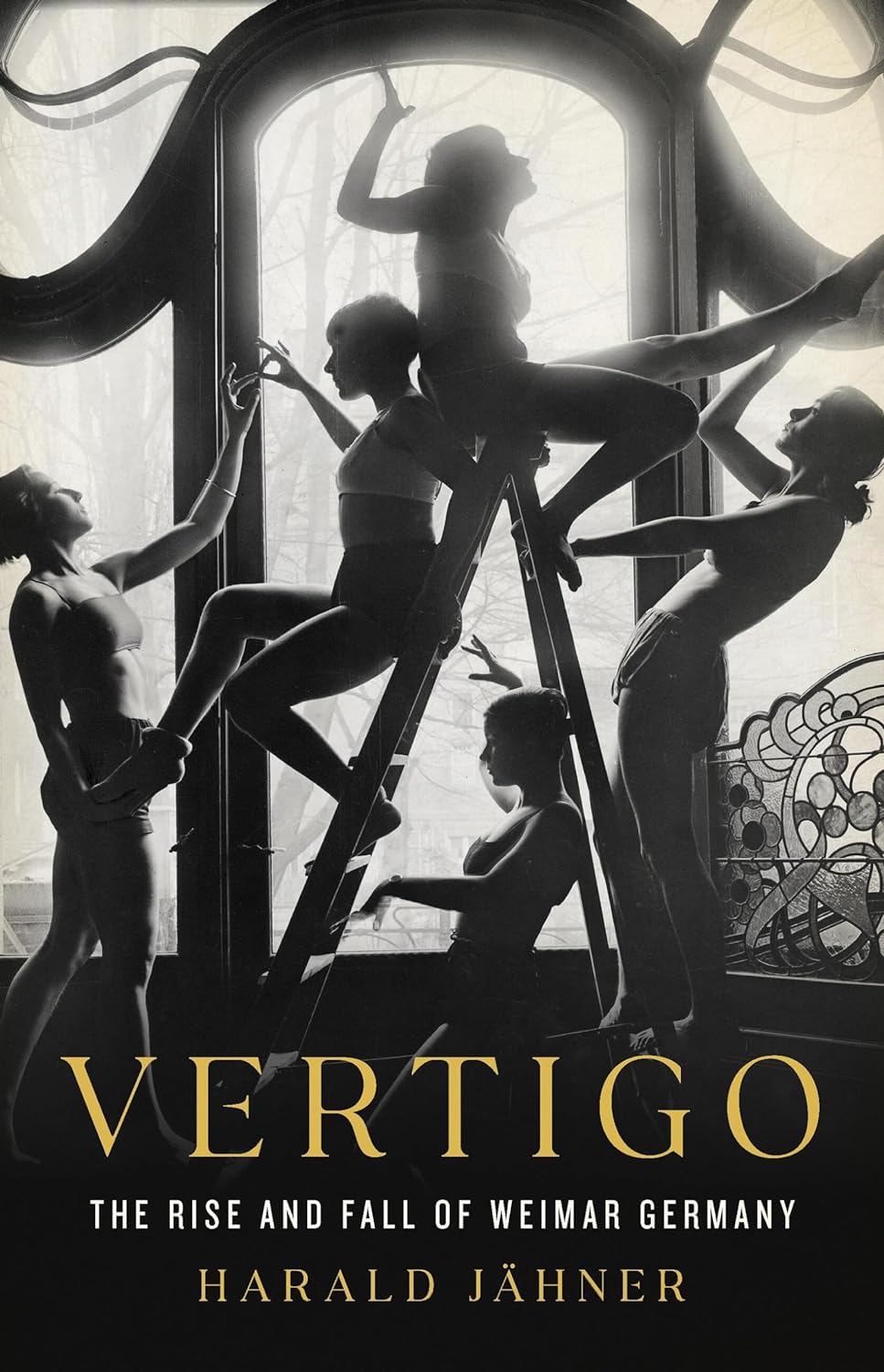

Vertigo: The Rise and Fall of Weimar Germany

- By Harald Jähner

- Basic Books

- 480 pp.

