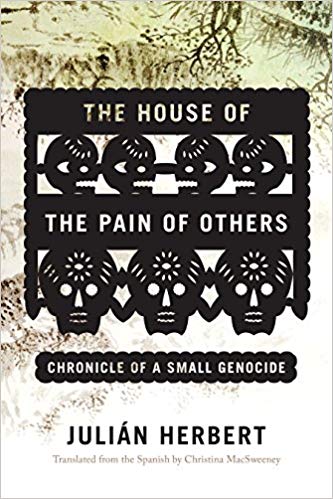

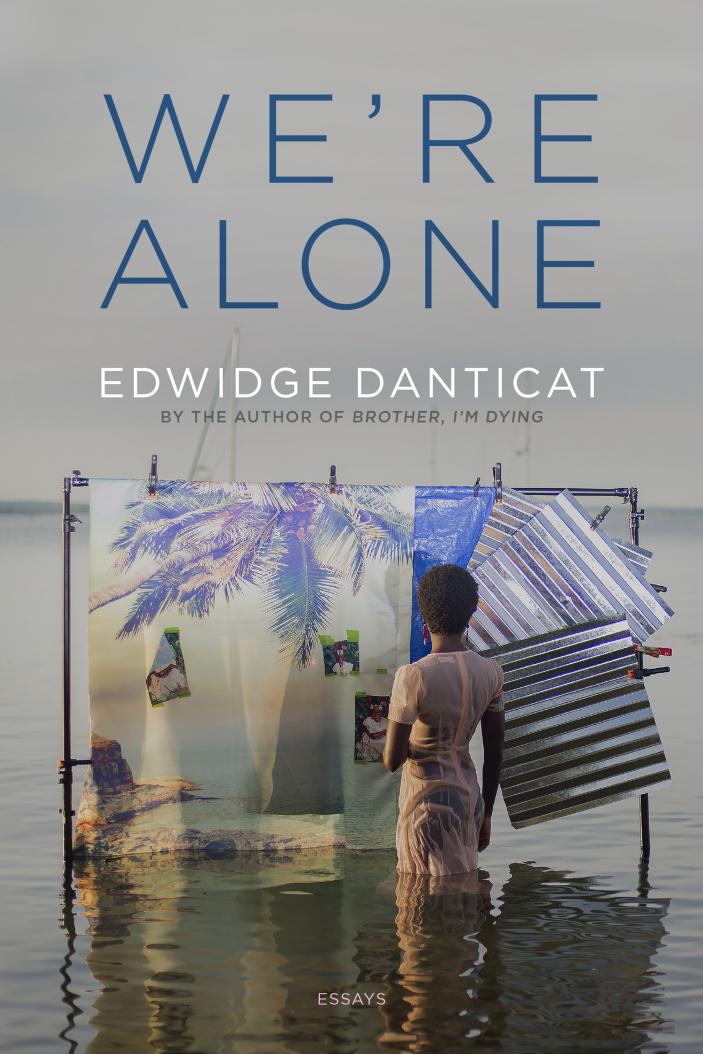

We’re Alone: Essays

- By Edwidge Danticat

- Graywolf Press

- 192 pp.

- Reviewed by Jennifer Bort Yacovissi

- September 24, 2024

The author’s conversational tone belies the rage felt on behalf of her Haitian homeland.

In a bizarre convergence, We’re Alone, Haitian American Edwidge Danticat’s slender new essay collection, came out exactly a week before the Republican candidate for president — in front of a debate audience of 67 million — accused a community of Haitian immigrants in Ohio of stealing and eating pets. The resulting firestorm of vitriol and threats of physical harm against those Haitians, called forth by our former president and chief hatemonger, is a torch illuminating much of Danticat’s thematic landscape.

Her book’s title can be read in a few different ways, as she discusses in her preface. It could mean that each of us — however much we may be in community with one another — is ultimately isolated even from those we love. Perhaps, on the other hand, it’s the intimate acknowledgement of lovers (or of writers and their readers) finally alone together. Or, possibly, it’s that we are, as a collective, on our own. As the saying goes, “No one is coming to save us.” We must do it ourselves.

Given the historical abuse, pillage, and general catastrophe inflicted by outsiders on Danticat’s home country — and onto members of its diaspora — it is this final interpretation that feels most apt. Danticat speaks here as though chatting with friends: warm, accessible, but also vibrating with a controlled rage that doesn’t need to be fully articulated because friends understand and share it.

A compelling storyteller, Danticat weaves multiple threads through her essays of family, of separation and reunion, of Haitian culture and history, of writers and writing, and of calamities past, present, and yet to come. She recalls her response when students in a workshop asked who taught her to write:

“My best writing teachers were the storytellers of my childhood, I told them. Most never went to school and never learned to read and write, but they carried stories like treasures inside of them. In my mother’s absence, my aunts and grandmothers told me stories in the evenings when the lights went out during blackouts, while they were doing my hair, or while I was doing their hair.”

In the collection’s first wide-ranging essay, “Children of the Sea,” which includes memories of a family vacation in Haiti that was initially bucolic but later overshadowed by danger and despair, Danticat summarizes in a single page-long paragraph the brutalization of the country through the centuries. It’s a history U.S. readers are likely unfamiliar with but in which America is roundly indicted. Later essays fill in more details.

“By the Time You Read This,” which foregrounds the communal nature of Haitian mourning rituals that covid so painfully interrupted, becomes an abbreviated roll call of Black immigrants abused or killed by mobs or police: Eleanor Bumpurs, Yusuf K. Hawkins, Abner Louima (a Danticat family friend), Amadou Diallo, Patrick Dorismond, Sean Bell. “Some Black immigrant parents harbor the illusion that if their émigré and U.S.-born children are the politest, the best dressed, and the hardest working in school, they might somehow escape incidents like this,” writes Danticat. Instead, they are forever tormented by “the hypervigilance required to live and love, work and play, travel and pray in a Black body.”

She doesn’t shy away from discussing the violence in Haiti, but it’s hard to miss how the combination of centuries of colonizers’ abuse and interference — including the U.S.-backed overthrow of Haiti’s democratically elected president in 1991 — along with the devastation of earthquakes and intensifying hurricanes, contribute to a hopelessness that breeds a “take what you can” nihilism. As a young man guarding an impromptu roadblock tells Danticat and her family, “We want a future, but they keep snatching it away.”

“They Are Waiting in the Hills” is a more joyful discussion that surveys Danticat’s communion with various authors she has either known personally or been influenced by. “Writing the Self and Others” offers an intimate look into her own family, which has been deeply affected by long-term geographic separations. And yet, as she quotes her mother, “the journey continues.”

Finally, just to square the insane Republican conspiracy circle, in “A Rainbow in the Sky,” Danticat describes speaking at a rally after Hurricane Matthew in 2016, demanding that the Department of Homeland Security extend the temporary protected status (TPS) of Haitians that had been granted after a cataclysmic 2010 earthquake. TPS is the legal status of the Haitians living in Springfield, Ohio, the status even the Trump administration agreed to extend, albeit in six-month increments.

The journey continues, indeed.

Jennifer Bort Yacovissi’s debut novel, Up the Hill to Home, tells the story of four generations of a family in Washington, DC, from the Civil War to the Great Depression. Her short fiction has appeared in Gargoyle and Pen-in-Hand. Jenny reviews regularly for the Independent and serves on its board of directors as president. She has served as chair or program director of the Washington Writers Conference since 2017, and for several recent years was president of the Annapolis chapter of the Maryland Writers’ Association. Stop by Jenny’s website for a collection of her reviews and columns, and follow her on Twitter/X at @jbyacovissi.