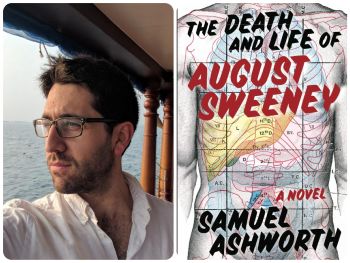

The novelist talks haruspicy, how food mirrors our cultural ambitions, and why cadavers make him hungry.

In his debut novel, The Death and Life of August Sweeney, DC-based writer Samuel Ashworth begins at the end — with the death of his protagonist, a notorious celebrity chef. Dr. Maya Zhu, unaware August Sweeney has hand-selected her to perform his autopsy, pieces together his life by delving into his body. Over the course of a single day, Ashworth weaves the lives of two characters together with an inexhaustible imagination for detail and unflinching humor and irony — nothing is off limits here. The novel explores our appetites for food, pleasure, and fame, and how insatiable hunger can be a barrier to human connection.

The novel uses an autopsy as its framework. How did you arrive at this inventive construction?

The book actually began with that core idea: Could you tell a person’s life story through the dissection of their body? And what if, in telling that body’s story, you could bring it back to life? I had this sense that there is so much life left in the body after death; it all depends on knowing how to look for it.

The question then became, “Well, whose body is it? Whose story are we telling?” A friend in med school took me into her anatomy lab. I walked into the room, and there were 40 cadavers in varying states of dissection. I didn’t know how I was going to react to it — but I especially didn’t expect to get seriously hungry. Like, all-you-can-think-about-is-food hungry. Then my friend told me this was a common reaction for her cohort. That’s when I knew: Whoever this guy on the table was, he had to be a cook. Someone who worked with meat, with bodies, with bone and muscle and fat. And that’s how August Sweeney was born.

As the reader follows August’s career, from dishwasher to celebrity chef, we see how Americans’ relationship to food has changed over the last four decades and how we’ve found new ways to capitalize on hunger. Why were you drawn to this topic?

I believe that food becomes a mirror of our collective cultural ambitions. We aren’t just what we eat, we eat what we are — or, more accurately, what we want to be. The restaurant industry is constantly adapting to the appetites of its client base, which itself is responding to cultural shifts. Part of what the book does is track those shifts in American cuisine over the last 40 years. August’s genius is his ability to adapt to those shifts — usually by shedding his skin — until the day comes when he can’t.

Your attention to detail in this book is remarkable — you fully inhabit your characters in a way that authors like Richard Powers do. You even assisted with autopsies in a Pittsburgh hospital and worked in a Michelin-starred restaurant. How did that research inform the story?

I literally couldn’t have written the book without it. I’d worked in service since I was 16, so I could have capably faked my way through August’s story, but going to work as a prep cook in a French restaurant gave me a far deeper understanding of how great chefs are forged. When it came to the autopsies, though, all I had to go on was what I’d seen on TV, which was laughably wrong. But then I had a stroke of luck: A friend was doing his residency in pathology, and when he did his autopsy rotation, he managed to get permission for me to observe the process for two weeks. I wound up helping out with seven clinical autopsies — these are the kind done in cases of natural, unsuspicious death; the forensic kind is what we see on “Bones” and “CSI.” It was a completely transformative experience because I’d never spent so much time in the company of death — and I found that the more time I spent with it, the less it scared me. That discovery became foundational to the novel, which I feel confident in saying has the power to ease readers’ fear of death.

When the #MeToo Movement reaches the restaurant industry, August must reckon with his behavior. Why did you choose to include this in the book?

I finished the first draft of this book in November 2020, as the culinary and medical worlds were being heaved up by two things: covid and #MeToo. I knew a book that didn’t acknowledge either would be an irrelevance. I also had to admit that as much as I loved August, he wouldn’t have been blameless. So many “great” chefs built their careers on the shattered dreams of others, and August isn’t exempt from that. I wanted to ask what atonement would really look like for someone like him. How can a man like him make amends?

How does Maya, a guarded Chinese immigrant who grew up in the restaurant industry, provide a counterpoint to August’s story?

In the end, the novel is wholly Maya’s, and maybe in my mind, it always was. I like to think that August is why you start reading it, but Maya is why you finish. Maya is the reader, and August is the text. As she says in the book, she’s the haruspex, the diviner of internal organs. She’s the psychopomp, the one who guides mortals into the land of the dead. But she has her own ambitions and needs, too. She’s a young woman in medicine, in an unglamorous, challenging field. She’s the daughter of parents who have always treated the restaurant they run as the favored child. She is obsessed with maintaining her edge by putting up walls against anything that could distract her, and when August enters her life, he lays siege to those walls.

What are you working on now?

I made a sudden pivot to screenwriting a year or so ago, and that’s been terrific. But I actually started the next novel a week or so ago, and the beauty of it is, it’s a lot closer to home than August was. Without giving too much away, it’s about a ghostwriter and the wild west of celebrity memoir.

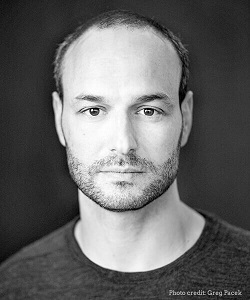

[Photo by Shannon Ding.]

Olivia Katrandjian is a writer and founder of the International Armenian Literary Alliance.