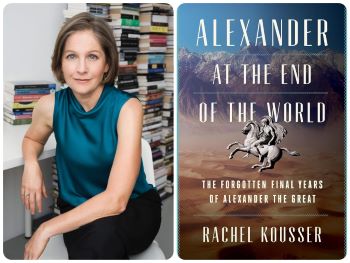

In her latest book, the Classics professor sheds new light on Alexander the Great.

Rachel Kousser’s Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.) is determined to press on until he can’t. While he never reaches the “ocean” (where the world allegedly ends), his swansong seven-year odyssey of brutal campaigning — destroying, building, and rebuilding — covers more than 20,000 miles. As chair of the Classics Program at the Graduate Center, City University of New York and a professor of ancient art and archaeology at Brooklyn College, Kousser brings unique insights about the legendary Greek conqueror to her new book, Alexander at the End of the World: The Final Forgotten Years of Alexander the Great.

In the book, why do you use the word “pathos,” understood here as the desire to possess something you don’t have, in describing Alexander?

When people in the ancient world try to explain why he did things where anybody else would quit, they say it’s his “pathos.” I think he’s often more rational. He wanted to be great. This is why he thought that he was the lineal descendant of Achilles on his mother’s side and Heracles [Hercules] on his father’s.

Alexander takes power after the assassination of his father, Philip II of Macedon. Does he have a personal vision of empire?

He has a vision for what he’d like to try. When he gets it, he’d like to try something more. Early on, he seems fascinated by two things. He brings the Iliad, Aristotle’s copy, along everywhere he goes, and “ocean” is an important character in the Iliad. This plays to Alexander’s great interest in science. How big the world is, what did the end look like? It was like a hypothesis Alexander is trying to prove.

Explain his charismatic appeal to the Macedonians.

This is one of the things that’s hardest to pin down. It’s clear that they would follow him almost in any situation, including situations that were empirically tough. They also recognized he was trained by the best of the previous generation, his father. Also, Alexander could grasp his enemies’ psychology and how to counter what they were doing.

Why first target Persia, the greatest power in the region?

Alexander believed if you’re going to fight, you go up against the best and most financially rewarding.

Although he didn’t capture Persian ruler Darius III, Alexander did take his capital, Persepolis — and, after a few months, sacked it. Why?

Quite early, he starts moving out the treasury. Persepolis, like other major capitals of the Persian Empire, had a huge treasury, two orders of magnitude bigger than any in Greece. He summons all these camels and donkeys [to send] the treasury 300 miles away. That suggests he was planning this from the beginning.

But why destroy the city?

Most classical historians would say he was doing it to impress the Greeks, because they saw this as vengeance for the destruction of Athens 150 years earlier. I would say it’s more aimed at the Persians. They could rally around their king, who was not yet dead.

Yet Alexander mostly maintained the Persian system of administration.

I think he kept enough governors in place and lower-level administrators so [that] if you were a small farmer in Mesopotamia, you wouldn’t necessarily notice there was somebody else in charge.

He also absorbed their specialized warriors into his force and rewarded them with commands.

By the end, he’s got cavalry from Afghanistan because they had the best cavalry. He’s got sailors from Phoenicia and Egypt because they had some of the best navies. He’s got archers from India because they were amazing archers. By the time of his last battle in South Asia, he’s like a conductor in this amazing orchestra. He figured out what each one can do best. When the Macedonians rebel against him, it’s the others, particularly the Persian army, that he goes to. It gives us a sense of the dangers with his multicultural army. It also presents potential payoffs.

Over his last years, Alexander seems less a builder than a destroyer. Is that accurate?

He’s simultaneously a destroyer, a creator, and [a] rebuilder. All three are done strategically. [He] destroys monuments in cities like Persepolis. As builder, he creates this huge tomb [for Hephaistion, his companion since childhood], and there are portraits and other art. Later, you see more rebuilding: the Tomb of Cyrus, the founder of the Persian empire, that had been ransacked, or the Temple in Babylon. He recognizes the chaos and de-civilization that, however unwittingly, he’s unleashed.

The rebuilding shows another side of Alexander regarding religion.

It’s a very different policy from many later empire-builders like Columbus. They come in thinking, “My god is the best and only god.” Alexander absolutely doesn’t do that. He’s much more open to their gods being also powerful. [He’s thinking], “I should make sure that I am trying to work with them.”

“Them” being the cities he founded, you mean?

Alexandria must have been a very small frontier city when he left. Same with Kandahar and Bagram [in Afghanistan]. He is putting into place options for a new form of life in many of these countries. But he dies before most of them have really gotten going. On the other hand, he picks well. Alexandria becomes like Paris in the 19th century. It’s the capital of the Hellenistic world. Kandahar becomes a great city. Many of these places that he shows an interest in do flourish.

Having put aside his quest to reach “the end of the world,” he is suddenly stricken and dies a young man. What happens after that?

Alexander had surrounded himself with men who were extremely capable, extremely ambitious, strongly loyal to him. He was able to give each opportunities to shine. But it was clear that only Alexander was able to make them work together. As soon as he dies, they fought for control of the whole empire; later, it was for whatever they could grab. The result was having Macedonian rulers over vast swaths of the Persian empire. That does last until [their final defeat in] 31 B.C. at the Battle of Actium.

John Grady, a managing editor of Navy Times for more than eight years and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army after 17 years, is the author of Matthew Fontaine Maury: Father of Oceanography, which was nominated for the Library of Virginia’s 2016 nonfiction award. He also has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series and the Civil War Monitor, and he is a blogger for the Navy’s Sesquicentennial of the Civil War site. He continues writing on national security and defense. His later work has appeared on USNI.org, BreakingDefense, Government Executive, govexec.com, and nextgov.com, among other sites.

_Ulf_Andersen.jpg)