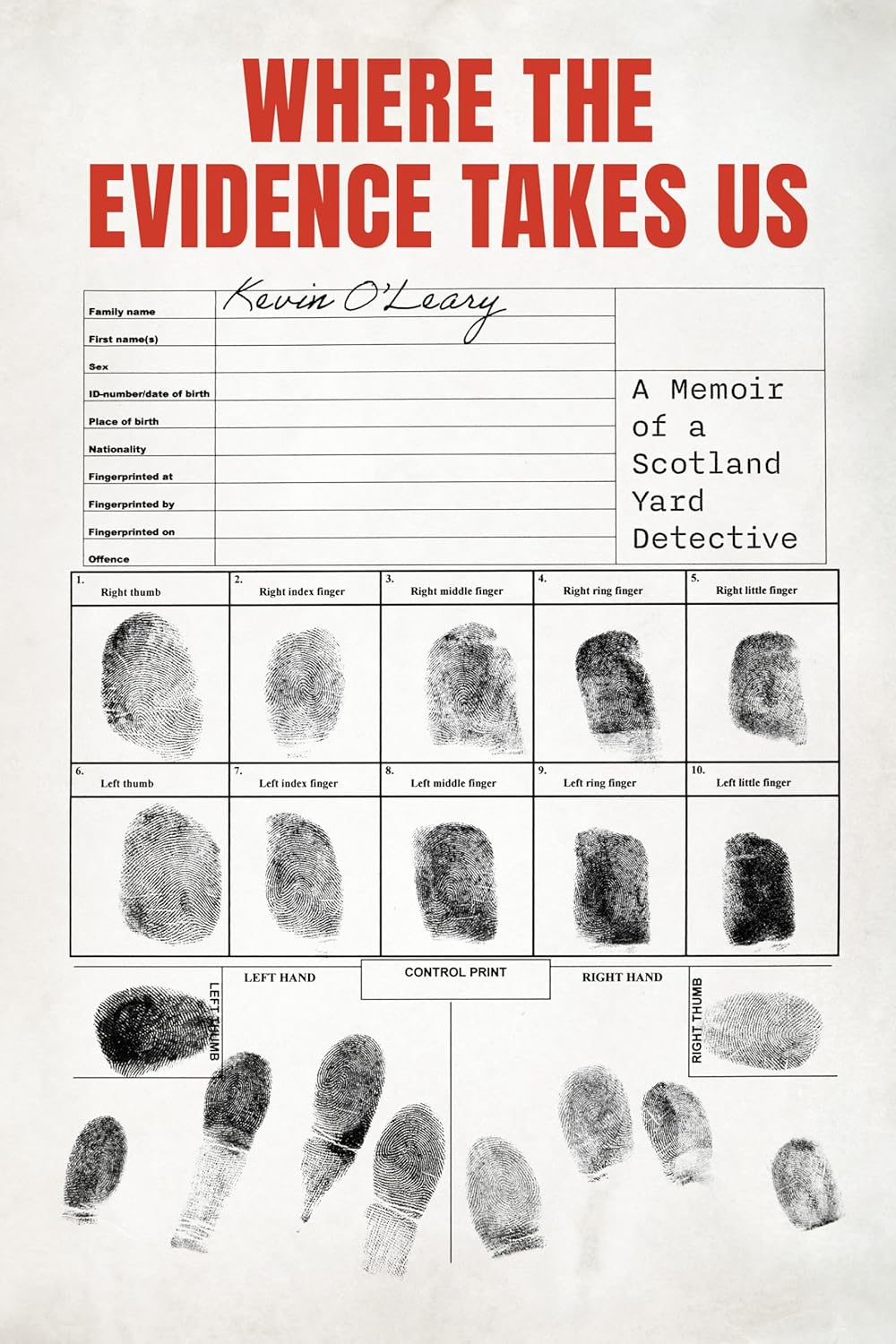

Where the Evidence Takes Us: A Memoir of a Scotland Yard Detective

- By Kevin O’Leary

- Rowman & Littlefield

- 282 pp.

- Reviewed by Art Taylor

- December 31, 2024

An uneven, sometimes insightful reflection from a former lawman.

In the reviewing course I teach at George Mason University, I assign as reading an interview from the Washington Review of the Arts with book critic Doris Grumbach. “I try to enter into the book as a thing in itself,” Grumbach says in the piece, “to see how that particular thing the author set himself to do works.” She advises approaching each book “in a state of what can only be described as innocence…you want to be emptied of your preferences, your prejudices, your past.”

In the first paragraph of Where the Evidence Takes Us, Kevin O’Leary explains the title of his book with a passage that echoes Grumbach’s words. After pointing to “confirmation bias” as “toxic to survival” for the police, O’Leary quotes a phrase detectives use in press briefings: “We’re keeping an open mind, and we’ll go where the evidence takes us.” As he explains, “More than impartiality, [this phrase] signals a journey of exploration and discovery that describes events that shaped my career.”

