The historian rediscovers a hidden founder of the Underground Railroad and a remarkably human clergyman.

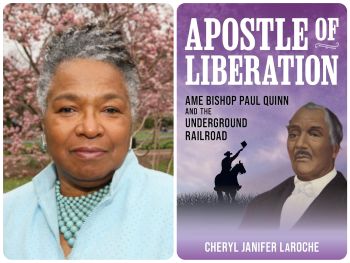

Cheryl Janifer LaRoche’s Apostle of Liberation: AME Bishop Paul Quinn and the Underground Railroad introduces Paul Quinn, a well-known figure in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, founded in 1787. The church still celebrates Quinn as its fourth bishop, its “Apostle of Liberation,” and one of its founding Four Horsemen. At least 40 modern AME churches bear his name, as does Paul Quinn College in Dallas. But through her groundbreaking research, LaRoche also uncovers Quinn’s pivotal role in creating the Underground Railroad to help people escape slavery before and during the Civil War. “I couldn’t understand how someone with that much reach could have been so badly lost to history,” she explains.

Let’s start with Paul Quinn the person. Where was he born?

Quinn was born, I believe, in British Honduras, now Belize, in 1788, to an East African mother and a Spanish father. He came to America as an immigrant, first to Long Island, New York, then settling in Indiana. He’d live into old age until after the Civil War, dying at 85.

His role with the AME Church was unique, yes? Quinn didn’t really fit the stereotype of a bishop, of a churchman.

Quinn was what they called an itinerant preacher, essentially a missionary. He traveled the frontier, mostly alone on horseback, sleeping outdoors, making contact with often-isolated Black communities, bringing the word of God and founding new churches.

Was this dangerous?

Absolutely. Slavery still dominated the country and saw Black churches as a threat. Quinn had to be careful. Kidnappers targeted him. Some of the places he went, the Allegheny Mountains, you just had to be careful. But Quinn was a big man ready to defend himself. Everyone talks about it; 250 pounds before breakfast. He was a boxer before joining the church, known to carry a gun.

As a biographer, I struggled with this duality: a revered bishop, a man of God, yet also a tough, physical man. If you come after him, he is going to defend himself. Otherwise, he never could have accomplished so much. Over time, he developed circuits and networks. He could travel from place to place where people knew him, moving inside of these Black communities.

How many churches do you estimate that Quinn actually established?

At least 42, maybe 50. They cover a wide area: Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, down across to Missouri, then south to Tennessee, Kentucky, even New Orleans. If he doesn’t start the church himself, he sends somebody else, as in California. I’ve documented at least 15 states that he covered, probably more like 17 or 18, plus Canada. All the while, Quinn emphasized literacy, this at a time anti-literacy laws in the South and Black codes in the North and West limited or prohibited Black people from learning to read and write.

How did this church-founding relate to the Underground Railroad?

I first came across this connection while researching my first book, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (2013). The pattern tells the story. Paul Quinn goes into these little Black communities, finds six or eight praying people, and forms them into a congregation. Initially, they’d meet in homes before even building a church. Over time, the routes between these congregations evolved into Underground Railroad routes. Quinn’s fingerprints are everyplace. If you lay out the AME circuits and the Underground Railroad routes, they converge. I proved this in Indiana — I mapped it.

Escape from slavery had been a response since the first Africans captives were brought to the Americas. Quinn gave it structure even before it had a name. The term Underground Railroad didn’t emerge until the 1830s, but the foundation was already there.

Let’s talk craft. How long did it take to research and write this book?

Over 20 years. When researching my first book, I traveled out west into Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and came across all these churches Quinn had founded. It piqued my curiosity. His spirit never left me, so I kept working.

What did you initially know about Quinn? How did you reconstruct his life?

Outside the AME church, little was written about him — just one century-old unpublished sketch, mostly anecdotal. But I kept finding his name in unexpected places. He’s in the news with Andrew Jackson. I did newspaper global searches with his name — which was often misspelled. I looked at genealogy, for instance, to understand Quinn’s first wife. I looked at land records, oral history (authenticating much of what I heard), and maps and made my own maps to track the story. Then the church histories, including small church bulletins. For his time in New York City, I checked city directories, which listed churches in the back, and found newspaper ads Quinn placed for church services.

One newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, that existed for just two years, overlapped with Quinn’s time there — and thank goodness it referenced him. Every time I found one thing, it led to something else. I used all these and more, swept them together into a narrative. It took a lot of detective work.

What was the oddest thing you found about Quinn?

Well, someone had told me that Quinn had found a gold mine, which I first dismissed as a tall tale. But then I found an article about Quinn being robbed of gold. So I checked the land records in Indiana and, yes, Quinn had found gold deposits. He likely had mining experience, possibly back in Belize, so he knew the telltale signs. The mine probably wasn’t very big, but still…This was a surprise.

How does Paul Quinn fit into today’s world?

Quinn was a man of his time — and ours. [Operating] in a hostile political environment — as many of us find ourselves today — he always tried to connect with his community, to grow his network, even outside his denomination. If he found like-minded people, he aligned with them. And he helped build institutions — the Masons, the AME church, the Emigration movement — and worked inside each one to advance the liberation of his people.

Ken Ackerman is a lawyer and author of five major books of Americana, including his most recent, Trotsky in New York 1917: A Radical on the Eve of Revolution.