- Reviewed by Mariko Hewer

- September 11, 2024

An illuminating look at a lesser-examined yet pivotal period.

The brief Weimar Republic (1918-1933) is often given short shrift in coverage of 20th-century German history, wedged as it was between the monarchy of Wilhelm II and the emergence of the Third Reich. In the meticulously researched yet accessible Vertigo: The Rise and Fall of Weimar Germany, cultural journalist Harald Jähner seeks to remedy this, providing both a portrait of a surprisingly carefree time and chilling insights into the ascendance of Adolf Hitler and Nazism.

Germany’s loss in World War I consisted, as the author explains, of compounding traumas. First, the combat itself:

“Fighting was no longer carried out face to face; the enemy was invisible across no-man’s land, their covered position being held with a hail of shells from a great distance. The two fronts held one another in place, while the troops dug themselves into their trenches and tried to send each other mad with endless drumfire. A shift of the frontlines by only a few metres cost countless thousands of human lives, all of them consumed as cannon fodder.”

Then came the conquered soldiers’ return home. Men who’d fought for the German monarchy were told no such institution existed any longer. The country’s new leader, Friedrich Ebert, tried to placate them with meaningless platitudes. Writes Jähner:

“‘No enemy has vanquished you,’ Ebert declared, before immediately continuing: ‘It was only when the enemy’s superior power in terms of men and material became increasingly oppressive that we gave up the fight.’”

Little wonder veterans joined armed bands of roving criminals answerable to no one, and that civilians, battered by Treaty of Versailles-mandated reparations and inflation, adopted an “anything goes” attitude. This feeling permeated many facets of life, from architecture (“Art deco flirted with the world of opium and cocaine, and presented itself as a drug in built form”) to dancing (“The Charleston was an encouraging dance. It fired up the ego and encouraged people to express their own emotions through dance”). It even seeped into the realm of gender relations (“Some particularly extravagant women also borrowed the symbols of mature men: the top hat, the walking stick and finally the monocle”).

While these years of openness and devil-may-care experimentation provided innumerable people with opportunities to which they’d never before had access, the republic’s frequently changing political goals, coupled with rising joblessness and lingering feelings of humiliating defeat, created a vacuum into which the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), better known as the Nazis, seamlessly stepped. Explains Jähner:

“In Braunschweig, in October 1931, the NSDAP demonstrated that it was seeking power outside of parliament. The party bussed in tens of thousands of uniformed men from across the whole of the country for an SA [Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party] torchlit process through the little town. After that they ran rampage through the medieval working-class district to intimidate its residents, two of whom were fatally injured in the street battles.”

Sound familiar?

That the Nazis’ poll numbers continued to rise so steadily testified to Germans’ exhaustion with the current government’s inability to steer the ship of state. Indeed, Hitler’s appointment as chancellor was at first intended to sap him of power. “What if he [President Paul von Hindenburg] gritted his teeth and accepted Hitler as chancellor,” poses Jähner, “with [former chancellor Franz von] Papen as vice-chancellor, as a kind of counterweight?”

History, of course, shows that Papen was devastatingly ineffective at this task; Hitler and his allies succeeded in quickly consolidating their power and were brutally open about their plans. Recounts the author:

“[I]n February 1931, Joseph Goebbels had declared to the Reichstag that adhering to the Constitution was only a temporary, tactical manoeuvre…‘According to the Constitution we are committed to the legality of the way, but not the legality of the goal. We want to conquer power legally. But what we do with that power once we possess it is up to us.’”

Goebbels’ words too closely echo certain modern-day leaders’ rhetoric for anybody to be at ease. Harald Jähner has given us in Vertigo a blueprint for the growth of fascism. Will the world be canny enough to avoid traveling down that road again?

Mariko Hewer is a freelance editor and writer. She is passionate about good books, good food, and good company. Find her occasional insights at @hapahaiku.