The writer talks conformity, Flock of Seagulls haircuts, and our aversion to new material.

The last time I saw Elvis Costello, he and his Attractions were opening for Blondie at DC’s Anthem. I guess it was a reunion tour of sorts, since both acts have been around since the 1970s. The audience was filled with people like me, aging music junkies whose college frat parties were anchored by songs like Costello’s “Pump it Up” and Blondie’s “Heart of Glass.”

I wormed my way up to the front. I was here to see Costello, my favorite musician since those days. After he ripped through a string of standbys, he announced that he was going to play some new songs written for the Broadway stage.

“Oh, no,” said the guy next to me. “Come on,” said someone else. “Play ‘Radio, Radio’!” shouted another. For the next three songs, the crowd stood stock still. Nobody sang along.

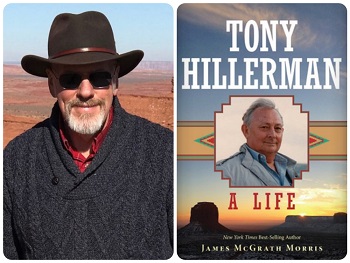

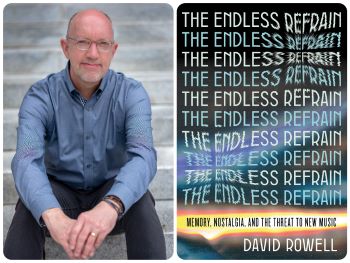

I thought about this concert fail while reading David Rowell’s latest book, The Endless Refrain: Memory, Nostalgia, and the Threat to New Music. In it, the former Washington Post writer (and my beloved editor) explains why the Costello audience — and, by extension, all audiences — might not be so jazzed about hearing new material from our favorite bands, writing, “It’s just that we can’t stop looking to the past for our musical gratification.” It’s why we can’t escape hearing, for example, Crowded House’s “Don’t Dream It’s Over,” released in 1986, at our local Goodwill despite the band’s continual fresh output.

Rowell attributes our musical backslide to a culture that has been driven by conformity and subverted by the ways the internet and media have influenced what we listen to and how we listen to it. It’s a fascinating theory.

What was the catalyst for this book?

Eight years ago, I was with a close friend of mine, Bob Funck, on his run of gigs in New England. Bob had just self-financed a CD of original music, and he had managed to get booked into a bunch of cafes and restaurants that feature live music. At this particular gig, he had played 45 minutes before anyone thought to clap. I found myself really frustrated.

Because it was a three-hour set, Bob had to work in a couple of covers because he didn’t have three hours’ worth of originals. He played Tom Petty’s “You Don’t Know How It Feels,” and for the next four minutes, everyone was just in a kind of rapture because, finally, here was a song they knew. In my notebook, I wrote, “Do we even want new music anymore?” And that question, which I could no longer get out of my head because I felt like I already knew the answer, was the beginning of this book and drove everything that followed.

The book combines personal memoir (we share a similar record collection), reporting (getting to talk to Heart’s Nancy Wilson!), industry research (I love that you phoned the director of operations at your local McDonald’s to get a sense of the logic behind their playlist), and cultural criticism (do we really need to see holograms of Tupac?). What was the most enjoyable part for you to write?

The week I spent with a Journey tribute band in Florida was really special to me. Little moments like when the singer was holding out his Steve Perry wig and lovingly combing it out before he put it on. Or, at one of their gigs at a country club, seeing some members of the catering staff joining the crowd at the edge of the staff as the band kicked into “Don’t Stop Believin’” — those little glimpses of music and humanity really moved me and said so much about the power of music, old or new.

There’s a line early in the book that reads, “We used to want so much from music.” This is such an evocative statement. What do we (as a society) want our music to do for us now?

Honestly, I think that a great many people just want music to take them back to their earlier selves. That’s really one of the biggest arguments in the book — that the music has mostly become a vehicle to take us back to simpler times, before the kids in therapy, the move to a start-up that didn’t, the test results that require more tests. We form the most intense bond with music when we’re teenagers, when everything feels dramatic, and we feel things so intensely. And we tend to not just remember the song that was playing at the food court when Tina said she just wanted to go back to being friends or when Kyle at the homecoming party asked loudly, “Why is everyone bugging?” about his Flock of Seagulls haircut, but those songs really work their way into our system for good because of the moment the music is connected to. Songs inherently make us nostalgic. When we are open to new music, though, I think that we want the same things from it we always wanted: a strong hook, say, a great vocal, a terrific beat. I just think that fewer of us these days are open to forming the kind of relationship to new music that we have with the old music.

More than music, I think, this is a book about aging. What do you think of my thesis?

Ha! I think you’re right about that! It’s about where we find ourselves now vs. where we were in the 20th century; about what remains and what we’re content to let go of; but also about what still gives us joy at this stage of life, whoever you are. The book is using music to explore those issues, but in the end, I do think that what hovers over much of the book is about holding on — or trying to — to who we used to be. And I don’t have any judgment about that. I love old music, too, and I love thinking about what happened to me at other times in my life in relation to that music. But making great discoveries in music has always been one of the most meaningful experiences I know, and I’m trying very hard to keep that true for myself today, too.

Cathy Alter is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and the author, most recently, of CRUSH: Writers Reflect on Love, Longing, and the Power of Their First Celebrity Crush.