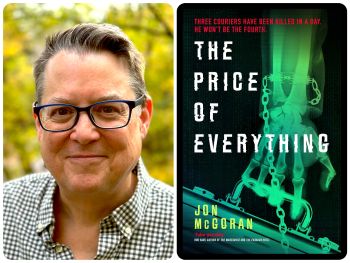

The novelist talks dystopia, our rigged economy, and the pros and cons of MFAs.

With nearly a dozen YA and adult sci-fi thrillers — including the popular Spliced trilogy — to his name, Jon McGoran clearly isn’t afraid to wander down dark, speculative alleys and bring readers along with him. He does it again in his latest novel, The Price of Everything, where the post-internet world he envisions is somehow more menacing than our current one.

When you were writing The Price of Everything, which is described as a “near-future cyberpunk thriller about climate change and corruption,” did you imagine that future would be quite so near as it feels now?

Not quite so much, no. One of the benefits and perils of writing science thrillers and near-future science fiction is that the world can very quickly move closer to or further from the premises of your book, sometimes even between the writing and publication. People often assume that accurately predicting the future is a positive for the book, but it’s a double-edged sword. Current events can make your book incredibly relevant, generating buzz and attracting readers interested in seeing how events might play out. But there are negative aspects, as well. In recent years, as our country and the world have taken some unfortunate turns, the reading public has largely sought more escapist fiction. So, while my books might be extremely relevant, and while there are certainly readers out there who seek out that relevance, the overwhelming buzz in the publishing world is about escapism, with genres like romantasy offering a reprieve or a respite from the constant bombardment of bad news.

On the other hand, if the world leans away from your book, you risk irrelevancy, which could be even worse. Fortunately, I haven’t experienced that with a finished book — although the possibility of it has cost me many hours of sleep — but I and many writers I know have had to discard projects in various stages of completion due to developments in the world, such as the advent of generative AI.

Your protagonist, Armand Pierce, is a courier whose attaché case is literally grafted onto the bones of his wrist. When I read that, my first reaction was, “Wow, how awful.” But my second was, “Yep, sounds about right in this gig economy.” Were you thinking about the plight of any real-life workers when conjuring Pierce’s extreme situation?

Absolutely! Wealth disparity is one of the book’s major themes, and Pierce is a casualty of that — a veteran trying to live in an economy so rigged by the ultra-wealthy that the only work he can find requires him to accept disfigurement for the privilege of risking his life to deliver rich people’s money. Outlandish in a way, but I agree, it is not too dissimilar from the many people forced to do work that is dangerous or unhealthy, whether it’s exploitative gig work, inhumane demands on delivery drivers and others, or even more exploitative labor in other countries — much of it crucial to supply tech for the global rich. With things seemingly getting worse instead of better, it is not hard to imagine things reaching the level depicted in the book. I think it is a pretty devastating indictment that one could look at this and think it sounds about right. But I agree with you — it does.

This isn’t your only novel to feature elements of the dystopian. As an author, how do you balance the inevitable darkness of dystopia with readers’ (particularly YA readers’) understandable desire for something hopeful to cling to?

Without giving too much away, I think The Price of Everything is ultimately an optimistic book, because people fight back against the corrupt forces controlling the world, and in the end, there is hope. Some people like their escapism to be completely different from the world around them, but for me, the best escapism looks at the world as it is or as it is heading — worlds that might leave some feeling hopeless — and explores ways to find hope in that world, ways they can be changed for the better. Especially for young people, but really for everyone, it is important to have hope, to see that change is possible, and to see a future that is worth fighting for.

Counting this new work, you’ve written an impressive 11 novels. How has your approach to writing — including the nuts and bolts of your process — evolved over time and across books?

There are some aspects of my process that have remained unchanged across all of my books, but every story is different, and every book inevitably demands some divergence from the norm. Outlining is always a big part of my process, but even that can vary from book to book. I sometimes have to stop and revise my outlines several times while writing the first draft. On a few books, I have had to write multiple outlines for different aspects of the book — plot, clues, which characters know what.

Perhaps the biggest change in my approach is that I am more able to work on multiple projects at once, to be outline one book while revising another while perhaps ghostwriting a third, and at the same time editing a client’s manuscript and working with students. I am much better able now to go back and forth between all these projects.

As an instructor in Drexel University’s MFA program, you work with a lot of emerging writers. What do you tell them about the value of pursuing an advanced degree in the arts at this moment in time, when our federal government is openly scorning — and outright sabotaging — higher education?

People often ask me about the value of creative-writing degrees and if it makes sense to get one. And the answer is: It depends. There are very clear benefits, the most obvious being the opportunity to learn your craft and benefit from the education and experience of the faculty you’ll be working with. You might not need a degree program to gain that knowledge, but degree programs can help you gain that knowledge more quickly, leapfrogging years of experience, trial, and error.

Another important benefit is the relationships that you establish — with your teachers, but even more so, among your cohort. Sharing experiences and knowledge with people embarking on a similar journey to your own is immensely useful. You do get that from low-residency programs, but probably more so from residential programs. There are more concrete benefits to MFAs, as well, in that many universities require them in order to teach.

But all that said, college and graduate school are not for everyone and are certainly not prerequisites for a successful writing career. And the fact of the matter is, higher education is expensive. Even the more affordable programs are a serious investment, and writing fiction is a tough business, so there is absolutely no guarantee that such expenses would ever be recouped.

I never got an MFA, and I sometimes wonder how having one might have improved my craft, expanded my opportunities, and accelerated my career, but ultimately, that is unknowable.

Holly Smith is editor-in-chief of the Independent and only figuratively chained to her laptop.