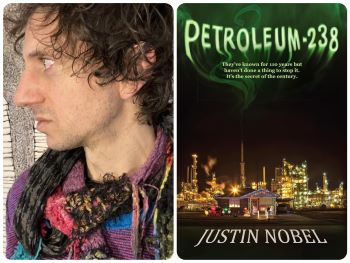

The environmental writer discusses the artistry necessary in covering mass harm.

Award-winning investigative journalist and science writer Justin Nobel has been published in numerous outlets, including Best American Science and Nature Writing and Best American Travel Writing. His new book, Petroleum-238: Big Oil’s Dangerous Secret and the Grassroots Fight to Stop It, grew out of a 2020 piece he wrote for Rolling Stone, “America’s Radioactive Secret.” He discusses the work here.

You have an obvious affinity for frontline workers, activists, and scientists working on issues related to your investigations. Did you have a rural or industrial upbringing?

I was born in New York City. My parents met [as attorneys] at legal aid in New York, and my father went on to work as a public defender. I don’t think I really digested it then, but his work in providing constitutionally mandated legal defense to people who often were in very harrowing situations…became important to the journalism I pursue. Where we lived was not close to horrible environmental issues, [but] I took this amazing environmental science class in high school, and it just goes to show the role of good teachers, because they turn the knobs of your brain in unexpected ways. One of the takeaways [from the class] was that if you don’t live close to the systems that make our energy, you aren’t connected to their harms.

Fracking inverts that in interesting ways [because] it brings industry right to the doorstep of wealthy people in suburbia. It enables people who never really had a close look at industry to stare it right in the face. To report on industry like that, I had to go far beyond the world I knew growing up, to see the parts of America where industry has been allowed to metastasize in concerning ways. That means southern Louisiana and parts of the Ohio River Valley, where a good part of my early reporting took place.

Where do you see yourself on the literary spectrum: more of a dispassionate science journalist or as an activist — somebody who’s helping provide fodder to the legal industry to go after these guys?

[Let’s] say Shell announces they’ll put a new [plastics from gas] “cracker” plant — which they just did — in Western Pennsylvania, and you write it as a journalist from the perspective of, well, “It’ll cost this much, and the state gave this much in subsidies, and these people are against it, and Shell thinks it’ll be great. And we all use plastics.”…In my opinion, [that journalist is] missing the picture. You are what I would call an activist journalist because you’re activating in favor of the corporation. You’re telling their side of the story without really doing what journalists should do, which is digging into the harms that are going to affect the less powerful, the people who will be forced to live next to this thing. And there is quite a lot of science there for us to access. That’s not being an activist. That’s just simply being a journalist. If you’re not doing that, you’re basically doing a propaganda sheet for these companies. I’m just really trying to do my duty as a journalist, carry out our version of the Hippocratic Oath. But in doing that, hopefully, I’ve also made it easier for other journalists to go down these pathways.

There’s a lot of information in your book, and you do a masterful job of making sense of it and making it interesting. What’s your storytelling strategy here?

I think part of why this topic has been difficult to understand is [that the] information completely overwhelms. And when we, as readers, are crushed by information, we turn away. Now, there are fantastic reports on oilfield waste and [related] radioactivity. The information is there in report [and] PowerPoint form. But that’s very different than a narrative in a book. The way I tried to tackle that is by making this book into a journey across America, which is an interesting place. There is beauty, there is talent. There’s a lot to be excited about, and there’s a lot to be concerned about. There are fascinating and unexpected people lifting pieces of this story throughout. That’s something much more exciting than a weighty document on a complex industrial process. I’ve tried to implant [the] energy and excitement that comes with a road trip. There are also funny moments, maybe because it’s so absurd.

I want to ask you about the artistry in the book — for instance, how you depicted a list of Texas water-pollution violations as a river. What led you to take those liberties?

Especially with a [work] that is historical or scientific, the material can get dense. There is a monotony to the eye…There are not a lot of breaks in a science book…But you do have some options, and one thing is to maneuver some of the data in the book in a way that creates a visual break. What you’re referring to are shape poems. [With the illustration of water pollution], it becomes important to know that Texas did know, back in the sixties, that oilfield waste was hugely problematic. I try and bring that to the surface, the names of all the creeks, lakes, and rivers that have been contaminated, and make them into a river, which is, of course, how water moves. You don’t have to read the full list. [For the] reader, the takeaway is, “Wow, there were a lot of instances of contamination!” The initial editor at Simon & Schuster was skeptical and didn’t think it was necessary. But I think it’s fun!

Well, I’m glad Simon & Schuster didn’t prevail. I know you’re doing a lot of work promoting Petroleum-238, but are you also thinking about your next big project?

The work promoting [the book] is still taking up most of my time. There are several different magazine articles, including literary magazine articles, I’m working on connected to the book, and that’s exciting. Pull[ing] the book from Simon & Schuster [and going with independent Karret Press] was absolutely the right move, [but] it’s created a challenge in getting the book out and making sure people see it…There are topics connected to the book that provide a sensible path forward for future work. One is taking this project international. I’ve already spent time reporting on the North Sea. It’s one of the two places where the modern oil and gas industry began. Also, [I’m drawn to] what’s happening off the coast of South America and South Africa, [where] unconventional oil and gas booms are going on right now, affecting the politics. And there are also interesting issues connected to radioactive elements and how they move through the environment and through the body [to which] the reporting has led me.

[Photo by Karen LeBlanc.]

Jim Schulman is executive director of the Alliance for Regional Cooperation, a nonprofit organization fostering sustainable regional economic development.