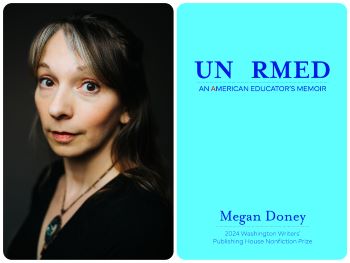

Megan Doney shares the origin story of her debut memoir, Unarmed.

For this column, I interviewed debut author Megan Doney. I know her work intimately because I was part of the team that chose her lyrical, intense, tightly written debut about the aftermath of a community-college shooting, Unarmed: An American Educator’s Memoir, as the second winner of the Washington Writers’ Publishing House’s (WWPH) Nonfiction Prize.

Reading for any contest is hard, but it was especially so for this prize since, as a cooperative, nonprofit literary press that has published poetry and fiction for almost 50 years, we’re only in our second year of publishing nonfiction. I had to ask us all: What makes a work of creative nonfiction one that our press should champion?

With Transplant: A Memoir by Bernardine “Dine” Watson, published in 2023, and now with Unarmed, published this month, I can share that the intersection between the personal and the political, coupled with a voice that leans into storytelling, is what helps this reader/judge decide which works of creative nonfiction the WWPH should publish.

Here is more on the publishing and creative process from a conversation I had with Doney, a professor of English at New River Community College in Virginia.

******

When did you start writing Unarmed? And what was the process like?

I began writing it in earnest in 2015, the year that I was on sabbatical in South Africa. The time and distance were absolutely necessary. I’ve had two agents and been on submission with both. In all cases, the book was rejected largely because editors said they couldn’t sell or market it. Rarely did I receive any actual craft feedback. In October 2023, after the second agent and I parted ways, I decided to send the manuscript to contests and small presses, and that the end of 2023 would be the end of the book. I really needed to be finished with it completely for my own peace. WWPH was one of those small presses accepting un-agented manuscripts!

At the beginning and the end of Unarmed, you write about the Loch Ness Monster. Why does this creature/metaphor have a hold on you?

I love cryptid and monster stories, I love travel, and I am drawn to the possibility, however slim, that mythical, fantastic creatures exist. There are so many enormous human problems that seem unsolvable. I just want to believe that there might be a path to repair.

In fact, the entire memoir is infused with — and enriched by — literary references, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Greek mythology. How did these inform/influence your writing process?

One of my undergraduate professors from the College of Wooster taught me the line from Tennyson, “I am a part of all that I have met; /Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’ /Gleams that untravell’d world whose margin fades /For ever and forever when I move.” All the other writers whose work I have come back to over my lifetime made me the reader and writer I am. I don’t know how I couldn’t include them.

After the shooting, you immediately returned to teaching at New River Community College in southwest Virginia. Have you ever considered changing professions?

The shooting was on a Friday, and I was back at work the following Wednesday. I did think about leaving both my school and the profession. I interviewed for a position at one of the other community colleges in Virginia but realized that I wanted to run toward something, not just away from it. In his book about PTSD (The Evil Hours), David J. Morris writes, “the impulse to wander, to leave the awful past behind and kill time in a strange place, is written across the lives of so many survivors that it could easily stand as a literary genre all its own.” That was the primary impetus to leave the country for a sabbatical.

You have studied, worked, and traveled in South Africa and are now married to a man you met there, and you weave this into Unarmed. You are upfront about being both an outsider and a white American in South Africa, but how did this influence your writing?

This is a really challenging question. For years, I didn’t publicly write about South Africa at all. I felt that I had no right to an opinion or a thought. I didn’t trust that I could do it any justice. I went there initially in 2007 on a Fulbright Summer Fellowship to study how educational institutions were tackling the massive inequities left by decades of apartheid. After the school shooting at my community college, I returned and studied their Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings and testimonies (held in 1996 and widely televised and viewed) regarding apartheid. Work for an equitable society is far from done in South Africa — or here. However, I do write about this: What if we in the U.S. heard testimonies — televised, prime-time, in front of Congress — from students and teachers and families who had been injured and traumatized in school shootings? Would Americans be moved enough to act?

In the memoir, you explore the personal impact/intersection of gun violence and domestic violence in up-close, intimate ways. What advice do you have for other writers approaching difficult or traumatic subjects?

Many people have asked me if writing the book was therapeutic. I reply that therapy was therapeutic. Writing is another process entirely, one that must include another. I often return to Vivian Gornick and how she distinguishes between the situation and the story. If a writer isn’t sure what the story is or the meaning of the situation, she may need more time to let the situation settle and discern how it dwells now in her life.

Ultimately, Unarmed is a reflective memoir. I appreciate the way you wove in the personal with the political, but this isn’t a hard-charging, activist memoir. You’re not calling readers to a specific mode of action. So, what do you hope they get out of Unarmed?

I frequently hear “I can’t imagine” when I talk about the shooting and what the aftermath has been like. I understand that sentiment, but I think people actually can imagine, they just don’t want to. I hope they are able to realize that this violence does not leave you; there is no getting over it. There is only learning to live in the new reality and [understanding] that no one is safe from it.

*****

Doney, along with our other 2024 winners — Varun Gauri, author of the debut novel For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus, and Chanlee Luu, author of the debut poetry collection The Machine Autocorrects Code to I — will be reading at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda on Sunday, October 27th, at 3 p.m. The event is free and open to all, and a wine-and-cheese reception will follow. Please RSVP here so we know you’re coming. And yes, as co-president of the Washington Writers’ Publishing House, I’ll be there, too. Join us!

Caroline Bock writes stories — from micros to novels. She is the author of the novel The Other Beautiful People, forthcoming from Regal House Publishing in summer 2026. A graduate of Syracuse University, she studied creative writing with Raymond Carver and poetry with Jack Gilbert and Tess Gallagher. In 2011, after a 20-year career as a cable television executive, she earned an MFA in fiction from the City College of New York. She has short fiction forthcoming in the Hopkins Review. She is the co-president and prose editor at the Washington Writers’ Publishing House. She lives in Maryland with her family.