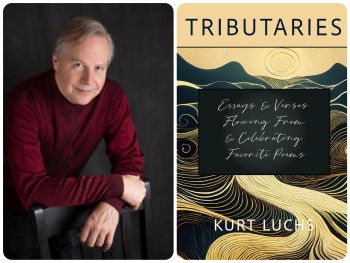

The poet talks humor, ekphrasis, and the work of tribute.

In an age of hackneyed AI, when authenticity itself feels suspect, Kurt Luchs’ new poetry collection, Tributaries, is a breath of fresh air. His prose is lucid, frank, and tender, enlivened by much-needed comic relief. He lays a proverbial wreath at the feet of these “dead poet” poems, offering them loving tribute rather than imitation. His unaffected essays on poetry are paired with ekphrastic codas, creating a dialogue between criticism and creation. The project is radical not through novelty but through return: It reenters the dead-poet catalog to build bridges to the present.

Let’s start with the unique structure of your book. The combination of essays and ekphrastic response poems feels both deliberate and inviting. Can you talk about how you arrived at this format?

Thank you! This project began as a column for my publisher’s quarterly journal, Exacting Clam, which has featured a tribute in nearly every issue since its inception. The structure — pairing an essay with an ekphrastic poem — grew out of my desire to respond to these poets not just as a reader or critic, but as a poet myself. I’m obviously not working on the level of the writers I engage with, but I try to bring everything I have to their work. The poems are meant as an honor to the originals and as a way of showing readers that great poems aren’t only objects of analysis, they can also be catalysts for creativity.

I believe it’s perfectly legitimate for poets to use another poet’s work as a starting point. The goal isn’t imitation but resonance — seeing whether you can arrive at something kindred in spirit using your own voice. If readers follow the book in sequence, they’ll notice that the essays and poems appear in the order they were written. Early on, I directly addressed poets like Wallace Stevens and Robinson Jeffers. Later, I allowed myself to be inspired more loosely. It was very much a learning process. While I’d experimented with ekphrasis before, it wasn’t central to my practice. This project allowed me to explore it more deeply while creating something distinctive for the magazine.

The two-part structure — prose followed by a poem — felt fresh to me. Of course, whenever you try something unusual, there’s the risk it won’t work. But I hoped it would feel useful and inviting, whether for seasoned poets or readers just beginning to explore poetry.

What is it about the ekphrastic method that resonates so deeply with you? How does it inform your creative process?

For me, ekphrasis is an act of gratitude and engagement. It’s a way of responding to art — whether a poem, a painting, or something else — and allowing it to spark new work. In this project, it became a natural extension of how I wanted to honor these poets: by answering them with something personal.

Ekphrastic poems also help demystify poetry. A great poem isn’t an untouchable artifact; it’s a living thing that can inspire further creation. I wanted readers — especially poets — to see these works not as monuments but as prompts.

When I wrote my response to David Ignatow’s “For My Daughter,” the resulting poem became deeply personal. Ignatow’s voice resonated with me as a father of two daughters, and the response felt like a genuine conversation — between his poem, my own life, and the present moment. That’s the power of ekphrasis: It bridges the original work and lived experience.

How does your background as a humorist influence these writings?

Humor writing is merciless. Every word has to earn its place, and that discipline carries over into poetry. Writing comedy taught me precision, clarity, and the value of surprise — whether linguistic, structural, or emotional. Returning to poetry after years in comedy felt liberating. Poetry can hold contradiction: it can be funny and sad, serious and playful, sometimes all at once. I’m comfortable letting a poem begin in humor and turn suddenly earnest, or vice versa. That tonal flexibility feels natural to me.

Humor is also disarming. It lowers defenses and invites readers in. In this book, I use humor not just for laughs but to make poetry feel accessible. Many people find poetry intimidating; humor helps dissolve that fear.

Your essays blend personal reflection with deep respect for tradition, yet they don’t feel academic. Was that intentional?

Very much so. I’m drawn to the personal essay because it allows for reflection, storytelling, and a conversational tone. Academic criticism has its place, but I didn’t want this book to feel like an assignment. I wanted it to speak to poets, casual readers, and even those who might feel unsure about poetry.

Poetry is rooted in human experience, so writing about it shouldn’t feel sterile or detached. I wanted these essays to feel alive and welcoming, to show that poetry is something you can meet on your own terms.

When I wrote about Louise Glück’s “Mother and Child,” my response poem, “To My Chinese Daughters,” emerged from a deeply personal place. Several readers have told me that poem affected them more strongly than the essay, which makes sense to me. Poetry often reaches emotional truths more directly than prose.

In your afterword, you write, “These tribute essays and tribute poems are meant to start discussions, not end them.” Can you elaborate?

Poetry is a conversation, not a conclusion. I’m not trying to offer definitive interpretations of these poets. I’m inviting readers into an ongoing dialogue — showing why these writers matter to me and opening the door for readers to discover what they might mean to them.

That’s why the response poems are essential. Prose can contextualize and reflect, but poetry speaks differently — more emotionally, less explanatory. Together, the essays and poems model engagement that’s both intellectual and felt.

Ultimately, this book is an act of love: for poetry, for the poets who shaped me, and for readers willing to join the conversation. If it encourages someone to pick up a book of poems — or to write one of their own — then it has done what I hoped it would do.

Chad Faries is a Yooper with a Ph.D. in creative writing from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His current poetry collection, Amasa Speaker Factory, is available from Modern History Press.