The biographer brings to life a complicated, long-forgotten Marine.

Although a senior Marine Corps officer, Evans Carlson wanted to be buried just like an enlisted man at Arlington National Cemetery. And he was — with the same simple headstone. The lesson he taught his Marine Raiders in World War II was this: The reason we’re fighting this war is to make a better future in the United States. Yet, in 1947, he died utterly disillusioned. According to historian Stephen R. Platt, Carlson’s biographer, “You can’t really understand what he was without understanding all that came before.”

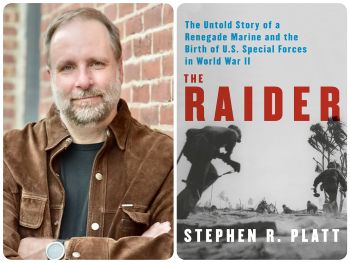

A professor at UMass Amherst whose previous books include Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China’s Last Golden Age and the award-winning Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War, Platt vividly explores Carlson’s contradiction-filled life in The Raider: The Untold Story of a Renegade Marine and the Birth of U.S. Special Forces in World War II.

What did Carlson do after resigning his Army commission following World War I?

He’s a traveling salesman selling canned fruit in Montana. He has a wife whom he barely knows and a baby in California. The restlessness just builds and builds. He leaves his wife. He abandons his son. Carlson comes into the Marines as a buck private. It’s the formative experience of his life.

Years later, after assignments to other stations, China — and its culture, language, and history — seems to provide the college education he never had.

Starting in the 19th century, Westerners were drawn to China by a sense of adventure or opportunity. They threw themselves into trying to understand this vastly different culture with a fantastically different language, with thousands of years of history and characters. Once there, Carlson realizes the Marines have no regular intelligence service in China in 1937, and he can fill that gap. Carlson’s reports, gathered firsthand, are being shared to the upper ranks of the Marine Corps and the Navy. They go to allies. They are talked about at Cabinet meetings [and draw Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s attention]. He establishes himself as the leading Marine Corps interpreter of China. He is a wonderful example of the pre-World War II Marine Corps being remarkably tolerant of quirky, eccentric individuals. Smedley Butler [the Marine Corps major general who wrote War Is a Racket and under whom Carlson served for a time] was a legendary one.

How was Carlson’s thinking about China influenced by Western journalists Edgar Snow and Agnes Smedley?

Snow, who becomes one of his closest friends, is most famous for being the first Western journalist to make it to Yan’an, the capital of the Chinese Communists. He introduces Mao Zedong to the West in what becomes the most famous book on China of the 20th century, Red Star Over China. Though Carlson will make his name as a gung-ho Marine commander, he wanted to be viewed as a literary figure. One of Carlson’s main weaknesses is he really idolized Snow, wished to be him, and wanted a wife like he had.

On the other hand, Agnes Smedley is this leftist radical feminist journalist with a completely outsized personality. At that point, Carlson is a conservative Marine officer, straightlaced, clean-cut. Smedley is a quasi-bisexual libertine. Polar opposites, politically, but they completely fall for each other. I don’t think they actually had an affair, per se, but they become incredibly intense friends for life. Where Carlson and Smedley really connect is in their view of Zhu De, the military commander of the Eighth Route Army but barely known in the West.

Who is Zhu De?

Zhu De is the [military commander] who is going to lead the Communist military forces ultimately to victory in the civil war in the late 1940s. To the Marine, Zhu De is explaining his tactics, explaining fights they had with the KMT [Chinese led by Chiang Kai-shek], explaining how to fight the Japanese. Carlson comes out of these sessions seeing Zhu De as the most unorthodox, effective commander he has ever met or heard of. What Carlson discovered was these Communist fighters were so tightly bound to each other, so incredibly close with their officers. The officers didn’t pull rank. They were respected because they were the best. The incredible willingness for them to suffer hardship, to go on the march with no support, carrying whatever amount of rice they could put in a sack over their shoulder. They have few weapons. Many didn’t have winter coats. Yet they also helped with the planting and harvesting with the poor of the countryside. Carlson witnessed this.

You’re describing “gung-ho.”

Carlson is the guy who gives [the term] gung-ho to the English language. For him, gung-ho meant courageous cooperation in the military unit. It was this interdependence of guerrilla fighters with each other, fighting like a band of brothers. Gung-ho is where the officers are like the fathers and the men are like the sons. Gung-ho is never questioning the risk to yourself and immediately leaping in to help any one of your brothers who needs a hand or who is in danger.

How did Carlson come to lead a Raider battalion?

Largely because of his personal connection to President Roosevelt, he gets command of the unit on the West Coast. Roosevelt’s oldest son, James, becomes his executive officer. Merritt Edson on the East Coast is going to build a unit modeled on the British Commandos and on the rubber-boat raiding tactic that Edson himself experimented with before Pearl Harbor. Carlson is given carte blanche for something never before seen in the U.S. military. He is poaching some of his fellow officers’ best men, getting the best guns, the best equipment. There is no end of resentment from other Marine officers. Especially, he makes enemies with Edson.

