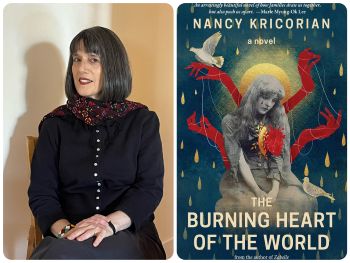

The writer brings stories from across the Armenian diaspora to the page.

The Burning Heart of the World, by New York-based novelist Nancy Kricorian, is a poignant coming-of-age story set largely in an Armenian community in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. In spare language, Kricorian evokes the lasting psychological effects of war and displacement as the novel moves from post-9/11 New York to Lebanon to the Ottoman Empire. In the face of violence and exile, the characters are still deeply human, as Kricorian juxtaposes the quotidian — a school crush, a Halloween costume — with the shocking brutality of war and genocide.

This novel is your fourth in a series about the post-genocide Armenian diaspora experience. What inspired you to set it during the Lebanese Civil War?

When I was in Paris researching my third novel, All The Light There Was, about Armenians who lived through the Nazi occupation, my guide was Hagop, an Armenian who had fled Beirut and moved to France during the Lebanese Civil War. During the day, Hagop took me to visit elderly Armenians, who told me their stories about Paris in the 40s, and in the evening, I went to dinner with Hagop’s friends, who reminisced about their youth in Beirut. They were the children of genocide survivors who had rebuilt their communities in Lebanon, and most of them had grown up in Bourj Hammoud, an Armenian enclave just outside Beirut’s city limits. They had been actors, playwrights, folk singers, and artists active during the flourishing of a new Armenian cultural scene in Beirut in the early 70s. Then the Civil War broke out and set fire to most of what they had built, driving them into exile like their parents before them. Even as I was writing about World War II, I knew my next novel would be about the Armenians of Beirut during the Civil War.

Like your other novels, The Burning Heart of the World is told through the eyes of a young female growing into adulthood and shows how women care for their families through unspeakable violence and exile. Why is this often-overlooked perspective important to you?

When I was in college, I enrolled in a literature seminar that was called “Stages of Modern Self-Consciousness,” and not one book on that syllabus was written by a woman. I asked the professor if I could write a paper about Jane Eyre, one of my favorite novels, which was written by a woman about a woman’s life, and he grudgingly agreed. Later, I took a class on the “Female Bildungsroman,” a feminist examination of women’s coming-of-age novels, a genre that had traditionally been written by and about men. We learned that these stories of the journey from adolescence to adulthood ended differently for women. Rather than arriving at happiness and adult wisdom, as was the case in most of such novels about men, these ones about women often closed with marriage or death. Think of the line in Jane Eyre, “Reader, I married him.” Or the death of Maggie Tulliver at the end of George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss.

I have always been interested in the lives of girls and women and, from my first novel, have chosen to focus on their perspectives and experiences, making formal and thematic experiments within the coming-of-age genre. I have also wanted to show the ways that in times of mass violence and war, women find a way to take care of their families and to survive.

The epigraph quotes musicologist Gomidas’ song “Andouni” — a mournful cry of the homeless, longing for the Armenian homeland. “My heart is like a house in ruins, the beams in splinters, the pillars shaken. Wild birds build their nest where my home once was.” Birds are a recurring motif throughout the book and Armenian folklore. What do they symbolize for you?

Birds have long played an important role in Armenian culture — from folktales to songs and proverbs, as well as in the colophons of illuminated manuscripts. Different species of birds — such as the swallow, the crane, and the stork — have been used to portray varieties of Armenian experience, from suffering and exile to determination and strength. As part of the research for the novel, I started taking bird-watching classes in Central Park to learn more about them, their lifeways, and their intelligence, knowing that they would be threaded throughout the narrative. The novel opens with a young girl witnessing a terrible scene of hunters shooting hundreds of migrating birds from the sky that is a foreshadowing of the Civil War to come. And it closes with a fairytale featuring talking birds that is an homage to the dozens of Armenian folktales that I read while writing it.

This novel ends with the words “For my people.” You’ve dedicated your career to memorializing Armenian stories across the diaspora, from Paris to Boston to Beirut. As an Armenian writer, what responsibility do you feel you carry?

I put those words on the final page of the book in Armenian letters with no translation as a gift and a pledge to my Armenian readers. All four of my novels are part of what I’ve been calling “The Armenian Diaspora Quartet.” This project is a testament to how we carried on over generations and in far-flung communities around the globe in spite of an effort to erase us from the earth and from the annals of history and literature.

Olivia Katrandjian is a writer and journalist published in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Oxford Review of Books, Ms., and elsewhere. Her fiction was listed for Luxembourg’s National Literary Prize, the Bristol and Cambridge Short Story Prizes, the Oxford-BNU Award, and the Dzanc Books Prize for Fiction. She studied creative writing at Oxford University and is the founder of the International Armenian Literary Alliance.