The essayist talks Florida, interconnectedness, and repeatedly being floored by the sunset.

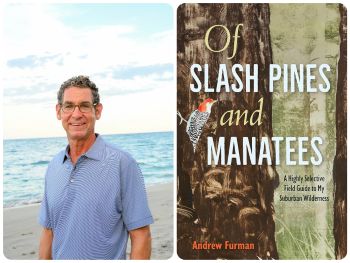

I’ve known Andrew Furman for years, and I’ve just moved to Florida. So, when I saw the announcement for his new collection of Sunshine State essays, Of Slash Pines and Manatees: A Highly Selective Field Guide to My Suburban Wilderness, I knew I’d want to talk to him about it. Andy is an essayist, memoirist, and novelist (his fictional tribute to Thoreau, The World that We Are, will be out in the fall). He’s also a professor of English at Florida Atlantic University, where he teaches American literature and creative writing.

Some of these essays were previously published elsewhere. How did you decide what to include in this “highly selective field guide” to your suburban wilderness?

This book was a long time in the making, almost embarrassingly so as it’s fairly short. I started writing it about 10 years ago, when I found myself trying to grow native plants from seed with my (then) young daughter, mostly to save money on plants. There was something so elemental about this process, learning how to grow coontie and Bahama strongbark and wild coffee and Jamaican caper by seed, which prompted me to want to learn more and more about Florida’s special plants. And then I found myself extending this inquiry to animals, some of them related to these plants. I knew early on that each of the chapters in the book, in the broadest sense, would document my journey coming to know slash pines, say, or sargassum or painted buntings or stingrays or manatees. But I worked on these chapters very sporadically while I simultaneously worked on various fiction projects.

I basically wanted these experiences with Florida plants and animals to occur organically, for me to be inspired by some encounter to prompt my further exploration, both in books and in the field, so to speak. So I just lived my life, doing the outdoors things I love — swimming in the ocean, surfing, birding, walking my dog, fishing — and remained very open to what Florida phenomena came my way. Three manatees, for example, lingered beside my swim pals and me on one of our ocean swims, and I knew almost immediately that I’d be writing a chapter on manatees. Our inshore waters and beaches one season were overrun with seaweed from the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, and suddenly I wanted to learn as much as I could about sargassum. That sort of thing.

An “environmental ethic” is foundational to Of Slash Pines and Manatees. What does that term mean to you? And, at moments, you directly address your readers. What do you hope this collection might motivate them to do?

An “ethic,” as I understand it, is a specific code of behavior shared among a community. I didn’t start off these chapters with a conscious intent to promote any sort of environmental ethic, other than maybe a broad one of greater immersion in and care for the outdoors. Yet, I gradually came to understand that, collectively, these pieces at least tacitly advanced a vision for how we ought to “be” in “place,” essentially that we ought to shed this durable notion that “nature” was something external to us, something separate, say, from “culture.” Rather, we ought to recognize and embrace that we are deeply involved in nature, whether we know it or not, and act accordingly.

Given our climate crisis, it’s folly to deny this interconnectedness. I was inspired, partly, by Mary Oliver’s reflections in her book Owls and Other Fantasies (2003) upon listening to an owl screeching outside her window. “The world where the owl is endlessly hungry and endlessly on the hunt,” Oliver writes, “is the world in which I live too. There is only one world.” To answer your last question here more directly, I hope that this ethic of “radical intermingling,” as I call it in my introduction, encourages readers to seek out experiences with the outside world, wherever it is they happen to live, to undertake their own journeys of homeplace, and that this renewed connection to homeplace will get people thinking and caring more about how they and we ought to live as more responsible fellow citizens of our one world, to recall Oliver once again.

This collection came out in March, and you have a novel coming out in the fall. What’s the relationship between your work as an essayist and your work as a novelist?

This is a tough one, as it’s somewhat mysterious even to me why I turn to fiction in certain instances, regarding certain topics and ideas, and why I write nonfiction in other instances. But what I think I like about fiction is that it allows, even demands, greater room for the imagination. While there’s ample room for a certain aesthetic creativity in nonfiction, you can’t or at least shouldn’t fudge basic facts. In a very real sense, you’re stuck with yourself when you write personal essays or memoirs, whereas fiction allows you to enter into sympathy with other possible selves and scenarios. I probably bounce back and forth between these genres to satisfy both impulses.

At points, you refer to yourself as an “uprooted tree” and “a neighborhood oddball.” How have those sensibilities impacted your writing life over the years?

So, I’ve lived in Florida now for almost 30 years, far longer than I’ve lived anywhere else. Yet, because I bounced around quite a bit in those previous years, I’ve always maintained something of an outsider’s ethos here. What’s nice about this is that I think it’s incited my desire to learn as much as I can about my adopted homeplace in the subtropics. So much about Florida still seems brand new to me. I’m constantly encountering new animals and plants and physical phenomena.

We have such amazing sunsets here, which paint the clouds such interesting colors, and I suppose I ought to be inured to these sunsets by now, but I’m still gobsmacked by these surreal colors. I’m still intensely interested in this place, I suppose I’m saying, which I think more than anything else fuels my writing, that curiosity. It’s something I’ve consciously endeavored to cultivate. I tell my writing students — to the extent that my own writing experiences might be helpful to them — that it’s not absolutely necessary that your life be dramatic or interesting, as long as you’re interested in various things. Figuring out what these things are and pursuing them with enthusiasm and even rigor is the key, I feel, whether you’re writing fiction, nonfiction, or poetry.

Helene Meyers is the author of four books, including, most recently, Movie-Made Jews: An American Tradition. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Lilith Magazine, the Revealer, Chronicle of Higher Education, and many other publications.