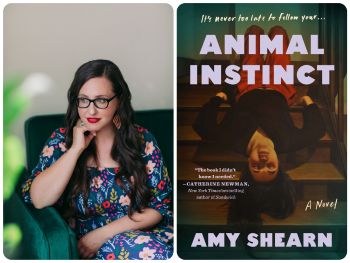

The novelist talks AI, patriarchy, and the frustration of woman-run bake sales.

Brooklyn-based writer Amy Shearn has just published her fifth novel, Animal Instinct, a romp of a tale that follows recently divorced 40-something Rachel Bloomstein as she re-enters the singles world and attempts to navigate dating apps, sexts, confusing algorithms, and a difficult ex, all while trapped at home with her three children during the stress and isolation of the pandemic’s early days.

Shearn’s body of work has been labeled “darkly funny,” “witty,” and “spot-on regarding social commentary,” and Animal Instinct is all those things. Yet it’s also layered with complex questions that explore female intimacy and desire, as well as deeper issues surrounding female autonomy and self-determination.

Back in 2020, before most of us understood the broad reach of artificial intelligence, you conceptualized Animal Instinct, which involves a woman who Frankensteins an AI chatbot to be her perfect partner. Did you see that reality coming — since AI boyfriends are now here, and AI robot partners are around the corner — or was this a random sci-fi thing you thought might occur in the far-off future?

It’s weird, right? When I was writing the book, I was thinking about how much we invite tech into our personal lives, and what the various implications of that might be for our emotional states. I had no idea ChatGPT and AI boyfriends and the like were so close to becoming as mainstream as they have. It felt much more like science fiction. But I was aware of how chatbots were developing to become more interesting to interact with and intuitive to use.

During covid, everybody said, “Don’t write about the pandemic. Nobody is going to want to read about it afterward.” Yet, you dove straight into that period. Why?

I always try to ignore that kind of voice when I’m writing — I write with a reader in mind, not a hater. Otherwise, I would never be able to write anything! That said, I definitely tried to avoid the pandemic at first. In my earliest drafts, I tried to write the book without a pandemic in it, because, right, who would want to read about that? But I quickly realized that Rachel’s actions and motivations didn’t make as much sense without the backdrop of the pandemic — part of what makes her feel so urgently that she has to live her life and be a little wild is that pandemic-era sense that the walls were closing in and that death was imminent. I also really did want to write about how locked-down life was affecting people’s relationships. It seemed too fascinating not to explore on the page.

We’ve come a long way from “Diary of a Mad Housewife” in that women no longer feel captive to their marriages…or have we? Midway through the novel, Rachel admits she felt obligated to have sex with her husband to “ensure someone pays the bills.” How is it that some 60 years after second-wave feminism, women still feel trapped by marriage and subsumed by their husbands and kids?

I have a couple of theories — one is that it’s simply the patriarchy, which is bad for everyone. Not to sound like Andrea Dworkin, but it does seem that some of the patterns of the patriarchy find their way into even the most well-meaning straight relationships unless both parties are very awake, reflective, and open to communication, processing, and change.

Another theory is that men and women are out of sync on this matter. I feel like Gen X marriages in particular have been a kind of crucible of mismatched expectations — often, women my age have gone into marriage assuming they can “have it all,” including an equitable partnership, but men our age are still imagining their marriage will be like their parents’ was. Something like 70 percent of divorces are initiated by women, and therapists, divorce lawyers, and sociologists everywhere have been like, “Well, of course, marriage is very good for men.” Married men live longer, have healthier lives, more successful careers, and so on, while there are so many statistics about how married women and especially married mothers do more work, more housework, more emotional labor, than single or unmarried women.

We live in a country without systemic supports for parents, and as the pandemic laid bare, so many of our existing systems only work because of the unpaid labor of mothers. All my hackles rise when I see a PTA bake sale at a school trying to raise money for something really basic like a graduation celebration run — always! — by women, most of whom have intense careers [outside] of the home, too.

This is your fifth published novel since 2008. What advice do you have for those writers on the “one novel in 10 years” plan who might like to go a little faster?

On one hand, there’s never any rush. Books take time. That said, I also work with a lot of writers who have devised ingenious strategies for getting in their own way. Everyone is busy, everyone is tired. But if you want to write, you make time for it. You might have to give some things up — like staying up-to-date on the latest TV shows, or leisurely weekends — but everything costs something.

Writing in a void is challenging. If you have trouble staying motivated, find some community that can help with accountability, whether that’s a writing workshop, a writing group, or a book coach. Make it a regular part of your life. There’s always something more urgent, but you owe it to yourself to let your writing be important.

Diana Friedman’s fiction, articles, and essays have appeared in multiple publications, including Newsweek, the Baltimore Sun, Huffington Post, New Letters, and Whole Earth Review, among others. She is co-editor of Ole Blue Claw, a forthcoming anthology of short stories set in and written by residents of Maryland. Diana also leads writing retreats in the United States and in Spain.