The novelist wishes you would learn to pronounce “Oregon” correctly.

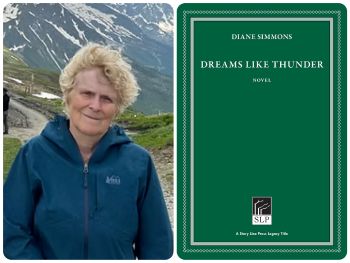

Diane Simmons is the author of the novel The Courtship of Eva Eldridge, critical biographies of Jamaica Kincaid and Maxine Hong Kingston, and the short-story collection Little America, winner of the Ohio University Prize for Short Fiction. Her novel Dreams Like Thunder, originally published in 1992 and based partly on her own relatives, won the Oregon Book Award and has now been reprinted by Red Hen Press. In it, a farm family in mid-20th-century Eastern Oregon grapples with the reality that their way of life is vanishing.

What do you want Easterners to understand about the West from Dreams Like Thunder?

First, I want you people to say OR-uh-gun, not or-uh-GON. And then, we have to define what we mean by the West. The Mountain West is absolutely nothing like the Oregon most people know about. “Portlandia” Portland is wet and mild, lushly green, and wildly liberal. However, Eastern Oregon, where the novel is set, is high, dry, sagebrush desert. The first pioneers passed nearby and kept going. Latecomers like my great-grandfather had little choice but to take up land east of the mountains. There was seldom enough water to go around, and irrigating crops was a constant struggle.

This is one factor that molded those in the Mountain West into rugged, self-reliant conservatives. At least, this is who they were at the time Dreams is set. Easterners need to understand that most of what they have “learned” about the West comes from movies and TV shows And the most popular shows focused on a brief period in the late 19th century of gunslingers and cattle drives. Maybe this limited understanding explains the hilarious rejection of Dreams I got from a New York editor. She wrote that she liked much about the book but she was going to pass because she just didn’t find it “authentic to the West.” No gunslingers, I can only assume.

How do the arguments between main characters Grandma and Uncle Edmund complicate the novel’s portrait of the West?

Grandma and Uncle Edmund are, unknowingly, arguing over two versions of a mythology articulated by writers such as Frederick Jackson Turner and Richard Slotkin. Grandma’s version, similar to that of Turner, portrays the pioneers — her father, Thomas Pratt, for example — as rugged individualists, godly men come to civilize an ungodly country. Uncle Edmund takes up another version of the myth, one seen in Slotkin’s Fatal Environment, that portrays the pioneers as fighters willing to be cruel — even to kill — in order to dominate the new land and extract its riches.

Why is the mythology so important to Grandma and Uncle Edmund? Well, this dry, inhospitable country is rich in mountain beauty, but it doesn’t have much of anything else — just a general store, three churches, and two taverns. There is not much left of the grandeur of the western movement but the myth. And so Grandma and Uncle Edmund both cling to their versions ferociously. This is all they have. It is who they are.

Is the character Alberta, who’s only a child, looking at a dying world, the end of a lifestyle?

In short, yes. In the earliest days, with the Indigenous people driven out and the land wide open, pioneers were able to meet most of their own needs by subsistence farming. They prospered. By the mid-1950s, the trip to Bonner, two days away by team and wagon, could be made by automobile in an hour. People encountered a cash economy. Even if you made most of your clothes, you still longed for the sweaters you saw in stores. Even if most food was homemade, you could not deny the ease of store-bought bread. And even if you made delicious apple and cherry pies, you could not but be tempted by store-bought ice cream. For these things, you needed money, but farming did not supply the cash. The little mountain valley where Dreams is set is no longer sufficient unto itself. The outer world — where it seems life is easier, where you can get a job and a TV set — is now easily accessible, and the valley has begun a steep decline.

Grandma seems determined to keep Uncle Edmund’s wife out of the family graveyard. Why is that so important to her?

When Tom Pratt died, Grandma was a girl of 12, and Uncle Edmund, then 19, partied with his cowboy friends, foolishly squandering Tom’s money and his land. Grandma managed to keep the little farmhouse, the barn, and 80 acres. She married the handsome son of a Cornish miner, and the two of them — with their two children, one of whom was my father — raised chickens, goats, rabbits, cows, sheep, and pigs and had an acre of garden. Money was reserved for essentials such as seed and equipment; there was none for niceties. Grandma made her nightgowns and undergarments from bleached flour sacks; I don’t think she had a store-bought nightgown until Social Security kicked in. So Grandma, having seen Uncle Edmund run through the family wealth, is not about to give him or his wife any more of Tom Pratt’s property, even if it’s only an eight-by-five-foot double plot. Can’t say as I blame her.

John P. Loonam has a Ph.D. in American literature from the City University of New York and taught English in New York City public schools for over 35 years. He has published fiction in various journals and anthologies, and his short plays have been featured by the Mottola Theater Project several times. He is married and the father of two sons; the four have lived in Brooklyn since before it was cool. His first novel, Music the World Makes, will be published by Frayed Edge Press in 2025, while a collection of his short stories, The Price of Their Toys, is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press.