The environmentalist decries the perniciousness of plastic.

In 1980, college intern Judith Enck was “thrown into the deep end” lobbying the New York Legislature to adopt a “bottle bill.” The political-science/history major succeeded — on her third try — when her home state passed one of the first beverage-container-deposit laws in 1982.

Enck’s green fervor later landed her a job as an Environmental Protection Agency regional administrator during the Obama administration. Alarm about plastics littering our earth and infiltrating our bodies — the average American generates 220 pounds of plastic waste annually — prompted Enck to launch the advocacy organization Beyond Plastics on Bennington College’s Vermont campus in 2019.

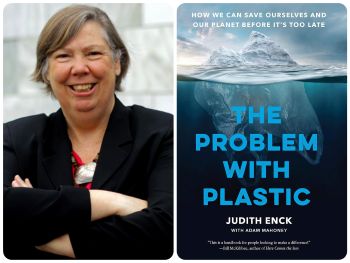

Her new book, The Problem with Plastic: How We Can Save Ourselves and Our Planet Before It’s Too Late, isn’t merely a searing indictment of “pointless plastic.” Its nine chapters lay out practical advice for reducing our daily reliance on it and also provide a how-to guide for everyday people to persuade policymakers to curb plastic production.

Why publish this book now?

There’s an enormous public interest in the growing problem of plastics pollution and not many books about it. It’s very much a cross-cutting issue with climate change, health, and environmental justice. Our book is loaded with footnotes and citations to detail our research.

Chemist Leo Baekeland invented Bakelite, the first fully synthetic plastic, in 1907. When did we become so reliant on these materials?

Use of plastics spread after World War II. Then they became intertwined in the marketing push for a throwaway society. For instance, the message from ads for disposable dishes was about spending less time on housework. But the massive increase in plastics has occurred in the last 10 years since hydrofracking for gas became so dominant. Hydrofracking waste products, called ethane, are heated up and used to make new plastics. The public hasn’t voted for this.

This summer’s collapse of negotiations on a global plastic-pollution treaty, hosted by the United Nations Environment Program, combined with the evisceration of the EPA and other federal agencies, would seem to indicate a grim future for reining in plastic. Where is progress possible?

I was enormously disappointed by the failure of the UN plastics treaty but not surprised. Beyond Plastics focuses on state and local governments, with the great hope that we would eventually tackle national issues. State legislatures are the laboratories of change and innovation, leading the way on climate change and virtually every environmental issue. If anything, we work more at the local level, where we help people stand up for their own community. Plastic pollution concerns everyone, and among the public, there’s bipartisan support for change.

On the climate-change front, the oil and gas industry exceled at pointing the finger back at citizens by telling them to curb their “carbon footprint.” Is the petrochemical industry that manufactures plastic mimicking that blame pattern?

Absolutely, they must have the same PR agency. The narrative we hear from the industry is “Don’t litter and do recycle,” when they well know most plastics are not recyclable.

Should “recycling” and “plastic” even be used in the same sentence?

No. Plastics recycling doesn’t work even though the industry has deceived many into thinking it does. I’m a big supporter of people recycling their paper, cardboard, metal, and glass. Most plastics are not recyclable, the exception being soda bottles and milk jugs marked as No. 1 and No. 2. The plastics-recycling rate is 5 percent to 6 percent, and most of that is beverage bottles with mandatory deposits. Beverage bottles in bottle-bill states are the workhorse of plastics recycling because those containers are kept separate and clean. The limited amount of plastics recycling that happens is called downcycling. Almost all of it is used to create plastic decking, which is problematic when exposed to heat and sunlight because it flakes and becomes microplastics.

Your book is awash with statistics about plastic. Which two are most jarring?

Between the 1970s and 1990s, global plastic production tripled. Every piece of plastic ever produced, unless burned in an incinerator or backyard burn barrel — never a good idea because of pollutants released — is still with us today. It doesn’t degrade. Roughly 40 percent of the plastics produced annually become single-use plastic packaging, mainly for food and beverages. Microplastics from that packaging leach into our food and drinks, so it’s a health issue. We’re laser-focused on that because it’s where we have the greatest opportunity for change. There are so many alternatives.

“Nurdle,” an unfamiliar word from your book, sounds so harmless. Is it?

Nurdles are preproduction plastic. They’re tiny plastic balls, about half the size of a pencil eraser, made at ethane cracker facilities. Mostly, they’re moved by train nationwide to plastic fabricators creating plastic pipes, toys, and flooring. Nurdles are the big sleeper issue because they’re being released all over the country, sometimes from train derailments. This deeply concerns me because spill responses are so inadequate. Every part of our natural environment — soils, rivers, and sediments — are getting a pretty heavy load of these preproduction plastics with a misleading name.

Your book outlines model bills that citizens can customize to tame plastic in their own back yards. Can you describe a victory?

Diane Wilson, a fourth-generation shrimp-boat captain and mother of five in Texas, did what no regulatory agency could do. The (civil) lawsuit she won against Formosa Plastics directed the Thailand-based company to stop discharging nurdles into Matagorda Bay. The largest-ever settlement under the federal Clean Water Act resulted in millions of dollars for community-benefits packages. She’s a force and an inspiring example.

Relatedly, you cite numerous anti-plastics crusaders. Whose story inspires you to fight another day when you need a boost?

Debby Lee Cohen, a mom with two little girls in the New York City public school system, was really concerned when hot food was put directly on polystyrene (Styrofoam) trays at lunchtime and that 800,000 of these trays were thrown out daily. She joined with other parents to convince the school system to stop using the trays. That success led to Debby Lee starting Cafeteria Culture to educate children and reduce plastic use in low-income schools. It inspired her colleague, a talented filmmaker, to make “Microplastic Madness.” When I’m having a discouraging day, I just watch the film’s trailer. The kids are so darn cute. Sadly, she died of cancer last year. Debby Lee was the sort of person you always wanted to be in the same meeting with.

Finally, what’s your advice to the diligent recycler saddled with guilt upon knowing that so much plastic is incinerated or trashed?

Don’t feel guilty because it’s not your fault. But do get politically active. Find friends and neighbors who care and start a Beyond Plastics Local Group; the only requirement is that you have three or more people because you can’t do it alone. You can effect change but you do have to be patient. It takes a very long time.

[Editor’s note: Atlantic editor Vann R. Newkirk II will interview Judith Enck on Wed., Jan. 7th, at 7 p.m., at Politics and Prose at the Wharf, 610 Water St., SW, Washington, DC. Learn more here.]

Elizabeth McGowan, a Pulitzer Prize-winning environmental reporter and author of Outpedaling ‘The Big C’: My Healing Cycle Across America, lives in Washington, DC.