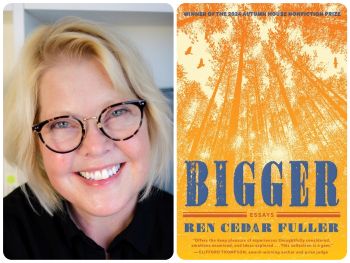

The essayist talks neurodiversity, introspection, and the ethics of lying.

Writer and educator Ren Cedar Fuller has championed diversity throughout her career. Her debut essay collection, Bigger, explores all the ways her family is quirky and how those idiosyncrasies have expanded her world. Fuller’s father was neurodiverse, her child came out as trans, and Alzheimer’s seemed to carry her mother back to her childhood in Ecuador. Fuller’s essays operate from the premise that while some differences aren’t valued by society, our lives can be more joyful because of them.

What inspired you to write Bigger?

Each essay was sparked by a question. The spark for “Naming My Father” came from my sister asking if I remembered a strange thing our dad used to do. For “I Am the Dippy Bird,” it was a question Sonora Jha asked in an online class I took with her: “How does your body move through the world?” I began writing “Eye Contact” after giving a parent-education talk where someone asked, “What does ‘temperament’ mean?”

What is your writing process?

After procrastinating, which is the only way my kitchen gets clean, I finally sit at my laptop. My process begins with that spark I mentioned. I also enjoy research — I loved learning about alligators and aquifers — but each of my essays involved tangents that I ended up cutting. I keep associating ideas until I see a story start to develop. As I revise, I ask, How can I get closer to the story I want to tell?

I like how you question your motives throughout Bigger. Are you a naturally introspective person?

I’m learning, based on feedback from readers, that my ability to question my own ethics without feeling defensive might be unusual. I used to keep track of my mistakes on the whiteboard as an elementary [school] teacher. I wanted the students to know it was okay to make mistakes because that’s how we learn. When the tally marks for my mistakes reached a thousand, I threw the class a “Celebrate mistakes!” party. Now, I just publish my errors as essays.

It’s interesting that you felt you owed acknowledging your mistakes to your students. What do you feel you owe the reader, if anything?

If I’m writing creative nonfiction, I owe the reader my best attempt to discover the truth. As I wrote in “Four Words,” I don’t nitpick: I don’t care if something happened on a Tuesday or Wednesday. But the deeper truths matter, and if I don’t know something, I need to signal (with “perhaps” or “I imagine”) that this is the closest I can come to the truth at this time.

In one of your essays, you admit to lying a lot when you were in college. Did you have any misgivings about putting that in print?

No. I suppose a reader could view me as unethical or as an unreliable narrator, but the essay explores what lying means to me, and in what circumstances I believe it’s acceptable. It describes a childhood when lying was modeled for me by my parents, yet they would have denied their words and actions were a lie. My sisters and I were taught it is always wrong to lie, yet a formative event in our childhood was hearing our mother tell a lie to protect us.

It can be comforting to take an absolutist position about lying. Yet people lie regularly, even the moral absolutists. And we tend to justify our own behavior: “I only lied to protect her feelings.”

Most of us can take a multiple-choice test about ethics and mark the “correct” answers. But life is complex, and sometimes we have to choose between two good things or two bad things. Would you lie to protect your child?

I have no misgivings about writing about my ethical development.

Do you think labeling differences helps?

Every word is a label. Labels can be helpful when they’re viewed as descriptive and understood as a range. If I describe a color as blue, you don’t know which shade I mean, but you know the range of hues. If, as a child, I knew my father was on the autism spectrum and what that meant, many of his behaviors would have made more sense to me. But his experience of autism would have been different from that of every other person with autism.

Labels can be hurtful when they are used to limit people. Fortunately, I see my child Indigo’s generation changing the conversation and owning their labels. They’re neurodiverse and gender diverse and bipolar, and naming their differences allows them to demand the accommodations they need to fully participate in society.

Whose idea was it to offset some of the text in “Four Words”?

The essay describes my upbringing in a fundamentalist Christian home. When I double-checked the wording of a Bible verse online, I accidentally opened a Bible that included commentary. Those texts have the books of the Bible printed in the left column, and a religious scholar’s interpretation of some of the verses in the right column. In my original manuscript, I indented the commentary from the left. My editor, Hattie Fletcher, helped me experiment with layout, and we realized if we also indented the main text — from the right — it would flow better visually for the reader.

We travel with you from Santa Barbara to Seattle to Ecuador. How did you imbue each of these places with such specific local detail?

My family moved about once a year, and my sisters and I remember events by the towns where we lived. I brought geography, history, and culture into an essay if it enhanced the story. While writing “The Tar Rocks,” I remembered how adults in Santa Barbara talked cryptically about the oil spill of 1969. Researching the spill let me feel what those adults must have felt when they saw oil smothering the beaches, and it became part of the story about my coming of age.

Many sections in Bigger end with a lesson, but you never come across as preachy. Does this result from having been a teacher?

I don’t believe people learn complex ideas best through being lectured. For preschool read-alouds, I choose children’s books that are narrative, not didactic. I’m lucky to have writing partners who call out anything verging on condescension in my writing. Preachiness doesn’t work anyway: Whatever I think an essay is about is not what a reader will take from it. I just want to tell a good story.

Amy Roost is the editor of two feminist anthologies, Fury: Women’s Lived Experiences During the Trump Era (Pact Press, 2020) and (Her)oics: Women’s Lived Experiences During the Pandemic (Pact Press, 2021). Roost is currently working on an MFA at Pacific University. She has bylines in multiple publications, including Ms. Magazine, Narratively, Writers Magazine, Dame, Next Avenue, and Publishers Weekly.