The historian introduces readers to an 1800s lawmaker who deserves wider acclaim.

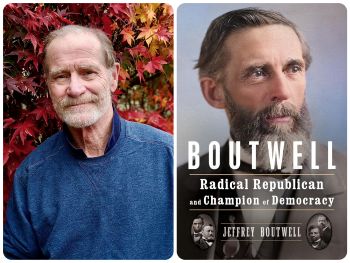

Journalist and historian Jeffrey Boutwell shares a surname with George Boutwell, an important if little-remembered figure from 19th-century politics. In his new book, Boutwell: Radical Republican and Champion of Democracy, he seeks to bring the story of his distant relative to today’s readers, who may empathize with the long-ago politician who left his party when it grew unrecognizable.

Little had been publicly known about George Boutwell until now — hence, the need for this book — but just as little seems to have been known about him in your own family. Why was that?

It’s a mystery I’ll never be able to solve. We were all part of the extended Boutwell family in eastern Massachusetts, but my parents never mentioned George. Nor did my grandfather, yet he was already 17 years old in 1905 when George died and coverage of his funeral took up the entire front page of the Boston newspapers. I guess it was George’s fate to fly beneath the radar. He was a Massachusetts senator, congressman, and governor, worked closely with both Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War and Reconstruction, challenged Teddy Roosevelt’s annexation of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War, and yet no one in our family ever mentioned this illustrious relative.

Given that Boutwell was less prominent than his famous contemporaries, how did you go about finding enough material on him for a full biography?

Well, I shouldn’t complain about family members and historians not paying attention to George, as that essentially gave me first dibs on George’s papers and archives that had been sitting in his former home in Groton, Mass., practically untouched for over a hundred years. The Governor Boutwell House on Main St. in Groton has been the home of the Groton Historical Society since 1933, when his daughter, Georgianna, died and gave it to the society. Since then, the family letters and papers, official documents, memorabilia, and other records have been stored in bankers boxes in a second-floor closet with no climate control, fire protection, or other safeguards. That said, I’m certainly grateful to the historical society and the people of Groton for having preserved George’s legacy all this time.

Do you see echoes of Boutwell — either his ethos or his actions — in any of today’s public figures (political or otherwise)?

George Boutwell believed above all in principle over party. He left the Democratic Party in the 1850s because of its support of slavery, then turned his back on the Republican Party in the early 1900s for what he saw as America trampling the self-determination rights of the people in the Philippines. Though I disagree with her on most political issues, there’s no question that Liz Cheney has exhibited more political courage than anyone today in her fierce criticism of the Donald Trump cult-of-personality that the Republican Party has become.

You’ve said that Boutwell, a Democrat-turned-Republican, considered politics “a civil religion that called for humility, empathy, and a sense of common purpose.” What do you imagine he’d make of 21st-century American politics?

In a word, [he’d be] appalled. Boutwell worked well with both Lincoln and Grant precisely because all three men exhibited “humility, empathy, and a sense of common purpose.” American politics even before Donald Trump arrived with his outsize ego and lack of empathy for others was becoming a zero-sum game. Republicans and Democrats were coming to believe that the other side had to lose, badly, in order for them to win. Nothing could be further from the credo of “a sense of common purpose” that guided Lincoln during the Civil War, Grant during the Reconstruction period, and George Boutwell for his 65 years in politics.

Finally, in the course of your research, did you uncover any other not-quite-prominent figures from the 19th century deserving of their own biographies?

Ambrose Bierce comes to mind. A fascinating writer/journalist/satirist who lived the life he wrote about, especially as a soldier in the Civil War. There have been biographies of Bierce, the most recent being 30 years ago, but he was such a complex and multifaceted figure that I’m sure there’s more to be said. A particular thrill for me was discovering that Bierce mentions George Boutwell in an 1888 column of his for the San Francisco Examiner. For George to be skewered by Bierce in one of his famous “Prattle” columns was, for me anyway, a mark of distinction! Above all, it was exciting for me to “discover” a family member whose story needed to be told.

The flip side of that [in writing my book] was not going overboard in extolling George’s virtues and neglecting his faults, of which he had his share. I’ll be doing a talk next spring in Boston that looks at the challenges of family members writing about their relatives, either near or distant. Also on the panel will be A’Lelia Bundles, discussing her book Joy Goddess: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, and Hester Kaplan, daughter of famed Mark Twain and Walt Whitman biographer Justin Kaplan, which she writes about in Twice Born: Finding My Father in the Margins of Biography. Three very different biographies should produce a fascinating discussion.

[Editor’s note: Jeffrey Boutwell will speak about George Boutwell during the Treasury Historical Association’s Noontime Lecture Series on Wed., Sept. 17th, at the U.S. Treasury Building in Washington, DC. Attendance is via Zoom only; registration is required. Learn more here.]

Holly Smith is editor-in-chief of the Independent.