animals. Macho movie cowboy Glenn Ford testified in its favor. “I’ve been in 187 films and…the animals desperately need this protection,” he said. The bill failed. Subsequently, Michael Cimino’s 1980 movie, “Heaven’s Gate,” was rumored to have been an exercise in horse carnage; trip wires were rampant, five horses allegedly were killed in falls, and one was blown up with dynamite. The AHA called for a boycott, but it need not have bothered. The film was a huge flop.

The silver lining was that it prodded the Screen Actors Guild and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers to agree to allow AHA inspectors back on movie sets. But if you looked this gift horse of an agreement in the mouth, it clearly had no teeth. Trip wires weren’t banned, and there were no penalties for filmmakers who continued to use them or refused to open their sets to inspectors in the first place. Today, responsible filmmakers follow AHA guidelines, but perhaps the greatest gift to horse safety is that moviegoers have long since moved on from Westerns.

Diane Kiesel is a former judge of the Supreme Court of New York. Her next book, When Charlie Met Joan: The Tragedy of the Chaplin Trials and the Failings of American Law, will be published in February by the University of Michigan Press.