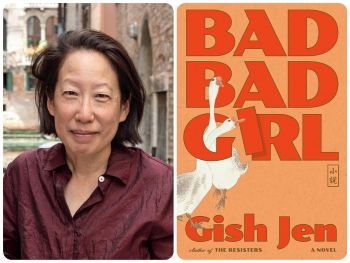

The acclaimed writer untangles her mother’s complicated legacy.

Gish Jen is finally ready to talk about her mother. In Bad Bad Girl, titled for her mother’s recurring scolding, Jen traces a fictionalized version of her mother’s life from childhood to leaving Shanghai as the Chinese Communist Party takes power to immigrating to New York as a graduate student and becoming a wife and a mother. Even as Jen herself becomes an active participant in the story, she demonstrates immense compassion for the complicated woman her mother was.

You write in your author’s note about how this book would’ve been a memoir if you’d had more access to your mother’s life, but instead, “Characters appeared; events shifted; an arc materialized; the narrative made demands.” Can you share a little bit about that process?

There’s very little textual evidence. It’s not like I have diaries or anything like that. My mother would never have kept a diary anyway. I knew that she came [to the U.S.] and I knew that when she came, she had no intention of going home because, as [mentioned] in my book, she changed her birthday. That’s a pretty big thing to do.

Somewhere along the line, she had a boyfriend before my father who was interested in baseball. My mother was a rabid baseball fan, and my father never watched one game, went to one game, talked about any games, and now I realize that’s because it’s all associated with the first boyfriend.

There’s no [real] George Ping. I don’t know this man’s name. I don’t know if he was a Cubs fan. I put [this character] in Chicago because it was more convenient to do it that way. It’s all fictionalized, but there’s a germ of truth in it. The germ of truth is that this first boyfriend was somewhat more assimilated than my father. He was into baseball and he represented something to my mother that I don’t think she ever articulated but I could see in the sheer joy she took in baseball.

What’s different is [that] the textual evidence that I have, I use. The teaching diary is verbatim. That’s my mother’s teaching log, so I do use stuff like that, of course, as fiction writers will. The emotional content is from life, but if you’ve noticed that something has a function in the narrative, that didn’t happen by accident. For example, my own family said almost nothing about what was going on in China. They were clearly very worried about censorship, and they were under a lot of scrutiny. But I had access to some other families’ letters, and they did, so I had a sense of what somebody might say. My own family, I don’t know how they felt.

I had so much historical material to cover. I needed to find an efficient way of conveying what happened, including its effects on people, so you can see me using various devices to do that. That’s why I call it a novel. It’s a novel, but there’s a big kernel of truth in it.

I suspect anyone writing a personal story imagines how their loved ones would butt in. I’m curious to hear what went into deciding where your mom’s voice should appear.

I do not feel that this book is autofiction…but like many [works of] autofiction, it returns to its own origin at the end. This book kind of slides from fiction to nonfiction. I will caution you that even the nonfiction part is not 100 percent nonfiction. But it’s very heavily nonfictional.

I was starting to write things down, processing my mother’s death. I heard her talking to me and correcting me. So it was kind of a natural thing to use that in the book, and in a funny kind of way, even though we mostly [fought], I miss my mother. So much of this book is about trying to understand her. I wish she could come back to life now. I understand so much more and I have a lot of sympathy for her. Through writing my book, I went from being a daughter to being an author. Having turned into that person, I wish that I could see my mother again in real life. She would probably still hate this book. But maybe there might be some small part of her that might think, “Well, that’s all true.”

As you said, you carry a lot of sympathy for your mother. In the book, even when she’s particularly cruel to you, you’re aware of the way her parents were cruel to her, how her life was challenging, and how she’s repeating patterns. How did you balance understanding where she was coming from with validating your own wounds?

That’s what you want to do if you’ve been a writer as long as I have. When we teach writing, we’re talking about craft and point of view, but so much about it is poise. It’s being able to have a certain involvement in what you’re writing and distance. It’s about maintaining that poise and keeping your balance. I can’t really say how you learn to do that, exactly, except that it’s thousands of pages later.

You talk about how you were determined to raise your own children differently, and in the book, one of your children acknowledges that. Was becoming a parent key to you feeling sympathy for your mother?

Absolutely, absolutely. I don’t think you can appreciate how hard it is to raise children until you’ve tried it yourself. It is much, much, much harder than you realize. Having a chance to do it again, or to do it differently, is so healing for me. To have a legacy like this to undo, you know, nobody would have signed up for that. But on the other hand, I feel like I can go to my grave thinking I did at least one good thing — I took this pattern and I stopped it. I have a great relationship with both [my] children.

There’s a lot of ambiguous grief running through the story — your grandparents wishing your mother had been a “number one son,” your parents not being able to see their families, China itself becoming a different country. It feels like something your parents implicitly accept without discussing but something you’re compelled to put words to. It also feels like a Chinese-versus-American divide in some ways. I’d love to hear your thoughts about those two ways of dealing with everything.

I think you put your finger on it that there’s a huge cultural difference. I have a picture of my father standing at what had been his family’s summer garden and is now a hotel. He’s standing there looking at Lake Tai [in Jiangsu province in China], and just looking and remembering and overcome with a sense of loss. This whole world that we loved so much, it’s all gone.

You are correct that he would never have said anything. Those words like, “overcome with the feeling of loss.” Such a sentence would never emanate from my father. We in the West feel that everything must be expressed in words and it’s not completely real unless it is. But actually in the East, they feel that to put things in words is sometimes to cheapen it, and when there’s real emotion, you don’t say anything. It’s very opposite. It’s not that they don’t feel the loss, but their manner of feeling it, it’s different. That’s a big generalization, but the mores are very different. Every culture has its way.

Both ways are largely adaptations to the circumstances that are way larger than any of us. We can only ask ourselves whether, given where we are now, are they adaptive for us now?

[Photo by Basso Cannarsa.]

Anson Tong (she/her) is a writer, photographer, and behavioral scientist based in Chicago. Her work has appeared in Chicago Review of Books, the Rumpus, the Brooklyn Rail, and other publications.