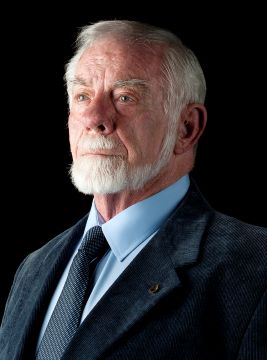

Recalling Tom Stoppard’s longtime bond with composer André Previn.

Tom Stoppard and André Previn were an odd couple and also collaborators and best friends. Playwright Stoppard, who passed away last week, was the first to admit he knew nothing about music, couldn’t even read a note. André, the musical polymath — conductor, classical composer, jazz pianist, scorer of 50+ films — was not a writer, though he did publish a slim book about his Hollywood years.

But as they became friends, André told him, “If you ever need a symphony orchestra for one of your plays, I’ve got one.” Or, as Stoppard recalled, “One day, he said we should try to do something together. I said yes, that might be a good idea. But it took a few years.”

They would, indeed, work together on two productions. They weren’t Rodgers and Hammerstein, but their common ground was enough to produce “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour” in Britain and “Penelope,” an opus posthumous completed after André’s death, in the United States. With words by Stoppard and music by Previn, the latter premiered at Tanglewood in western Massachusetts in July 2019.

These weren’t the best-known or most celebrated of Stoppard’s plays, though. He won five Tonys for others: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Travesties, The Real Thing, The Coast of Utopia trilogy, and, finally, Leopoldstadt, about a Jewish family in Vienna murdered by the Nazis. He also co-wrote the screenplay for the 1998 film “Shakespeare in Love,” earning him an Oscar.

Now, Sir Tom has also passed on, at 88, at his home in Dorset, England. For the biography I’m writing of “Cousin André” (Previn’s grandfather and my great-grandfather were brothers), I interviewed him in August 2023.

It was actress Mia Farrow, the third of André’s five wives, who brought them together. André was conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. Stoppard had translated from Spanish into English a Federico García Lorca play Mia was performing, and they were talking about André. He found André “so fascinating,” Mia said, that he told her, “I could watch him brush his teeth.”

André would come by the theater to pick her up from rehearsals and there met Stoppard. “We used to meet for dinner quite a lot,” Stoppard told me, at the Cafe Royal, just by Piccadilly Circus. “We had these hilarious meals together. And we stayed friends ever after.”

Eventually, what emerged from the friendship was “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour.” The idea for the play came from Stoppard’s own family’s experience escaping Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia. There was another, unspoken subplot that linked the composer and the librettist. Stoppard had Jewish roots, which he did not then know about, but the Holocaust silently shadowed both him and André, whose German-Jewish family had fled Berlin in 1938. Stoppard learned in the 1990s that both his parents were Jewish and that his four grandparents and three aunts had all perished in Nazi death camps.

“I jumped at André Previn’s offer to write such a play,” Stoppard said, “partly out of admiration for him, partly out of secret megalomania — never having been offered 100 musicians before, and partly because as far as we know there is no precedent for the kind of hybrid we [were] attempting.”

He continued:

“We didn’t actually work side by side. I wrote these pages, then I gave them to André, and he wrote the music, and it didn’t mean much to me in the end. I heard the music for the first time when the orchestra was rehearsing. It was like a dancing partner who you didn’t dance with, put together without your having to be there.”

“EGBDF,” as the play was known, also stands for the notes on the treble clef. It told the story of two prisoners sharing a cell in the mental ward of a Leningrad hospital. It premiered on July 1, 1977, with two beds and six actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company and music composed and conducted by André and performed by 80 members of the London Symphony Orchestra.

André tried to bring Stoppard into his musical world, inviting him and his then wife to a concert. “It was the first time I’d ever been to an orchestra,” Stoppard told me. “It had very little effect on me. It didn’t turn into a habit. I have no idea what the orchestra played that evening. The only thing I recall, which I’ll never forget, is that when the lights were low, the maestro walked onto the podium. He just glanced up toward where we were sitting to check out that we’d picked up our seats. It struck me as completely amazing. My blood ran cold.”

