The writer talks displacement, reclaiming our identities, and the literary richness of Kurdistan.

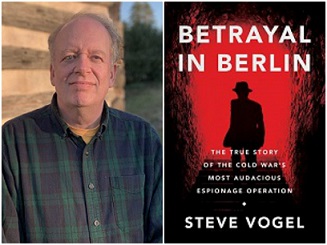

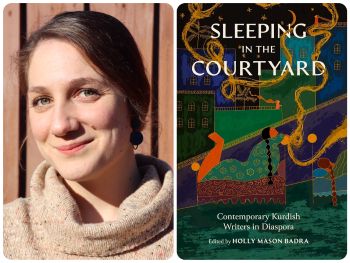

The associate director of Women and Gender Studies at George Mason University, as well as an educator and award-winning poet, Holly Mason Badra is also the editor of Sleeping in the Courtyard: Contemporary Kurdish Writers in Diaspora. Here, Badra — herself of Kurdish descent — explains how the anthology of works by women and nonbinary authors living in Kurdistan and elsewhere came to be.

For many of us, our introduction to “the Kurds” came during the Gulf wars, when the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq was referenced in the news. Obviously, those reports painted an extremely limited picture. What do you hope readers of Sleeping in the Courtyard come to know about the Kurds as a people and Kurdistan as a place?

I’m glad you frame this question with the point of Kurdish exposure connected to war because this was one of the catalysts for the book. It seemed to me that what many in the Western world thought of when thinking of the Kurds and Kurdistan, if at all, was connected to war, devastation, genocide, displacement (or oil). When I started the book in 2019, it was at a time when Kurds were in mainstream media in the West because of Turkey’s attacks on Rojava, and writers were asking me about Kurdish literature in translation. I think it’s a reality that society, writers, and readers often are keen to read more about a culture (and from its writers) when injustice is taking place.

I’m interested in offering a picture of not only Kurdish suffering and grief but also the joy, beauty, delight, and bounty within Kurdish experience. I want readers to be keen to know about our art, our culture, our lives beyond just themes of war and suffering. These themes are important, too, no doubt, but we are more than the valleys and pain. I want readers to see the beauty of Kurdistan’s mountains, gardens, city life, architecture. May they marvel at the landscape. May they shake their head at the state violence that fragments and fractures the region. I want readers to understand the varied, complex, and nuanced lives of Kurds in the region and in diaspora, and especially to gain a fuller picture of Kurdish women’s lives and experiences.

The concept of displacement figures heavily in the anthology. Are there two or three pieces that handle the topic in a particularly affecting way?

In Zhawen Shali’s “A Night with No Country” (translated from Sorani Kurdish by Arash Saleh), the poet explores the vulnerability and silence that accompanies exile. She writes, “inside the jail,/ there existed another jail/ that introduced multiple shadows to my being.” And later, “I had to wear the ice of this experience/ and not burn.” The poem speaks to the isolation and difficulties the poet faced when fleeing Kurdistan and coming to the U.S. for safety, but it also spotlights the incredible perseverance she had to embody to endure such a challenging time.

Maha Hassan’s innovative essay “In Anne Frank’s House” (translated from Arabic by Addie Leak) is another piece that brilliantly explores the topic of displacement through supernatural conversation with Anne Frank. Written while living as a writer-in-residence in Frank’s family home in Amsterdam, Hassan writes, “I fled from a country I’m not even sure I can call mine — though I loved it in spite of the pain it caused — and soon I learned to be good at fleeing. I got used to it. I know you understand me. You were a free spirit who quarreled with everyone. I’m the same. Everything I did was for the sake of my freedom.”

Given that the Kurdish diaspora is so far-flung, how did you set about finding — let alone selecting — the works featured?

I really took a spiderweb approach. I got to know someone who knew someone who knew someone and so on. I did some research online, of course, to find writers, but those results weren’t super fruitful at the time. (Now they would be because Henar Press, a new Kurdish-owned, Kurdish-focused press, has an incredibly comprehensive Kurdish-literature database.) I got to know Kurdish journalists who connected me to writers. It was important to me to get to know the writers first before asking them to join the collection. I really wanted this to be a collection rooted in connectivity, community, and togetherness.

I also really wanted there to be great versatility in style and content to show the rich tapestry of Kurdish women writers. Within the curation process, I aimed to select pieces that offered echoes but also pieces that showed range. That was one of my parameters for decision-making. I also had the opportunity to ask some writers if they’d write specifically for the collection based on what I knew about them and their experiences. I am certain there are other writers who should be in this collection, but I just haven’t had the chance to learn about them yet or to read their work, or perhaps their work isn’t yet translated.

Like many languages, Kurdish has several dialects, including Kurmanji, Sorani, and Badini. Did this make translating and assembling the pieces especially challenging?

One of the things I do lament about the collection is that the Kurdish translations in the book are all from Sorani. I wish we could have showcased translations from other dialects, but this can be quite challenging. Next time, for sure. Farangis Ghaderi, one of the translators in the collection, is doing incredible work to showcase translations from women writers from the less-represented dialects. In future projects, my goal is to be more intentional about showcasing translation from various dialects.

Although your mother is Kurdish, you have a white father and were born and raised in America. Did your Kurdish heritage always figure into your identity, or is it something you had to claim for yourself as an adult?

I love this question! I wish I could say that I grew up with a deep understanding of my Kurdish identity and culture. I think that assimilation maybe took some of that away from us. But I’ve always been proud of being Kurdish even though I didn’t always understand what that meant growing up. I just knew what I knew from my mom and her family, from their stories, from our gatherings. As I got older and understood more about Kurdistan, Kurdish experience and existence, and Kurdish diaspora, I began to understand more of myself and my family’s dynamics.

It’s been through reading Kurdish writers and literature in English that I’ve seen my mom’s stories crystalized and have been able to feel more connected to this piece of myself and my family’s journey/narrative. This is why it’s so important to me to spotlight Kurdish literature. I want others like me to be able to see themselves reflected — and hopefully sooner in their lives. Developing a significant Kurdish community outside of my family has also been super healing and nourishing. It’s been a way that I have been able to claim and reclaim this part of my identity. It’s enhanced my view of Kurdistan and Kurdish experience. A single family will have their own stories, practices, and idiosyncrasies. You’ll see themes and threads, of course, in other Kurdish families as well, but I think it’s important to connect beyond a limited scope.

I found this journal entry I wrote when I was 7 years old after a big family gathering in which I wrote: “We eated dolma it wus good. And the grownup’s played card’s a lot. The grownup’s talk a lot. And the grownup’s played card’s agin.” This is my Kurdish family. My aunts and uncles are more like parents to me, and my cousins are more like siblings. This piece of my Kurdish diasporic experience is a gift.

Beyond your anthology (of course!), where should readers look if they’d like to explore Kurdish authors and poets?

A great resource is the Henar Press database, which is remarkably comprehensive and kept up-to-date. Some other presses that seem to be publishing Kurdish writers and translation regularly are Pinsapo Press, Deep Vellum, Transnational Press London, Archipelago Books, Pluto Press, Comma Press, [and] Afsana Press, and online you can find Kurdish works and translations in Words Without Borders and at Culture Project.

Holly Smith is editor-in-chief of the Independent.