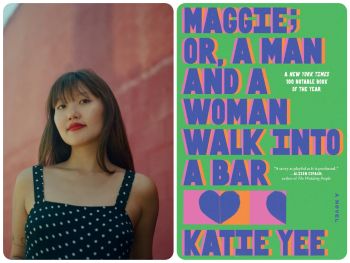

The debut novelist talks humor, cancer, and the incredible weight of names.

Katie Yee’s work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, No Tokens, the Believer, the Washington Square Review, and Triangle House, among other outlets. Maggie; Or, a Man and a Woman Walk into a Bar, her debut novel, was named a New York Times Notable Book and a TIME magazine Must-Read Book of 2025. It tells the story of a woman dealing simultaneously with her husband’s infidelity and her own cancer diagnosis. Yee lives in Brooklyn.

Maggie is suffused with the idea that stories and jokes are not simply entertaining but powerful. How did you come to believe in their power? What made you want to treat such tragic material as comedy?

The bedtime stories and myths are a tribute to the ones my mom and grandmother told me when I was growing up. They’re the reason I wanted to become a writer in the first place; they are a vital part of my own origin story, and I wanted to honor them in these pages.

Writing funny was a new experiment. Before Maggie, I mostly wrote short stories that had bits of magical realism. When I started Maggie, I challenged myself: You’re bound to the rules of this world! No magic! What I reached for, instead, was comedy. They can accomplish similar things: You can’t quite explain how magic works in the way it’s hard to capture why a joke is funny, but they both share this unspoken ability to divide or to bond people.

Trying to write about such heavy topics without humor would’ve been impossible because it’s not how life feels. Writing about [the narrator’s] life as a straight tragedy would be like painting her portrait with one color or writing a ballad with one note. Tragedy and comedy and whatever exists in between are part of every human experience.

I certainly hope you’ve never experienced cancer, and I happen to know you have never been a divorced mother of two. The clichéd advice for young writers is, “Write what you know.” Did you consciously avoid doing that? Was it difficult to find a voice to express major experiences that are not your own?

It’s true that Maggie is far from autofiction. But the point of writing fiction for me is getting to walk around inside someone else’s life for a little while. Breast cancer does run in my family; I’ve watched my grandmother and mom fight it. I’ve been in rooms like the ones I’ve described in Maggie. And, no, I haven’t been divorced but I’ve been heartbroken. And I don’t have kids, but into this narrator I’ve poured all of my anxieties and fears (that they’ll get hurt, that they’ll like my partner better) and hopes and dreams (that they’ll love stories, that they’ll have their own passions and the courage to follow them). Even though the plot of this novel doesn’t follow the plot of my life, I do feel like I wrote what I knew — emotionally? Or at least I wrote what I was curious about, which to me is more interesting.

How do you see Maggie fitting within the burgeoning tradition of Asian American literature?

In school, I wasn’t exposed to a lot of Asian American literature in the core curriculum. It was an optional special-interest class. The books we did read were mostly about immigrating to America, and as someone who is in the second generation, those stories didn’t really reflect my personal experience. Once, I was listening to the writer Sequoia Nagamatsu describe writing about race, and he said that as a member of the third generation, he felt it would be “present but not central” to his stories. That really resonated with me.

Of course, the tradition of Asian American literature isn’t new; we stand on the shoulders of the writers who came before us. Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior was a big influence (see “talk-stories”). It was the first time I had seen something like that written down. Weike Wang’s Chemistry, too, was a patron saint of Maggie. I could go on!

But I feel really grateful to be writing during a time when, perhaps, the broader publishing landscape doesn’t expect all of these stories to look the same, when we can ask more interesting questions. I feel so lucky that there are many fantastic writers being published and recognized and showing what varied shape “Asian American literature” can take.

Can we talk about names in the novel? The narrator reflects on her Chinese name and being forced to choose an American one at school, but she ultimately goes unnamed to the reader. Meanwhile, there is Maggie, a name that carries more weight than we first suspect. Why was it important to handle names this way?

When you name something, you establish ownership of it. Our narrator has a hard time naming her children, and her husband is the one who names them both. When she names her tumor after his lover, that’s her way of taking the reins of her life back. She’s owning her story. She’s reclaiming her own life. But I felt like I didn’t want to lay my own claim to her that way; I wanted her to belong to you (John Loonam) and to you (dear reader) and to whoever else encountered her.

Maggie is your debut novel, and it’s a very impressive start — a major publisher and numerous prominent and rave reviews. Did you anticipate such success? And what comes next?

I don’t think anyone should anticipate success. I think most writers just hope for the best and prepare for the worst. I’ve wanted to be a writer ever since I was 3 years old, but this success is more than I could’ve ever dreamed of. Next up: It’s early days, but I’m working on another novel. It’ll similarly deal with grief and love lost. It’ll probably at least partially take place in the Brooklyn Museum, where I work. It’s a place ripe with stories!

[Photo by Shirley Cai.]

John P. Loonam has a Ph.D. in American literature from the City University of New York and taught English in New York City public schools for over 35 years. He has published fiction in various journals and anthologies, and his short plays have been featured by the Mottola Theater Project several times. He is married and the father of two sons; the four have lived in Brooklyn since before it was cool. His first novel, Music the World Makes, will be published by Frayed Edge Press in 2026, while a collection of his short stories, The Price of Their Toys, is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press this February.