What was Carlson’s command philosophy?

As Carlson put it, “We are going to build democracy in this battalion, we are going to fight for democracy abroad, we are going to inspire a democratic awakening in the U.S. military.”

Their first combat experience at Makin Island was a close-run fight, near disaster.

The Second Raiders Battalion were dropped off by two submarines at Makin Island in the Gilberts chain, a few-thousand miles from Pearl Harbor in August 1942. This was a few days after the landing at Guadalcanal. Here are these very young men, many of them teenagers. Their mission is to fire up the engines of their rubber boats, go ashore, and kill all the Japanese. There was a point in the fighting when Carlson is stranded on the beach. The Raiders have lost their weapons in the surf. They have no idea how to get away, no idea how many Japanese are left. The whole thing came within a hair’s breadth of the president’s son getting captured. If the raid, in the end, had enormous propaganda value, think of the propaganda value for the Axis if a Roosevelt had been captured. This mission had nothing to do with Zhu De. In the absolute chaos of trying to get out, nine Marines will be left behind. The Makin Island Raid, in many ways, was an absolute shit show.

What was the media’s depiction of the raid?

The media turn the Raiders into great heroes. They receive a slew of Navy Crosses. But Carlson knows how close this came to disaster. At the end of their next operation on Guadalcanal, he is at the peak of his fame as the original gung-ho Marine. Hollywood produces a movie about him in 1943 called “Gung Ho!” Everything that went wrong in the raid is erased from the movie, and it elevates Carlson as a war hero whose mystique is founded on his experience in China.

What were his tactics on Guadalcanal?

There, they are on a month-long guerrilla patrol behind Japanese lines. They have about 150 Solomon Islander natives who were porters and scouts. They are, in many ways, trying to implement what Carlson learned from Zhu De. Carlson depends on small, extremely tightly-knit fire teams who operate almost as one individual who can separate and regroup with larger forces. His Raiders are extremely mobile. They can’t live off the land in the middle of the jungle. They must have their supplies dropped off for them. They do carry four days of rations; they are cooking rice in their helmets. And they are really suffering physically. But they will come out of this with a kill ratio of something like 30 to one. They will win almost every encounter they have.

After being promoted out of Raider command, he is still driven to be in the fight.

One of the really remarkable sides of Carlson’s personality is his battlefield courage. There is this point in Nicaragua in the 1930s where he has this epiphany. “I now believe in God” [who will shield him in combat]. This is something he will hold to very, very tightly.

How does his experience on Tarawa differ from his time in Raider command?

Carlson volunteers as an observer in the second wave, going ashore with David Shoup, the commander of the forces on the ground. Carlson is going back and forth across the beach and back and forth across the reef to carry information to the ships [on the battle’s progress]. By this point in November 1943, he is 47 years old, he is a World War I veteran, he has got a head of grey hair. But there is nowhere else he wants to be with the world exploding all around him. Carlson has this absolute faith that the bullets are not going to hit him. This is what made him such an absolutely beloved senior officer to enlisted Marines. If this were a novel, the reader would be like, “Yeah, how perfect is that?” But, you know, it happened on Saipan. [He was severely injured.] He went right into the line of fire of a machine gun to pull this poor private out of the way.

After the war, did Carlson have to battle the “Red Menace” label as a public figure — a possible California senate candidate, writer, and lecturer?

He doesn’t live that far into the Red Scare. Shortly before dying, crippled, bedridden, his political career is over. It’s like his mind comes back to China and China becomes his main cause. Carlson’s primary argument is: Chiang Kai-shek cannot beat the Communists. He knows the organizing the Communists have been doing in the countryside for years. His view is the United States needs to let the Chinese figure out their own problems.

What a sad ending to his life.

Carlson comes out of almost 30 years of service to his country and can’t even afford to buy a house. His [third] wife had to get money from Carlson’s friends who pitched in to cover travel costs from Oregon to Arlington National Cemetery. Ultimately, though, the Marines give him — as one of the most decorated Marines of World War II — all the honors at burial. After that, he is thrown into the dustbin of history and stays there.

Has there been any reappraisal of Carlson inside the Marine Corps since?

It is sort of yin and yang. On one hand, he is the original badass. Today’s Marine Special Forces are Raiders again. So Carlson is sort of there in the Marine Corps pantheon. But he is still also generally understood to have been a communist.

John Grady, a managing editor of Navy Times for more than eight years and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army after 17 years, is the author of Matthew Fontaine Maury: Father of Oceanography. He also has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series, Civil War Navy, Sea History, and the Civil War Monitor. He continues writing on national security and defense, primarily for USNI.org.