The journalist talks cults and why we keep getting sucked into them.

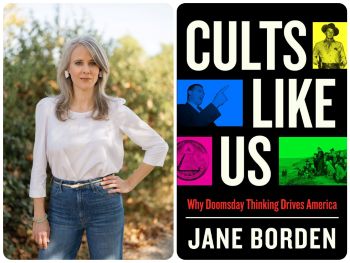

When it comes to falling for cults, the Land of the Free’s track record isn’t the kind of American exceptionalism we should flaunt. In fact, while cults aren’t uniquely American, the U.S. has taken them to unmistakably cruel and dire new levels. In Cults Like Us: Why Doomsday Thinking Drives America, author Jane Borden’s keen insights, excellent research, and healthy dose of gallows humor remind us of who we are — and who we’ve always been.

Talk about the Puritans being America’s first cult. Some may bristle at that depiction.

Yes, I do get some pushback there. I think it’s really just because, at a certain point in history, there was a push to valorize them as the avatars of our nation’s founding, and as a result of that, we’ve kind of swept under the rug some of their more questionable or problematic characteristics. First of all, they were a doomsday group. They believed that the end of the world was coming any day now. Their early Massachusetts Bay minister, John Cotton, said it was going to come shortly after 1655, so some of them were even willing to predict specific dates, and there were other predictions, of course, none of which came true.

Another thing I point to in the book is their obsession with this long-form poem called “The Day of Doom” by Michael Wigglesworth, [which is] basically 200 stanzas of people being damned, being doomed to the lake of fire, begging for mercy, wailing, and crying. This was a culture of punishment and fear. But I ultimately label them a “high control doomsday group.” And we can talk about what defines a cult, but one of the characteristics is that there is a leader who’s worshiped. And so, you know, the Puritans worshiped Jesus.

Now, the ministers, the leaders, the church magistrates, and the Puritan colony especially wielded extreme power, and that power only grew and expanded over time, which is characteristic of high-control groups. For example, they banished dissenters. They were so frustrated with the rabblerousing of [some] that they started executing them. Several Quakers were [hanged]. Residents weren’t allowed to argue with the minister. It was illegal to disagree. People were turned into informants on one another. These are all classic cult tactics.

Is there a unique aspect to American cults compared to the rest of the world’s?

Yes, I believe so. Cults are a human phenomenon. They occur everywhere in the world. I do think they’re more prevalent in America. [However] certain characteristics of cult-like thinking are universal to our species. For example, us-versus-them thinking [is] at the heart of all cult-like thinking. Feeling like a chosen people.

But on top of those, America does have its own flavor, and I think that’s because we inherited certain unique tendencies from the pilgrims and Puritans that are our founding cults, so to speak. For example, the desire for a strongman to rescue us from crisis and punish those we believe have aggrieved us, and that’s the superhero story, that’s Western stories, that’s disaster films. We see that story again and again in pop culture.

Another unique tenet of American cult-like thinking is a tendency to valorize hard work and equate the number in a person’s bank account with their moral character. We worship the wealthy here and we blame the poor for their poverty, the idea being that, well, if you’re poorer, then God has assessed you and deemed you as not worthy.

Most secular cults today are of the self-help variety, and we’re seeing more and more, for example, cults around life coaches and life-coaching. NXIVM was a self-help cult, ultimately. It was also a sex-slave cult. They really checked a lot of boxes in that group: anti-intellectualism, anti-elitism, anti-government sympathies, those are all American and those, of course, have fueled the militia movements, anti-government movements, and separatist cults. I also believe cults proliferate more in America than they do in other parts of the world. Now, that’s not an “always” statement because cult-like thinking waxes and wanes, as [do] upticks in isolated groups.

There have been times in American history where there was…relatively little activity compared to other places in the world. But it’s certainly flaring right now. Participation in cults and the [spike] of cult-like thinking at the societal level both increase during times of crisis…America is facing extreme crisis at the moment [via] technological revolution, social upheaval, and a chronic under-resourcing of the populace.

I don’t mean this in a flippant way, but is there such a thing as a good cult?

The answer is a little bit semantics, but we can go beyond that to say that most cults do have positive aspects to them. Otherwise, no one would join, right? Most cults have a mission to make the world a better place. That’s part of how they attract people. They offer protection. Resources. Some people get a lot out of these groups. And some people get horrifically exploited, right? But the semantics part of it is tough. Psychiatrist Robert J. Lifton came up with a definition because “cult” is a slippery word and it can be sometimes meaningless. And so there’s three characteristics.

There’s a leader who’s worshiped, and the worship part is important. There is undue influence, thought control, thought reform, what we used to call “brainwashing” at play. And then there’s actual harm done. Typically, that’s financial and sexual exploitation of people within the group. So, if that’s the definition of a cult, then it would be hard to say that there is such a thing as a good cult. But you could certainly say that cults have some positive aspects to them. I mean, do all cults go bad?...In my opinion, yes, because since an authoritarian leadership structure is a defining characteristic of a cult, what we see is power corrupting the leader…But, you know, I’m not the first person to say that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

You say you don’t have solutions, but you do have some ideas to improve the situation. What are they?

The first step is recognition, and that’s one of the major goals of my book: to point out our latent indoctrination into these ideologies so we can stop being manipulated by those who trigger them in order to serve their own purposes. Once you see how the magic trick works, you stop falling for it. The second major goal of my book is to help bridge the cultural and political division that is fueling cult-like thinking in our nation. Cults can’t exist without division, without us-versus-them thinking, without there being some kind of perceived, typically manufactured [enemy]…that a certain group of people believes is attacking them.

Another thing we can do…is just to turn toward one another. You know, [it] doesn’t require a government policy or fundraising to bridge division in that way. I often mention a study that was done following World War II. Researchers were looking into certain Gentiles who had helped Jewish people in Germany, trying to figure out what the character profile was of these altruistic people. And they spanned every demographic category. They were rich and poor, they were old and young, it was women and men, educated and uneducated, all of them. The only commonality they found is that each of these altruistic people had been close before the war with a Jewish person. A coworker, a child’s playmate, a teacher, a nanny, something like that. So, you know, familiarity makes hatred impossible.

[Photo by Justin Chung.]

Michael Causey is a frequent contributor to the Independent. He has interviewed authors regularly on radio and in various print publications for decades.