The web strategist proves it’s possible to live without your smartphone.

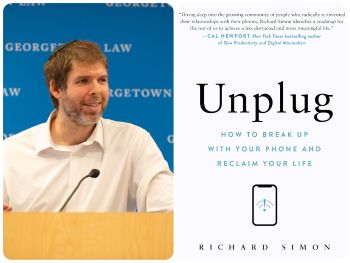

Richard Simon directs website strategy at Georgetown Law, so he’s no technophobe. Yet when he realized that his cellphone was ruling his life, he turned it off…for a year. In his new book, Unplug: How to Break Up With Your Phone and Reclaim Your Life, Simon tells his own story and those of others who’ve made the same decision, and he provides instructions on how to take this radical — but, in his calm and reassuring voice, oh-so-reasonable — step yourself.

When did you first think about turning off your phone?

In 2019, I was a husband and father of two young kids, and the smartphone was putting a strain on so many facets of my life, from my ability to focus at work, to my relationship with my wife, Lauren, to friendships, leisure activities, even being alone with my thoughts. I tried so many different shortcuts — things like a digital sabbath, turning your phone to airplane mode, deleting social-media apps — but they didn’t get me any closer to what I wanted: to be in control of my phone rather than it being in control of me. That’s when I knew I had to do something drastic and decided to turn my smartphone off for an entire year.

How did your family react to your decision?

My wife’s first reaction was a very loving no. She had lots of good questions about how exactly this would work, like what happens if our oldest, who has food allergies, had an anaphylactic reaction and I didn’t have a phone. The compromise I made was that I would not throw my smartphone away. If I took the kids to the aquarium, I would still have my phone, but I just wouldn’t turn it on. Thank God, there were no emergencies, so the phone stayed off for 12 months.

The book is not just your story, but the story of others who’ve turned off their phones for months, years, even forever. What did you learn from their experiences?

When I was first researching the book, I wasn’t sure I’d find anyone who was like me. But I realized that it doesn’t matter what your background is or where you live. This is possible for anyone. I conducted more than 100 interviews. I spoke with a Major League Baseball player, an anesthesiologist, a law partner, a school principal, a software engineer, and many others. I found their stories to be incredibly empowering and inspiring.

When you first gave up your phone, did you have any idea you’d write a book about it?

I wasn’t expecting that a book would come out of it when I began, but after five or six months, I realized that giving up my phone was unbelievably transformative. I was becoming a better version of myself. My wife was seeing it, my kids were seeing it, my dear friends were seeing it. I began to think there was something deeper going on that I could share.

I’m always interested in how people make time to write books, especially when they have a full-time job and a family. Did turning off your phone help?

It definitely helped, but I still had a computer, and there’s plenty of distraction there. What really helped was that I wrote my book almost entirely outside, on the deck of our home in Baltimore, in the freezing cold, at night. I wore a coat and a beanie, and somehow my computer survived. I found that writing outside in the winter and having word-count goals every day was a good formula for me. I knew that if I wanted to get this done, I really had to focus. I knew that if I was in the house, and a kid woke up — at the time, we had three kids under the age of 8 — that would take me right out of my zone.

Your book is a call to action. Since its publication, have you heard stories from others who’ve been inspired by your example?

Yes, I have. One of my favorites was from a minister in rural Mississippi who said he’d been talking from the pulpit about the need to disconnect more from technology, to have a closer [relationship] to God and to his community, and he said that after reading my book, he didn’t just want to talk the talk, he also wanted to walk the walk.

I especially appreciate a point that you made that what the smartphone deprives us of most is time, our most precious resource. Can you talk about that aspect of your book?

As I was going through this process, it was definitely existential in that I was realizing that our time on earth is a finite, nonrenewable resource. The average American spends more than five hours a day on a phone. That’s three months a year that we don’t get back. I’m not anti-smartphone. I still own the same smartphone I had before the detox, but at the end of the day, I want to be able to account for how I used my phone. Giving it up has been like adding more time to my life.

At the end of your book, you talk about life after detox. As you said, you still have a phone, but you don’t use it much, right?

I embrace the same detox strategy, the off-by-default philosophy, but I’ve loosened the definition. After the detox is over and the reward pathways in your brain have been recalibrated, I think you can loosen the definition of off-by-default to only turning on the smartphone if there’s something that you want to do that will enhance your life. When we went to Hershey Park this summer, I plugged in my phone to use the GPS. When we got there, I turned off the GPS, and before we even got out of the car, I turned off my phone, and it stayed off the whole day. Because even after everything that I’ve been through, I know that if the phone was on in my pocket, I’d be half present and half not. But if it’s off, I’m not thinking about it.

Anne Cassidy has been published in many national magazines and newspapers, including the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Christian Science Monitor. She blogs daily at “A Walker in the Suburbs.”