The prolific writer talks humor, “Psycho,” and backflips into the sea.

I first met John Patrick Higgins three years ago in a cozy Dublin pub, where a handful of writers had gathered for pints of Guinness. He turned out to be a very amusing drinking companion who kept me laughing like a deranged gibbon for two solid hours.

John’s been very busy since then.

His first memoir, Teeth — the story of an Englishman’s quest to transform his blighted mouthful of “lichen spattered tombstones” into a gleaming Hollywood smile — came out in early 2024. His first novel, Fine — a cringe-comedy with a subtly romantic heart — arrived on shelves just seven months later.

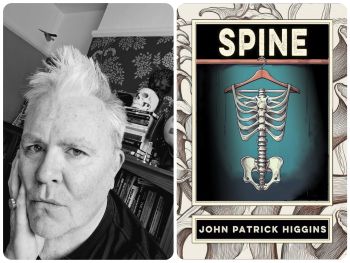

His newest memoir, Spine, opens with the hungover author dragging himself to a physiotherapist appointment, thus launching us into a hilarious, wildly digressive tale of geriatric Pilates classes, car troubles, runaway dogs, and abandoned bottles of urine. John is a wickedly funny writer. Spine is packed with laugh-out-loud moments, and every sentence crackles with wit. But he is also a brave one, willing to reveal his all-too-human life, with its frustrations, humiliations, and heartache.

So, how’s your back?

A constant disappointment.

Fully halfway through Spine, we dive into a long flashback explaining the truly harrowing origins of your back troubles — and, Jesus, it’s not just middle age! Many writers would’ve been tempted to open with that story, but you took us on a far more elliptical path.

Hitchcock’s “Psycho” begins as an examination of Janet Leigh’s quiet, desperate life and the big decision she makes to improve it. Will she get away with her crime, will her boyfriend let her down, does she return the money, and, if she does, will she be blackmailed? Maybe somebody, somewhere, knows everything. It’s perfect, frustrated suspense because we never get an answer. She takes a shower in the Bates Motel, and we’re shunted into a strange and brutal new world.

I want the readers of Spine to have a good time, to be taken on a journey, experiencing a few innocent diversions, so the reveal, when it comes, is a gut punch. Hopefully, you like the hapless idiot you’re spending time with, so the trauma is a proper jolt. Shit gets real, and there’s nothing funny about it. Except I still find ways to make it funny. I can’t help myself.

Your ex-girlfriend Chloe helps you reconstruct the details of that particular medical crisis.

That part of the book takes place 20 years ago, so I thought it might be useful to get Chloe’s perspective. In fact, her recollections matched mine murk for murk. Between us, we managed to weave a tapestry of blurry vagueness that may occasionally and coincidentally nudge reality.

In Teeth, you trace your dental issues to getting brutally mugged. In Spine, you recall the terrible grief that followed your wife Kelly’s early death. And then there’s the household accident that snowballs into a wrenching hospital nightmare. And yet you somehow make us laugh through the worst of it. What’s the connection between comedy and trauma?

The mugging took place in the hallway of my flat. The mugger got away with a bagel and a Kate Bush cassette. I think that’s funny. The lame canard “comedy is tragedy plus time” is often accurate. That’s where the best comedy lives: the pathos, the bathos, the squirming humanity. Comedy comes from people. We’re strange sports of nature, and when we’re not busy being awful to one another, we’re often hysterically funny. I find myself in the peculiar position of being a misanthrope who’s a people person.

Throughout Spine, you’re often cracking jokes with strangers and are generally met with a blank stare. At one point, you remark that a gym trainer “didn’t seem to have a sense of humor at all, something you often find with people who espouse a philosophy of positivity.” Is humor a form of mental illness?

A friend told me she thought I might be suffering from Witzelsucht, a neurological condition in which the sufferer — though, really, everybody else suffers — compulsively cracks jokes. Those are the sort of friends I have — they’d rather diagnose me with a medical condition than admit I made a funny.

I think humor is the mayonnaise in the social sandwich. If you can make someone laugh, it’s the best thing you can do for them, certainly in public. I love the idea that someone, somewhere, is scanning the dots and squiggles pressed into paper that I’ve arranged in a specific order calibrated to make them laugh, and they do laugh. That’s a great, if annoyingly hypothetical, feeling.

In your memoirs, we get an intimate sense of who you are: your razor-sharp wit, your fits of self-loathing, your deep knowledge of pop culture —

That’s who I am alright.

You’re disarmingly willing to share some of your most humiliating experiences. Any regrets?

No, I think I’m fair game. There’s not much point in writing a warts ‘n’ all autobiography, then freezing the warts off with silver nitrate ahead of publication. I’m sure there are things I wouldn’t write about, but the powerlessness, the dependency, and total loss of control are central to the hospital experience. I had an operation to remove my dignity moments after they rolled me through the corridors on a gurney. And that dignity didn’t grow back.

What’s up with the saints? In Teeth, you treat us to a catalog of saints with dental problems, and in Spine, I learned that St. Gemma Galgani is the patron saint of bad backs.

I had a Catholic education, and that stuff sticks to you like wet underwear. I always liked bits of Catholicism. Not the guilt. Not the nosy-parker omniscience. Not the constant tallying of possible moral infringements. Who knows what’s going to offend a superbeing? Anything you might enjoy, apparently. But I loved the smell of the incense, the ritual, the old, echoing buildings. The Old Testament is a blast, and patron saints are always excellent because there’s always a dark irony to how patronage is distributed: Saint Lucy is the patron saint of light because she had her eyes gouged out. She’s also the patron saint of the blind, of salesmen, of throat infections, and writers. I love this stuff.

Your blog is as wonderfully written as your books. What’s the relationship between your blogging practice and your memoirs?

Nebulous. Worrying. Possibly vampiric. The blog tends to bleed into my fiction. It’s a repository of detail, things I might otherwise have forgotten, verisimilitude I can tap into because the details are real, even if the story isn’t.

“The girl on the rock” occupies a place of strange, eerie beauty in Spine. I’m curious about the symbolism of that moment.

Watching a beautiful girl carelessly backflip off a 30-foot rock into the sea is one of the central images of the book. It encapsulates everything foreign to my nature. I’m not brave. I’m brittle and corseted by fear. She had no fear at all. I couldn’t imagine how she went through her day: powerful, self-possessed, un-self-conscious. It was like the end of “Death in Venice”: She was doing cartwheels as I slowly melted in my bath chair. It’s the realization that I was never like that. Even when I was young and beautiful — and I had my moments — I could never have backflipped into the sea. I’d have been worried about messing my hair.

In less than two years, you’ve published three books (with illustrations!), written and directed the films “Goat Songs” and “Muirgen,” and issued two CDs with your band, Ebbing House. You’re making the rest of us look bad. What’s next?

I’m writing a new novel, plus a book about being old, two books of short stories, a musical about giant crabs, and a new film. Also, an album for my band. And I have a novel called How Ghosts Affect Relationships coming out in March of 2027 from Sagging Meniscus Press. There are ghosts in it. As you might reasonably expect. The least I can do.

It sounds like a lot. And it is.

Tyler C. Gore is the author of the award-winning collection of personal essays, My Life of Crime: Essays and Other Entertainments. He has been listed as a “Notable Essayist” by The Best American Essays several times and is the recipient of a Fulbright grant. He was the art director of Literal Latte for several years and currently serves on the editorial boards of Exacting Clam and StatORec. He lives, as he dreams — in Brooklyn.