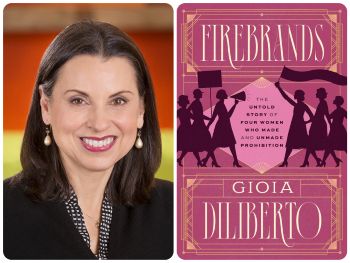

The former journalist talks strong women, Prohibition, and tackling daunting topics.

Gioia Diliberto’s Firebrands: The Untold Story of Four Women Who Made and Unmade Prohibition is notable for many reasons, but one that stands out is its portrayal of the polarization in America around Prohibition. You were either for it or against it, a Wet or a Dry. Diliberto homes in on four riveting figures, two on each side, who were leaders and influencers. Prohibition, it turns out, was a vehicle for many women to enter politics and wield power after they’d finally gotten the right to vote.

How did you get started in your writing life, and what sustains you?

I’ve always been a reader and a writer — ever since I learned to read and write. I started as a newspaper reporter and magazine writer. I look for subjects who, in their personalities, accomplishments, and even flaws, transcend the details of their lives to symbolize the spirit of their time. Toggling back and forth between fiction and nonfiction is a bit like cross-training. I find working in both genres strengthens my craft overall.

My first three books were biographies. My first historical novel, I Am Madame X, in the voice of the subject of John Singer Sargent’s most famous painting, came out in 2003. From there, I wrote two more novels, both about Coco Chanel. The most recent, Coco at the Ritz, came out in 2021. My first Chanel novel, The Collection, is set in her atelier in 1919. In the course of researching it, I learned that Chanel had been arrested towards the end of WWII on charges of collaborating with the Nazis, a story that fascinated me.

How did you come to the subjects of this book?

I was going through copies of Time magazine from the 1920s for another project and discovered a cover featuring a young lawyer named Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who was the assistant U.S. attorney general in charge of enforcing Prohibition. She was just 32 and five years out of law school when President Harding appointed her to go after the bootleggers and gangsters and bring them to justice. Harding, who, with his friends, was a drinker and a hard partier, tapped Mabel because he thought she’d be a pushover. But she was a firebrand!

I wondered what other amazing women were out there whom I hadn’t heard of. So, I looked at Time covers through the early 1930s and discovered Pauline Sabin, who started a grassroots women’s movement that led directly to [the repeal of Prohibition]. She made the cover of Time in 1932. It didn’t take long to realize that Ella Boole, head of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, also belonged in this story. Ella was closely allied with Mabel in fighting to keep Prohibition alive. She was locked in battle with Pauline Sabin to win over the hearts and minds of American women. She was heir to crusaders who’d been fighting to ban liquor since the 19th century and a formidable leader who had the ear of presidents.

During this time, America was divided into two camps — Wets versus Drys. Women were at the center. Women got Prohibition passed, a woman oversaw its enforcement, and a woman got it repealed. This is a story about how women gained a voice in American politics in the immediate aftermath of winning the vote. It was an uphill battle. Although men wanted women’s votes, they didn’t want to give them any power.

Texas Guinan, the fourth firebrand, was the most notorious speakeasy hostess in New York. Tex was a silent-film star who’d made her name in two-reel Westerns playing a badass cowgirl. Tex was just as interested in power as Mabel, Pauline, and Ella. As queen of the speakeasies, she held sway in the murky demimonde where politics, show business, high society, the press, and crime intersected.

Who is your favorite firebrand?

Mabel and Pauline are my favorites because, among other reasons, they are the most interesting and complicated.

What do you recommend for writers beginning to research a topic as daunting as this one?

Read widely on your topic to get a good overview. Then make lists of all the institutions that have primary sources, including letters, diaries, and other documents. I also make lists of people to interview and start contacting them. Research begets more research, and it’s hard to know when to stop! I usually begin writing before I’ve finished researching. That helps me find the holes in my knowledge and where the research feels thin.

What lessons from your book are pertinent to today?

Firebrands highlights a curious cultural phenomenon of today that illustrates the power of self-generated prohibitions as opposed to those imposed by law. Prohibition was a ludicrous idea that glorified alcohol and led to women drinking more than they ever had before. Today, there’s a voluntary new sobriety that’s taken hold across the country, especially among young people under 30. It comes in the wake of a recent World Health Organization announcement that no level of alcohol consumption is safe, and a booming market in nonalcoholic beer, with sales up 35 percent in one year. The most recent surgeon general’s report goes further by recommending that alcoholic beverages carry a warning label like cigarettes do.

The overwhelming majority of Americans loathed Prohibition. One regrettable parallel between the Jazz Age and today is that in the 1920s, as now, Congress was in the grip of a fanatical minority that was too weak and craven to abide by what the majority wanted and to stand up for what was right.

[Editor’s note: Read the Independent’s review of Firebrands here.]

Martha Anne Toll is a novelist and literary and cultural critic. Her debut novel, Three Muses, won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction and was shortlisted for the Gotham Book Prize. Her next novel, Duet for One, will appear in May 2025. Toll has received a wide range of artists’ fellowships and serves on the board of directors of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation.