The novelist reimagines Penelope Fitzgerald’s lost journey.

At the center of Jessica Francis Kane’s fifth book, Fonseca, is a trip that Penelope Fitzgerald never discussed taking. In 1952, she traveled to Mexico, leaving her husband and young daughter at home for three months, while she and her 6-year-old son went in search of a much-needed inheritance from a silver-mine fortune. Fitzgerald left behind few details of what transpired that winter, but from them, Kane has constructed a wondrous tale of revelation and resilience.

Similar to Fonseca, which is your third novel, your first, The Report, deals with historical events. If I remember correctly, you also worked briefly on a novel based on Clara Schumann. Talk about your interest in creating fiction from real life.

I’m surprised to have written two historical novels, to tell you the truth. I never set out with that intention. I’ve been driven by the story, either because it fascinated me (as in the case of Fitzgerald’s trip to Mexico) or because I saw in it something that helped me understand our own time (as in the disaster that is the basis of The Report). I never finished the Schumann book, but your question makes me realize that a lot of the thinking I did for it — around the challenging marriage of Clara and Robert, both musical geniuses — found its way into Fonseca.

Penelope Fitzgerald’s adult children got wind of Fonseca as you were writing it. How did you decide to weave in their letters to you?

I had started writing when I got an email from Terence Dooley, literary executor of the Penelope Fitzgerald estate. He wrote that the family had learned of the novel and wanted to be in touch. I was initially terrified! But as the correspondence developed, I realized what an opportunity it was. Both Tina and Valpy welcomed my questions. At first, I thought the correspondence would just help inform the book, but as time went on, I knew it had to be part of it.

I love the fricative and plosive sounds of “Fonseca.” Fitzgerald traveled to Saltillo in Mexico, but in what appears to be her only attempt at fictionalizing that trip, she calls it Fonseca. Do you have any idea where the name came from?

My theory is that it is a rueful joke to herself about her effort to pursue an inheritance from distant family friends. The word in Latin means “dry well.” She traveled a long way in the hope of securing her family’s financial future, which also might have allowed her to start writing sooner. But she leaves empty-handed and never speaks of the place again. As you said, when she writes of the trip briefly in an essay in 1980, she refers to it only as “Fonseca.”

The storyline of Edward Hopper and his wife, Jo, adds a layer of intrigue to Fonseca. In your research, you learned that their travels to the same area of Mexico overlapped with Fitzgerald’s. I admit to being ignorant of Edward’s discouragement of Jo’s work and utterly disappointed by it, especially after seeing his drawings of her at the Whitney exhibit in 2023. How did you learn about his cruel side, and how do you see it playing thematically with other aspects of Fonseca?

I’m afraid it’s true. I read Gail Levin’s biography and didn’t elaborate beyond what her work suggests. He was a difficult man. He did make unkind caricatures, and Jo’s own artistic career was entirely subsumed by his. When I discovered they were in Saltillo the same winter as Fitzgerald, I was so excited. Fitzgerald was astute about art, and though we don’t know if they met, it seemed plausible. It also allowed me to draw, if you will, a double portrait of the two artistic marriages.

What you invent from fragments of a known story is extraordinary. I don’t want to give too much away, but linking that recorded feeling of being hated to the discovery of a notebook is quite brilliant. I also relished that imaginary bank manager in Fitzgerald’s head. But what completely bowled me over is how you write of Fitzgerald’s noticing that the Lord’s Prayer is missing a verb. Is there a story behind that incredible epiphany? It was certainly an epiphany for me!

That line from her essay about how she and Valpy ultimately left Saltillo empty-handed and “knowing what it was to be hated” fascinated me. Such a strong word for her to use — what could have inspired it? I think people hate most when they’re forced to recognize an uncomfortable truth about themselves. And that’s what writers do, I hope: reveal uncomfortable truths. So, if she started a story in her red notebook about this Irish expat community living off the proceeds of silver mining and colonialism and it was found? That might do it! As for the Lord’s Prayer: Toward the end of her life, Fitzgerald said in an interview that she regretted not being more forthright about her faith in her fiction. She had a lot of faith but very little patience for dogma. The missing verb in the Lord’s Prayer is something I’ve thought about before, so I gave it to her.

A handful of Fitzgerald’s own drawings are included in the novel. What do you make of her habit of creating visual art?

As a non-visual artist, I find it fascinating. I took a drawing class while writing the book so I could understand something of what goes into a drawing practice. Fitzgerald made her own Christmas cards and bookplates for family and friends. Her notebooks are full of little sketches. I was thrilled when my publisher said that Fonseca could begin and end with two of her drawings.

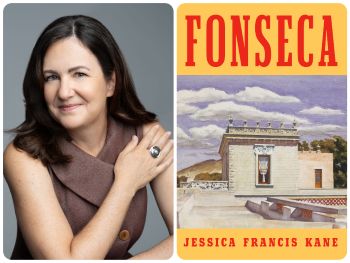

[Photo by Beowulf Sheehan.]

Margaret Hutton is the author of the novel If You Leave. Her work has been published in the Rumpus, the Broad Street Review, the Sun, and other journals.