The professor talks New Haven, scary reporting, and telling the story of the Mob.

When I was growing up in West Hartford, Connecticut, my father, an optometrist at the time, always seemed to know when I skipped school.

“My boys saw you driving down Asylum,” he’d say.

I thought he was referring to his gang of fellow eye doctors spotting me and my friends as we headed out of town for a day on the CT shoreline.

It was only years later that I learned he was dilating the pupils of a handful of local mobsters who called him “Doc.” They looked out for him, reporting the whereabouts of his daughter on school days and, sometimes, repaying his services with a freezer full of steaks.

When I handed him Paul Bleakley’s fascinating new book, No Haven: The Connecticut Mob and the Rise of America’s Model City, my dad immediately read the index and told me it was a real walk down memory lane for him.

“Jeez,” he said at one point, “I haven’t thought of Frankie P. in years!”

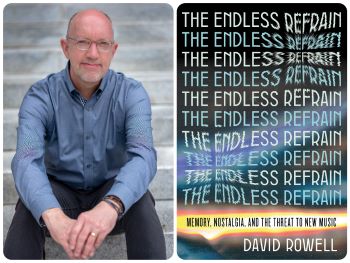

Naturally, I couldn’t wait to talk to Bleakley, an assistant professor of criminal justice at the University of New Haven, about his adopted city’s history of organized crime, the three families that ruled the state through fear and vengeance, and, of course, if a certain Doc had ever entered the narrative.

What does our general fascination with mobsters say about us as a society?

There’s something to be said about the vicarious experience of a risky lifestyle that we wouldn’t experience otherwise. I feel like the “mobster” genre is particularly attractive because we are talking about people who really represent the dichotomy of human nature in some ways. On one hand, we are talking about organized criminals who are prone to violence and do great harm. On the other, we are talking about a group of people who at least purportedly treat each other as “family” and abide by certain rules of conduct. It’s a powerful pull.

Were you aware of the New Haven mob before you moved to Connecticut?

I honestly had no idea about how deep the Mafia story ran in New Haven. I figured that there would be some presence — you couldn’t be located so close to New York without at least some action taking place. I am a reformed journalist, and I always found the best way to start chasing down a story is just to find a place to sit and listen, so I parked up at my local dive bar and just got talking with locals who were born and bred in the area. At some point, one of them casually mentioned a time back in the late 1980s when the FBI found a makeshift mob burial site with several bodies in a garage in a nearby town. It is the kind of thing that gives you whiplash, like, “Did I just hear what I think I heard?” When I went home, I decided to start looking into it and soon went down the rabbit hole.

Did any of the reporting scare you personally?

There is always a concern when you are writing about true crime, and especially organized crime. For me, I think the saving grace is that I am not interested in talking about what people are doing currently…I will leave that to others to write about! I have certainly spoken to a lot of people in the area who have had some connection to the people I write about, but so far, those chats have all been really positive and friendly. Let’s hope it stays that way.

The history of the mob — in Connecticut, as well as in the surrounding states — is Tolstoyesque. How did you keep track of all the affiliations? I imagine your office wall looking like a hunt for a serial killer.

It is funny that you should make that analogy because throughout the writing process, I always joked that the method was a real-life version of the internet meme where the wild-eyed guy has the strings connecting all the notes on a corkboard. When you are telling a dynastic story that spans decades, with multiple crime “families” involved, you have to be able to keep all of your names and places straight. That is made even harder when you have people shifting alliances. That is part of the reason I found it helpful to center the book on three key characters: Midge Renault, Whitey Tropiano, and Billy Grasso. Not only were they the three major forces in the New Haven mob during the timeframe I was interested in, but they also served as representatives of three different crime families who claimed a stake in the city at different times. By focusing in on their stories, I was able to plot out a timeline of their lives, from birth to death, and everything in between. The result was less strings on a board and more like a Venn diagram where people moved in and out of each other’s lives at key points, often disappearing and reappearing in really unexpected ways.

Is there a common personality trait that links criminals throughout history?

There is this concept called soft determinism that I really find myself attracted to. It is the idea that, although we all make our own choices if we are going to take part in certain behaviors like crime, our decisions are all informed — consciously or unconsciously — by the environment we come from and the circumstances we find ourselves in. None of this is to excuse any of the legitimately harmful things that the people I write about did — no question, they were violent people. That said, at the end of the day, people aren’t ever just one thing. These were people who were driven by the same emotions that all of us experience at some point: jealousy, envy, anger, loyalty, respect, even love on some occasions.

[Photo by Taylor Kehoe.]

Cathy Alter is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and the author, most recently, of CRUSH: Writers Reflect on Love, Longing, and the Power of Their First Celebrity Crush.