A roundup of recent poetry from the north.

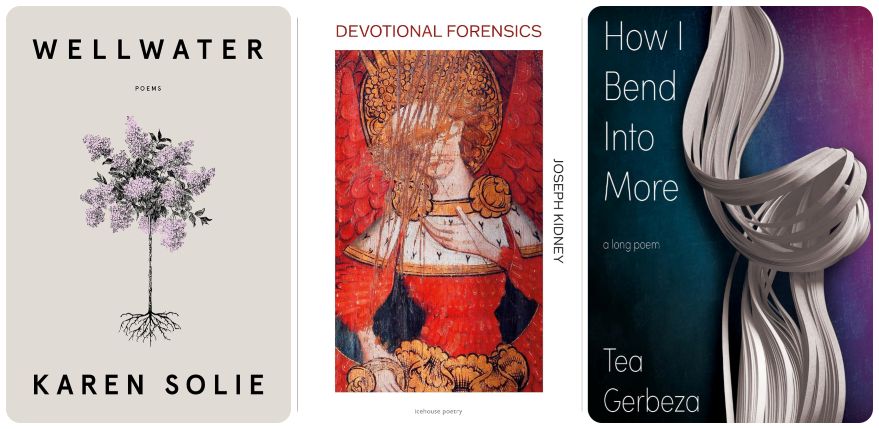

Karen Solie’s Wellwater (House of Anansi Press), her sixth book, doesn’t so much build upon her previous work as continue to draw from the same familiar well. Daniel Fraser, in the Rumpus, rightly recognized that “one of the prevailing tensions” in Solie’s work is “the relationship between nature and human life.”

To refine that observation a little: Solie’s standard technique is to alternate a demotic modernity with natural imagery, the former often represented by digital and consumer technologies, and the latter delivered in an unabashedly Romantic fashion, as if nature is the soul-spring we need (or, given its ongoing despoilation, the ruined version of our souls). This “tension” is a constitutive condition of poetic production in Wellwater, suggesting that a renovation is required in the poet’s vision; tension becomes prescription.

Solie’s technique operationalizes her main subject, which is modern life’s failed escape from the natural world. In Wellwater’s case, that subject manifests as the trendier, through increasingly bourgeois, climate-concerned poetry. Even so, one gets the distinct sense that Solie repeats herself (compare the conceit of Wellwater’s “Red Spring” with “Tractor” from her earlier collection Pigeon). To this reader of contemporary poetry, the subject matter seems oddly behind the times — a lot’s happened since the release of Solie’s 2019 The Caiplie Caves, with countless books appearing in Canada decrying the climate crisis. (For starters, see Madhur Anand’s Parasitic Oscillations and Lori D. Graham’s Fast Commute.)

Further, Solie takes no self-inventory, preferring to write in the abstract about economic conditions without interrogating her own ability to live in Toronto whilst teaching part of the year in Scotland. More evidence of a need for change is the lack of evolution in form. The poems are consistently deenergized by a lack of formal awareness, coming as they do in a standard columnar enjambed fashion that is the Calibri of modern lyric poetry. (In the few cases where there are variations, the difference seems more “alteration,” the same poem merely cut to fit.)

Predictable form and subject create a sameness that merges a single emotional register one might call “overcast.” The sad and mournful poems lack dynamics, sapped of whatever power they might’ve had. The problem Solie has going forward is how to take her considerable talent with interiority-voicing and metaphor-minting and bend it to new pursuits or, barring that, new forms of expression. Perhaps the answer, recalling Fraser, is to create a tension between both.

*****

In Devotional Forensics (Goose Lane Editions), the now Palo Alto-based Joseph Kidney crafts a debut of linguistic ambition reminiscent of the Canadian poetry being published in the late aughts and early 2010s, a corpus that includes Solie. I pinpoint this chronological inception point to contextualize Kidney’s work, not to denigrate it, for Canadian poetry in this moment could use a good deal more purposeful verbal effervescence that seeks to say something, anything, in new ways.

Indeed, the sheer phrasal inventiveness Kidney brings to bear is truly impressive. For example, lines such as, “When I laughed / I felt like my throat was applauding” and “The spark that loosens the power from gasoline. / The smoke that is the tangling of that power” recall the most dextrous offerings from a peak-form Jeramy Dodds.

Also, like Dodds, Kidney compiles explosive lines that don’t quite add up to whole (or wholly lived-in) poems. Unlike Dodds’ peer Solie, whose voicing of interiority immediately connects a reader with the speaker’s consciousness, Kidney prefers to dazzle though abstract, ornate glosses, as if he wishes to demonstrate 55,000 different impressions of 50 different shades of brass in a baroque basilica. Consider:

We send the trash along a progress of soot-lined

chambers, as phenomena were said to pass

through the cells of the medieval brain: grasped

by imagination, sifted through reason, and stored

in memory, a kind of narrowing towards permanence

as if in smallness — from boulder to gravel to sand —

air became the last resort of evidence.

The poet wishes too hard. Precisely dissected qualities (“imagination / reason / memory / narrowing toward permanence as if in smallness / air became the last resort of evidence”) become overweighted, and thereby underdetermined, objects. This habit of abstraction can push the poetry to a comfortable, antiseptic, intellectual distance, making one pine for a more assured use of Solie-esque first-person observation.

That said, the talent on offer here is (have I ever used this word in criticism?) prodigious, suggesting to me that the Louis XIV armchair that is Kidney’s poetry will soon be reupholstered at a Value Village, creating a more lived-in specialness. Even at this date, Kidney deserves favorable comparison to Solie and a further acknowledgement that the sheer thickness, in his work, of religious imagery, history, and practice integrated with contemporary life is vanishingly rare and even more rarely done well.

*****

As is so often true in disability poetics, Tea Gerbeza’s debut, How I Bend Into More, from the disability-friendly Palimpsest Press, showcases form. Gerbeza, who had a wide-angle-curve scoliosis that eventually required surgical intervention and who now lives with chronic pain, begins the single, book-length poem strategically, with a deliberate visual metaphor involving mock corrugations down the center of the page:

|

|

|

|

|

A cut lineA fold line

A stitching

A thread

A surgical trace line

A suture

A scar

|

|

A spine

|

|

|

|

The almost concrete nature of the poem has many valences: It suggests the spine of a body and the spine of a book. There is also the imagery of surgical repair and fraught healing. And yet the poem ends as if the cutting and stitching are ongoing, signifying the enduringness and interruptions of disabled life.

Throughout, Gerbeza constantly varies form while maintaining formal continuity. Many of the fragments adopt quasi to full-on concrete strategies, such as a “glossary of parentheses” that again reflects the divergent spatial orientation of the speaker’s curved body. Other fragments, like “Clearing Up the Question of Why it Takes Me So Long to Get Ready in the Morning,” still pay close but less concrete attention to form by maintaining the “spine” visual metaphor, deploying more regular prosody divided by the central “spine.”

Perhaps the most visually arresting elements of the book are verses that involve paper quilling, moving beyond typography and blank space into a more multimedia ethos speckled with text that interacts poetically with the art — once again visually signaling the interpellation of physical matter inside the “body” of text. How I Bend Into More’s enactment of embodiment, accomplished at a virtuosic level, should make any reader wonder: What will Gerbeza do next?

Shane Neilson is a disabled physician who will publish What to Feel, How to Feel: Lyric Essays on Neurodivergence & Neurofatherhood with Palimpsest Press in June.