In his new book, the scholar explores George Washington’s dauntless ambition.

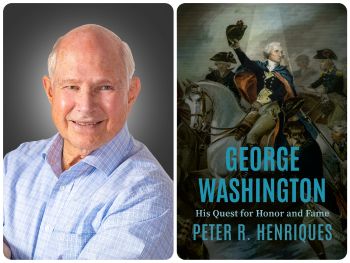

A professor emeritus of history at George Mason University and frequent lecturer on the Founding Era, Peter R. Henriques has written several books and articles about George Washington. His most recent work, George Washington: His Quest for Honor and Fame, published by the University of Virginia Press, was developed from a lecture series Henriques delivered at Colonial Williamsburg.

Your book suggests an intriguing connection between George Washington’s spiritual beliefs, which he tended to be reticent about, and his actions in his public career, which you (and the book’s subtitle) see as a “quest for honor and fame.” What was that connection, and where did you find it?

Washington was reticent about his spiritual beliefs, which has allowed various religious groups to claim him as one of their own. Some Evangelical Christians declare Washington was also a believer — despite the fact that, in his entire private correspondence, he never mentions Jesus even once. That said, Washington believed in a heavenly Providence which intervened in human affairs and in his own life. That belief influenced his actions and what he viewed as virtuous and what was not. Once, while near death as president, he remained preternaturally calm and declared, “I am in the hands of a good Providence.” That said, I posit that Washington was more concerned with secular immortality than the status of his soul. The desire for secular immortality was the most important force determining what he did in crucial moments of his life.

What is your explanation for how a Virginia plantation owner who had prospered immensely under British colonial rule resolved to become a revolutionary intent on overthrowing that regime?

George Washington was a reluctant revolutionary, but he ultimately determined to “devote my life and my fortune” to the cause of resisting British oppression. An intensely ambitious man, Washington found himself treated as a second-class citizen under British rule. He was denied official British rank, hampered in his effort to prosper as a tobacco grower, and thwarted in his dream of a Western empire.

Washington believed that British actions were not only unwise but also were mean-spirited and a genuine threat to his freedom. He wrote to his good friend, Tory-leaning Bryan Fairfax, in 1774, “The crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition that can be heaped upon us; till custom and use, will make us as tame, and abject slaves as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.” Washington much preferred open rebellion to the loss of his freedom. And, just possibly, although he never articulated this goal, he may well have hoped that the glory that was denied him in the French and Indian War could yet be his in this new struggle for freedom and liberty.

Who, among the other leaders of the Revolution and the new republic, would Washington have counted as a friend? And, by your lights, was he a good friend to others?

One might argue that George Washington had a number of “friends” but very few “close friendships.” As he rose to the top of the American world, he was always on stage and on guard, careful not to reveal his inner self. And, of course, relationships changed. In an earlier book, I have a chapter entitled, “Fractured Friendships,” where I examine the break in Washington’s relationship with five famous Virginians — George Mason, Edmond Randolph, James Monroe, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson.

At various times, Washington felt a particular affinity for certain men. He was particularly close to Henry Knox, whom he openly declared he “loved.” His letters to James Madison leading up to the Constitutional Convention reveal Washington’s deep affection for him. He developed a close enough relationship with Gouverneur Morris that allowed the president to warn Morris about certain actions which were viewed as obnoxious by some in Congress. Indeed, the friendship was strong enough that Morris was able to share bawdy jokes with the president. Over time, Washington grew increasingly close to Alexander Hamilton. When Hamilton was ensnared in America’s first great sex scandal, the Maria Reynolds Affair, the president, without making any direct reference to the tawdry affair, sent Hamilton a valuable wine cooler “as a token of my sincere regard and friendship for you.”

In truth, he was not always a good friend. Washington was extremely sensitive to criticism, especially if he thought someone challenged the purity of his intentions. This led him to be unfairly harsh in his dealings with both George Mason and Edmond Randolph.

What qualities allowed Washington to become the pre-eminent leader in a generation of outstandingly talented men?

An essential factor in Washington’s success was his physicality. Roughly 6’ 2” tall, equivalent to 6’ 5” in today’s height, he was powerfully built, a man of absolutely prodigious strength who combined that power with a graceful carriage and majestic walk. In addition to his impressive physicality, he was “awash in talents.” Foremost among them were a keen intelligence, a phenomenal memory, remarkably astute judgment, and, perhaps most importantly, a profound understanding of power and how best to exercise it. He developed and possessed a character that made other men trust him and be willing to make sacrifices for him. He had that unquenchable ambition to achieve honor and fame, and also an indomitable will that made him a formidable adversary. At the core of his being lived a steely will in which gentleness played little part.

As you have noted, it has become impossible to discuss Washington without addressing his lifelong ownership of enslaved persons. When we are considering what of his life story has value in today’s very different world, what are we to make of those decades of apparently unrepentant slaveholding?

Some people, engaging in what I refer to as an “ecstasy of sanctimony,” feel that Washington’s ownership of slaves essentially canceled out any positive things he might have accomplished. After all, they argue, he was a “man stealer.” I am not in the group. When one recognizes that George Washington’s parents, his Bible, his church, his government, [and] his societal leaders all gave sanction to human slavery, it cannot come as a surprise that Washington initially accepted slavery as a fact of life.

It is important to remember that George Washington evolved from a typical Virginia slaveholder to someone who devised a plan to free all the enslaved workers he owned personally. No doubt, he was damaged as a person by what Roger Wilkins has described as “the grating chain of racism and slavery that snaked through the new republic and diminished every life it touched.” Intellectually, he came to see slavery as evil, but he never viscerally felt the evil of the institution. Nevertheless, George Washington’s example of at least partially outgrowing the racist society that produced him can still inspire and encourage.

David O. Stewart is the author of four books on America’s Founding Era, most recently George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father.