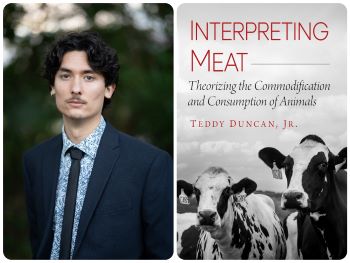

The professor explains why some animals are pets and others are dinner.

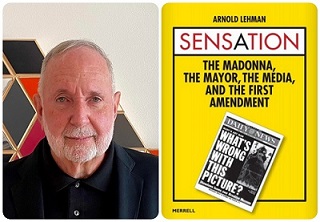

In his debut academic title, Interpreting Meat: Theorizing the Commodification and Consumption of Animals, Teddy Duncan Jr. examines all the ways we distance ourselves from animals — including categorizing some of them as “livestock” — so that we can justify subjugating them. In the book, Duncan, a professor at Valencia College in Florida, also delves into the violence experienced by food animals, as well as the ethical and moral dilemmas surrounding modern meat production.

Though you’ve written several academic articles, Interpreting Meat is your first book. How was the book-writing experience different from what you’ve previously done?

The book emerged from one of those articles, titled “Recognizing Exploitation and Rejecting Analogy: An Analysis of the Meat-Commodity,” which was published in the scholarly journal Between the Species. It would later, in a new, revised form, become the first chapter. The primary difference between writing an article like that and the book was sustaining the continuity of ideas across so many pages. An article normally has a single idea that you’re setting out to articulate (which can already be complicated by sub-ideas); a book consists of a multiplicity of ideas (the chapters and their internal ideas) that need to articulate the larger culminating idea of the book itself. Keeping that in order, and even just recalling previous chapters, was a distinct experience.

Among other things, Interpreting Meat explores the perceived difference between animals and livestock. Can you elaborate?

I detect a specific linguistic function in the term livestock (and I’m certainly not the first, since this is exactly what the term is intended to signify): Livestock are animals rendered “living stock.” This relates to value: “Livestock” designates an animal whose life is reduced to its literal dollar value in the meat-commodity’s production. So, the distinction isn’t between all animals and livestock; livestock are particular animals re-configured through a certain relation to humans.

Here is the true distinction: Those animals who are reduced to value (“livestock” and other animals, such as what I refer to as the “pre-slaughter animal”) and those animals who are viewed as irreducible to their value, who are perceived as a proper “subject.” These designations are largely linguistic. Consider, for instance, a pet conferred a name that individuates them from other animals — the house pet is “valued” in the moral register, while the nameless, non-individuated pre-slaughter livestock animal remains a form of value only in the monetary sense. If you ask someone what their pet is “worth,” they would likely say that, like a human, the pet exceeds any numerical-monetary value. This distinction is complicated further because it is not determined by species: A chicken could be either a pet or poultry, depending on [its] relation to a human.

I’d also like to note that while this has some ethical presuppositions, my analysis catalogs these differences without passing moral-ethical judgment. I try to detail the reality of human-animal relations and our designations of animals in absence of any condemnation.

In writing the book, you consulted everything from Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory to Chick-fil-A ads. What were the challenges in incorporating such vastly disparate materials?

While I mainly relied on academic texts — peer-reviewed journal articles and books — I found it useful to incorporate other, more popular materials. I tried to emulate one of my intellectual heroes, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek, in this approach. Žižek has always explained complex ideas through unorthodox and unexpected, non-academic examples, and I think this leads to a more dynamic (and enjoyable) text. This led to using material, like the Chick-fil-A ads you mentioned, throughout the book. These references aren’t always deliberately pre-planned; sometimes, when writing, you involuntarily link concepts or subjects that appear, on the surface, entirely unrelated.

How did you balance writing the book with your teaching schedule?

It is difficult — but I think conceiving of writing in smaller goal units rather than the totality of the project is very helpful. I had a contract that expected the manuscript by a certain date, but I divided it into smaller segments, like how many words I intended to reach by the end of a given week. Also, I get into a kind of radical excitement about both teaching and researching: Neither of them feels like an unwanted, obligatory activity (aside from certain things, like the process of making an index or sometimes grading). I channel that excitement to work on both my courses and research writing.

Do you have another book project in the works, or is it too soon to ask that question?

While it is currently in its embryonic stage, I am working on a book on Jacques Lacan and animality. In that book, I hope to extend the Lacanian psychoanalytic insights from Interpreting Meat to animals in general: no longer any emphasis on the Marxian-economic side of things or meat production, and instead continuing the hermeneutical “reading” of animals in general using Lacanian thought. In Interpreting Meat, I’m dealing with a cultural object — the meat-commodity. However, in my following project, I am not focusing on an object but rather on animals as living, breathing subjects.

I mention this briefly in the preface, but Interpreting Meat is a book about humans just as much as it is about animals (in a way, mostly about humans), and my next book will focus much more on animals themselves, specifically their subjectivity and unconscious — attempting to answer questions around animal love, language use, and being.

Christina Hawkins, a senior English major at UMBC, recently completed an internship at the Independent.