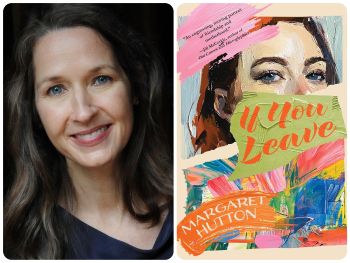

The novelist talks DC, research, and tackling characters’ ethical dilemmas.

Margaret Hutton’s debut novel, If You Leave, moves between the years 1944 and 1973, two eras marked by volatility. The power of the narrative is how it fills out the twilight-zone period in between, when choices are made in secrecy that will resurface decades later. Touching on themes of abandonment, loyalty, and deception, the book is equally a story about motherhood, compassion, and what it means to forgive.

I want to start with how you moved between the 1940s and the 1970s. What drew you to placing them side by side?

While writing If You Leave, I was always thinking about edges and verges as they relate to women. Wartime is a liminal period, and it offers women opportunity for economic independence and new skills. By the end of World War II, they’d had a taste of this but were months away from losing it, which felt rich to explore. At its heart, the novel follows two women without much agency.

[The year] 1973 came naturally, too. Some final scenes take place around Nixon’s inauguration, with an Easter egg about the Supreme Court [Roe v. Wade] decision the next day. By then, I’d nearly finished [writing the novel] when Dobbs was decided, which made it feel even more relevant. There was also the sociological shift in treating unwed mothers. In the early 20th century, service organizations aimed to keep single mothers with their children. By the late ‘40s, those missions had changed, encouraging nearly all mothers to relinquish infants. That trend grew through about 1975. The arc made sense.

You have an ability to render everything visually. What was your research process like, not just to get information but to make it feel so realistic?

I did a lot of research, then tried to forget it so the story wouldn’t sink under the weight. Early sources were David Brinkley’s Washington Goes to War and Steve Vogel’s The Pentagon. A 1951 New Yorker piece about a home for unmarried mothers was helpful. Hunting down details is a seductive trap. For instance, I went to the National Library of Medicine to watch films of a 1930s appendectomy. But I reminded myself this was a character-driven novel, not historical nonfiction. Fiction is about meaning and atmosphere. Still, with the internet, I found myself correcting even bus routes with 1942 maps. I don’t know that it added much, but the lure was strong.

There are a lot of ethical questions your characters face. Did you feel those dilemmas weighing on you as the writer?

That’s why it was important to include both Audrey’s and Lucille’s points of view, even Ben’s briefly. Literature often approaches this from the child’s perspective, since children lack agency. But I wondered: What about adults without agency? The story of the mother who abandons her child has been told, but I was intrigued by the reluctant mother. Audrey is flawed, but she stays and does what she believes is right, even while resisting. There’s no neat resolution.

I also want to ask about the “in-between years,” from 1947 to 1963, which you include late in the book. Why go into them there?

There was a big gap when one character is essentially estranged. I used that section to focus on developments — Audrey’s art career, Lake’s hostility toward her parents. Exploring those years helped me understand the 1973 present.

Speaking of art, you’re a painter. Did that influence your writing?

I started painting only because I thought it would improve my writing. I had no aptitude, but after reading Flannery O’Connor’s essays, I tried it. I liked the process, how it slowed me down, made me more patient, and quieted the constant narrative in my head. I put Audrey at the center as an artist partly out of my own curiosity about what that vision required. Writers often put subjects in their books they want to know more about.

Audrey and Lucille carry choices that define their lives and others’. Do you see them as shaped more by circumstances or their own decisions?

They make decisions, but I hesitate to simplify them as good or bad. Lucille acts, but is it really choice? True choice requires viable, pain-free options, which they don’t have. Audrey has a little more, but she’s boxed in, too. Writing them taught me that when someone feels they have no choice, everyone around them suffers. Pain doesn’t stay with the one who made the “poor decision.” Without intervention, it passes to the next generation.

You set much of the novel in Washington, DC, a city often seen only through politics. How did you approach writing about the city beyond that?

The spark was McLean Gardens, a condominium built to house women recruited for World War II. That drew me to envisioning the domestic. I’ve lived in DC since 1991 [but] never worked in government. For me, it’s personal. As a reporter, I was struck by how staged much of the news was. But behind every government worker is a family drama as heart-wrenching as anywhere else. I was never going to tell a combat story. It was always going to be the home front. That interiority suits a literary novel well.

Hassan Tarek is an arts and culture writer with a focus on historical figures. When not working on long-form profiles, he enjoys learning new languages. He resides in Cairo, Egypt.