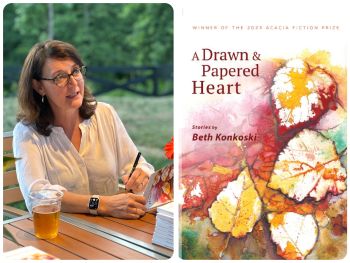

The short-story writer celebrates the one-year anniversary of her debut collection.

Beth Konkoski won the Acadia Fiction Prize for her short-story collection, A Drawn & Papered Heart, which came out one year ago this month. She has also published work in such journals as Story, Smokelong Quarterly, the Baltimore Review, and Split Lip Magazine, and in the anthologies Amazing Graces and Furious Gravity. She lives in Virginia, where she is writing a novel and teaching high school full time.

So many writers are working toward what you’ve accomplished: steadily writing and publishing until you had enough for this masterful collection of 40 stories. What made a difference along the way?

My collection was built over almost 30 years while teaching full time and parenting. Classes at the Writer’s Center, conferences like Conversations and Connections, books like Bird by Bird and The Art of Slow Writing, and, more recently, Zoom workshops and retreats helped me keep at it and feel part of the writing world, even if I published a few times a year. Short stories, flash, and poetry helped because I could finish them, see the results, and pay attention to every sentence I wrote. As a dedicated morning-pages writer, I try to be a beginner every day and enjoy the process. I love getting lost in a piece of writing — no matter the length, genre, topic — so I try to take myself into that feeling as often as possible. People encouraged me along the way: Moira Egan supported my poetry, Richard Peabody accepted work in Gargoyle early on, and Lois Rosenthal edited a “short short” before everyone called it flash and published it as a prizewinner in Story. But if publishing is more enjoyable than writing, you’re in for a frustrating experience. I’ve been lucky to find my way back to the stories themselves, to wondering about how to make a character, a place, reveal itself.

In tackling touchy subjects, did you start with the hot poker, or did it take many drafts to heat up? For example, the cousin in “Sonny Boy,” so damaged by Vietnam, holds a gun to the narrator’s head. Did that action inspire the story or come later?

I often begin with a moment directly from my life or overheard. But these fragments are not stories in full. Years ago, my teacher Kate Besser told me to distinguish between a vignette and a story. This is on my mind when I write, what will elevate the moment to a story, and often that is the heat, the “hot poker” you mentioned. With “Sonny Boy,” Bobby is, in fact, based on my dad’s cousin, who would stop by unexpectedly and drink at our kitchen table. However, I made up the events of the story. That piece required many drafts, especially the ending, because both the young boy and his father have been thrown into such fear and forced into action, yet a sense of empathy for Bobby remains. I wanted that complexity to be present as Bobby is taken away.

There’s a lot of menace in these stories (I looked up “menace” to see if it was rooted in “men,” but “men” comes from “to think,” and “menace” comes from “threat”). “Fifth Grade” opens with Kenny Lustyik and his friends sneaking off to explore the spring ice; and 11-year-old Jill in “Mercy” is brought along on the hunting trip to drive the truck.

I’m drawn to the darker side of human experience, to loss and struggle. I started reading Stephen King in fourth grade, enjoy a book or movie that makes me cry, and see nobility in characters who suffer and sacrifice for others. So, yes, menace does live inside most of my work. Both “Fifth Grade” and “Mercy” are based on my childhood in rural St. Lawrence County, New York, almost Canada, where winter is both long and difficult, and people struggle to make a living. Kids there in the 1970s were not overly protected by adults. My dad read “Mercy” and told everyone it happened almost exactly like I wrote it. And the day Kenny (his real name) drowned is burned in my memory.

To use the language of wine, these stories smell of earth, hay, and marriage, with a hint of the surreal. Talk about writing fantastical pieces like “Witched” and “Retail.”

I love this idea of describing my stories as wine (I actually stopped answering [your question] to write about this in my journal). The surreal feels as true to me as the details of fields and rivers, husbands and wives, the physical truth of my rural upbringing. I never set out to bring those elements into a story; they bubble up as I am writing. For “Witched,” my sister studied Wiccan and gardens, so setting a story at her house, imagining how she would save a sister in need, gave that story its bones. “Retail” was a journal write while on a dinner break from a mall job between teaching gigs. I hated being there, so I wrote about it. Malls are so boring, I let the fantastical take over. I like when stories venture out in unexpected ways, and I’m interested in writers who put fantastical images alongside the ordinary, like George Saunders.

Many of your stories are rooted in the life we know, even as a character is becoming uprooted. In “Cushioned,” Steve thinks, “There is a way to make this work,” about his obsessive attachment to his pillow. And in “Verbs in My Sentences,” Maggie is discovering the depth of Simon’s mental illness. These are stories about the final straw.

I love this description of rooted and uprooted. And, yes, the final straw. Short stories find their heartbeats in the moments a character is going to throw it all in and make a change. There has to be enough backstory to make that believable, and the trick is finding that balance. I talk to my students about the compression of stories we read and tell, how much they can show in dense spaces as we watch characters reach their limits. Of course, in real life, there is the next day, the next meeting, the next horrible decision by those in charge, the next bit of suffering. But there is a delight in watching a character reach the point of no return, taking the plunge into a new way of life. It is hopeful, and a kind of road map, because we do have options to change our lives, to push back against what traps us.

Mary Kay Zuravleff has published four novels, including American Ending, an Oprah Spring Book Pick praised for depicting “a community of Russian immigrants from a century ago in magical, living detail to tell a story that rings true in the present.”