Returning the favor years later, Stoppard invited André and Mia’s adopted daughter Daisy — he was her godfather — to be his date on opening night of a Broadway show. “He waited outside the theater,” Mia said. “He rang me next morning and said, ‘Daisy stood me up.’ Everybody in the theater community would’ve loved to be with him that evening.”

André and Stoppard’s second collaboration, the hybrid work “Penelope,” occurred three decades later, when André was well into his 80s and in declining health. This time, the collaboration also included diva soprano Renée Fleming, who’d long wanted to premiere a new work by André.

“Periodically, for ten years or more,” Stoppard said, “André would nag me about would I do something for Reneé Fleming to sing. I didn’t know how to write for a singer. In the end, he said, ‘Just write as if it’s a monologue in a play.’”

Stoppard tried to think of a female character he could write such a piece for, and “in the end, Penelope from The Odyssey appealed to me,” and to André, as well. He and Previn “liked the same things; when it came to the literal word, we had very similar tastes,” but, oddly, they could never talk about composers.

Based on Homer’s epic poem, the production’s main character, Penelope, was the wife of Odysseus, who was busy battling the Trojans while she waited patiently for his return. In his absence, she turned away many suitors and remained faithful by knitting and then repeatedly unraveling a shawl she said she must finish before considering other options.

Fleming, in the title role, would sing the arias André composed. She and other collaborators who’d long known and worked with him viewed it as perhaps a parting gift to the man they so liked and admired.

“I suggested asking Tom Stoppard to create the libretto,” Fleming told me, “not only because I am such a devoted fan of his work, but also because I knew he and André were great friends. Having two such creators working together would create tremendous interest from presenters and the public.”

When Stoppard was in New York, Fleming said, “he would host these wonderful gatherings of friends and theater celebrities, and I would typically attend with André, who was using a walker then. I was so impressed when we’d get to the club. Tom treated André with respect and affection that was evident to everybody in the room, a kind of recognition that, hey, this is André Previn!”

Stoppard had seemed the obvious choice to write the libretto. What Fleming didn’t know was that he’d never done one before. She just presumed he had because “he’d done many musical settings.” So, the collaboration between the maestro and the librettist ensued, if in a bit of an off-course way.

“For ‘Penelope,’” Fleming said, Stoppard “wrote a beautiful, complete text, but at the length of a spoken one-act play. To set it properly would have created a two-hour piece, and we’d been commissioned to do a much shorter work than that.”

So, they gathered in André’s one-bedroom apartment on East 65th Street. A grand piano commanded center stage in the living room. There were books, CDs, and sheet music everywhere, some piled on top of furniture. “The process was incredibly rewarding,” Fleming said. “To sit in the room in André’s small apartment when he and Tom Stoppard worked together was such a privilege given their brilliance and unique rapport.”

But Stoppard had doubts. “I’d give him pages and wait to see what he’d do at the piano,” he remembered. “I really had no criteria to judge…I was afraid I was very disappointing to him.” Stoppard would send pages from London for André to compose around.

He was close to finishing the music for “Penelope,” Stoppard recalled, and saying he needed only two more weeks. Then, sadly, André died on Feb. 28, 2019, just shy of 90. From his work-in-progress, others were able to complete the score, and the production premiered that summer.

A memorial concert featuring André’s work was planned for the following year, but then came the covid-19 pandemic. Belatedly, an event was held on Sept. 30, 2022, at Carnegie Hall. It was organized by acclaimed violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, the last of André’s wives, for whom he continued to compose after their 2006 divorce. Among the 140 present was Stoppard, who’d been best man at André and Anne-Sophie’s “incredibly romantic” 2002 wedding celebration in Austria. He didn’t speak at the memorial, but he’d come from England, and his presence alone was testament to their long friendship.

This past Monday, soon after his death, Mia offered her assessment of Stoppard and his friendship with André. “He was a prince of a person. The best of the best,” she said. “What a kind man. He couldn’t wait to meet André. They met and caught on like a house afire.”

Eugene L. Meyer, a member of the board of the Independent, is a journalist and author of, among other books, Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army. He is currently writing a biography of his musical polymath cousin, André Previn, and has been featured in the Biographers International Organization’s podcast series.