That opening — along with the author’s bio and the book’s description — shaped my own expectations of O’Leary’s work, and I kept returning to the title and the complications of confirmation bias as my reading journey progressed (haltingly, it’s worth emphasizing). If innocence is the ideal state in which to approach a new book, then some jury might well find me guilty, since I struggled frequently to reconcile my personal preferences with the book at hand.

O’Leary is a former senior detective at New Scotland Yard, and among the milestones of his career are heading up the Yard’s Covert Operations Unit and supervising security for the London Olympics in 2012 (and, more recently, serving as a consultant for the British TV series “Hunted” and “The Heist”). Between the blurbs and the marketing description on his memoir’s cover, I was anticipating “a front-row seat to the pulse-quickening realities of policing,” “a mirror reflecting the evolving landscape of policing and society at large,” and “an insider’s perspective on the challenges, triumphs, and transformations that shaped an era.”

Ultimately, O’Leary does deliver on much of this — increasingly as the book progresses and perhaps with greatest focus and clarity in the epilogue. The chapters on SO10 (the Specialists Operations designation for undercover work), on hostage negotiations, on the Olympics and the Notting Hill Carnival, and on Operation Peyzac (an undercover effort to get guns off the streets) are particularly insightful.

For example, O’Leary talks in broad terms about the shift in covert tactics after the late 1990s Human Rights Act and Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act and explores the phrase “Lawfully Audacious,” an approach that uses “all methods available…to fight crime, including those that took us to the very edge of our legal powers.” But he also recounts — in sometimes harrowing detail — specific missions using decoy officers, who set themselves up to potentially be assaulted in order to “spare future victims from the ordeal.”

Along the way, O’Leary provides perspectives on interagency collaborations (or competition) and on the role of politicians in police matters — the latter not often flatteringly:

“At the risk of being cynical, the announcement of an investigation gives politicians the opportunity to appear outraged and accountable while simultaneously shifting responsibility away from themselves.”

To his credit, O’Leary is keenly attuned to shifts in policing ethics and in societal expectations of policework, particularly as related to race and gender. He discusses his own work trying to increase diversity in the ranks of undercover officers (an uphill battle) and reviews the Stephen Lawrence inquiry from 1993, prompted by the police’s unsatisfactory investigation of the racially motivated murder of an 18-year-old Black man. Though O’Leary wasn’t involved in the case, he remembers “the shared sense of professional shame in an institution I was proud to be a part of that was now described [as] institutionally racist.” He reflects later:

“There were difficult times for the police service following the Stephen Lawrence inquiry, but if any good came of the tragedy it was the professionalization of training, responses to critical incidents, and investigations into murder and other serious crimes.”

A full chapter is devoted to violence against women and girls — “A woman is killed by a man every three days. Domestic abuse makes up 18 percent of all recorded crime in England and Wales” — detailing undercover operations to catch sexual predators and even looking at cases of abuse by police themselves. O’Leary reflects as well in the chapter “Negotiation” about men’s struggles with traditional roles and expectations, noting the fact that men “remain almost three times more likely to die by suicide than women” and gesturing toward both existential philosophy (Camus) and the nature of language (e.g., “man up” as a common phrase, and “fortify” as a useful alternative).

But if the second half of the book delivers thoughtful perspectives, the first half was where I wrestled with my expectations. The narrative here stretches well before O’Leary’s Scotland Yard days, and those early sections often seem more focused on amusing anecdotes than important insights: the listing of pranks for “naïve rookies,” for instance, and the idiosyncrasies of squad cars, which featured bells instead of sirens — “comical when used…The policy wonks missed that one” — until the mid-1990s. Even recollections of serious episodes — such as the Broadwater Farm Riot of 1985 — dwell on the in-the-moment melee at the expense of broader perspectives about policing unrest.

All too often, the narrative’s balance felt off. Stories pile on top of one another, sprawling anecdotes overwhelm the chapters they appear in, and funny asides lead to ill-placed interruptions. The image that kept popping to my mind in those passages was of a veteran cop at a pub, sharing war stories over a pint, reminiscing about “the folklore of the bad old days” (O’Leary’s phrase), always with a punchline or quip at the ready, and usually with an exclamation point for emphasis:

“This was a department shooting itself in the foot!”

“You should’ve seen their faces!”

“Piss taker!”

“Thanks Deb and Tony for keeping a secret. You’ll never make it as a spy, either of you!”

So, was my investigation of Where the Evidence Takes Us compromised by my own preferences and prejudices? The gravity of O’Leary’s résumé, combined with the promises of the book’s jacket, led me to expect seriousness and depth from start to finish, and an honest look not only at policing’s psychology, sociology, and philosophy, but also at its humor and humanity. As the now-retired O’Leary reflects in the epilogue, “I don’t miss the circus, but I do miss the clowns.”

In assessing his memoir, I hope I’ve made a clear case — both for and against the book — by going where the evidence took me.

Art Taylor is the author of The Adventure of the Castle Thief and Other Expeditions and Indiscretions. He’s a professor of English and creative writing at George Mason University.